There’s this persistent consensual hallucination floating around American boardrooms and think-tank server farms— that empire, the whole blood-soaked apparatus of extraction, coercion, and hegemonic mindfuck, somehow booted up on American soil sometime around 1945, as if the Republic had invented the very wetware of domination. As if Bretton Woods was the Genesis block and everything before was just beta testing.

That’s not a miscalculation. That’s a systems failure of historical memory on an almost neurological scale.

Because here’s the thing about Europe—and I mean the real, sprawling, fragmented, endlessly iterating codebase of Europe, not the tourist-bureau hologram: rerouting around empire isn’t some emergency patch they apply when things get hairy. It’s the kernel. It’s the deep architecture. It’s what they do, the way cephalopods do camouflage or AIs do pattern recognition. They’ve been practicing this dark art since before “Europe” even had a brand identity, back when it was just a chaotic mesh network of warlord-poets and merchant-mystics jacked into Mediterranean trade routes.

From the Middle Ages to the Peace of Westphalia to the European Balance of Power, the continent’s history is essentially a 1400-year-long anti-monopoly algorithm designed to prevent any single “node” (Napoleon, Hitler, Charles V) from achieving total system admin privileges.

Europe doesn’t reroute because it agrees. It reroutes because it doesn’t. Also, rerouting isn’t clean. It has costs—small states crushed, populations traded like assets, moral compromises that would make a bishop weep. A hint of the human “latency” or “data loss” in this constant rerouting might add a layer of grimness.

Rewind the tape. Year 476, Western Rome crashes—hard drive failure, total systems collapse. But watch what happens next: the network doesn’t die, it fragments and routes around the damage. Visigoths here, Franks over there, Byzantium still running legacy Roman code in the East. They’re not building a new universal empire; they’re building a distributed system. Tribal federations, barbarian kingdoms, papal soft power—all jockeying, all hedging, all refusing to let any single node monopolize the bandwidth.

By the Renaissance, the Italians—Venice, Florence, Milan, Genoa—they’ve turned rerouting into high art. City-states treating alliances like financial derivatives: constantly rebalancing portfolios, swapping partners, playing Habsburg against Valois against Ottoman. The balance of power isn’t diplomacy; it’s a protocol. An operating system for preventing monopoly.

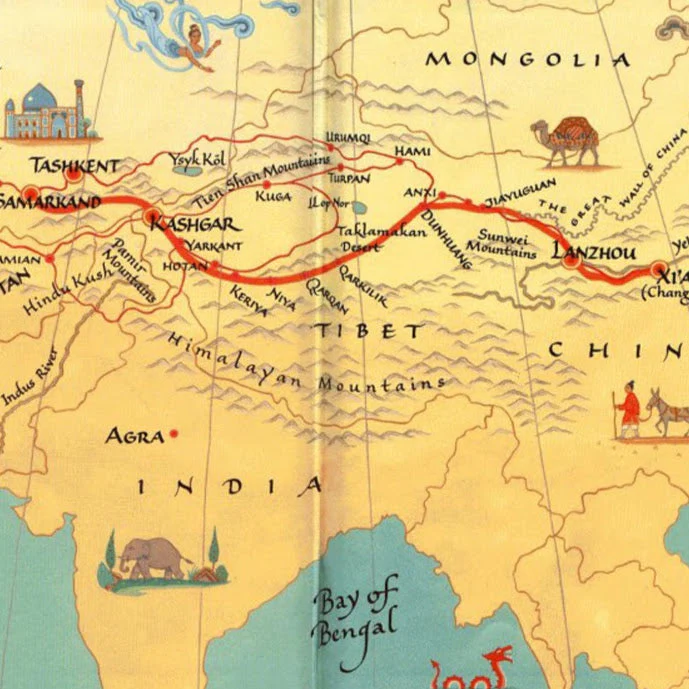

Let’s lock in the baseline assumption once, cleanly, so it doesn’t have to keep hiding between the lines: from Marco Polo to roughly 1800, Europe’s only serious external trade gravity was Asia—and China sat at the center of it. Not the Americas. Not a proto–United States. China.

Fast-forward: Marco Polo trudges back from Khanbaliq in 1295, his head stuffed with visions of Mongol packet-switching and Chinese industrial output. Europe’s trade vectors? Pointing east, across the Silk Road, through Levantine entrepôts, into the perfumed sprawl of Asian markets. For centuries—centuries—the commercial gravity well pulls toward Beijing, not some fever-dream landmass across the Atlantic that doesn’t even have a name yet.

For five hundred years, Europe didn’t trade “globally.” It traded east. China was the manufacturing core, the monetary sink, the civilizational mainframe. Everything else—including the Americas—was middleware.

Then the Portuguese crack the code: reroute around the Venetian-Mamluk monopoly by going around Africa. Da Gama hits Calicut in 1498, and suddenly the Indian Ocean’s a contested network. Spain tries the western route, stumbles into the Americas—happy accident, massive ROI. For a hot minute, Lisbon and Seville think they own the pipes.

But the Americas don’t become an alternative trade partner in this system; they become infrastructure. Sugar as energy. Cotton as fiber. Silver as executable currency. The New World isn’t a rival node—it’s a backend designed to pay Asia.

But the Dutch they’re already running the next exploit. VOC goes live in 1602: the world’s first megacorp, a joint-stock imperial machine purpose-built to reroute around Iberian hegemony. They grab the chokepoints—Malacca, the Cape, Ceylon, the Spice Islands—basically DDoSing the Portuguese into irrelevance. It’s not conquest; it’s hostile takeover.

And the invisible protocol underneath all of this is silver. Potosí boots up in the 1540s, and suddenly the Andes are strip-mined into a planetary liquidity layer. That bullion doesn’t pool in Europe—it tunnels through Seville, crosses the Pacific on the Manila galleons, and terminates in China, which has already standardized silver as money. Europe isn’t dominating the system; it’s routing value through it.

Then the English reroute around the Dutch. Navigation Acts, three Anglo-Dutch wars, the steady corporate imperialism of the East India Company grinding Mughal sovereignty into profit margins. By 1757, Plassey’s in the books and the subcontinent’s a subsidiary.

Meanwhile France is trying to fork the codebase—Quebec, Louisiana, Pondicherry—always hedging, always rerouting around British naval supremacy. And when one power looks too strong—Spain under Charles V, France under Louis XIV or Napoleon—boom: instant coalition. Utrecht, Vienna, the Congress system. Multipolar load-balancing hardcoded into the diplomatic stack.

If you graphed the network instead of telling heroic national stories, it would look brutally simple:

1400 — Venice → Alexandria → Cairo → India → China.

1600 — Amsterdam → Cape → Batavia → China.

1700 — London → Calcutta → Canton.

Different ports. Same destination.

The American Interregnum

So now we get to 1945. The US steps in, all Marshall Plan and Pax Americana and dollar hegemony, and yeah, it looks like empire—because it is, though the branding’s different. “Liberal international order,” they call it. Defensive alliances. Shared values. But scratch the surface and you find the same old imperial sinews: client states, resource extraction, financial chokepoints, the implicit threat of violence underwriting every handshake.

American strategists study empire like a startup case study. Europeans study it like inherited trauma.

Being naturalized gives you the outsider’s clarity and the insider’s heartbreak at the same time. You’re not angry that Americans fail to rule the world well—you’re saddened that they don’t bother to learn it at all, while loudly confusing dominance for understanding. Power is mistaken for perception, reach mistaken for insight.

That confusion is especially tragic because America’s most enduring achievements never came from geopolitical mastery. They came from culture: jazz improvisation, rock’s bastard lineage, film as a dream factory. These were the domains where America didn’t try to be Rome. It riffed. It sampled. It stole shamelessly—and turned theft into style. That’s why it worked.

America’s cultural greatness came, paradoxically, from not understanding the world very well. Jazz didn’t need a theory of empire. Rock and roll didn’t need Bretton Woods. Hollywood didn’t need to “win history.” These forms thrived on provincial intensity, on miscegenation, on accidents and misunderstandings. The ignorance was fertile when it stayed local and artistic. It only became lethal when it went global and strategic.

Europe plays along—partly because the Soviets are scary, partly because American empire is weird. No formal annexation, no governors-general, no viceroys. It’s empire-as-franchise, empire-as-platform. You get the security umbrella, the trade access, the tech transfer—if you follow the house rules.

But here’s where it gets interesting: the minute the hegemon starts acting too imperial—tariffs-as-blackmail, conditional defense, shakedown diplomacy—the old European reflexes light up like a pinball machine. Hedge. Diversify. Reroute.

Europe doesn’t resent American power. It resents monopoly behavior. And when dependency starts getting treated as obedience, the reflex fires.

Suddenly Brussels is talking “strategic autonomy.” Macron’s on the phone to Beijing. Nordstream 2 (RIP) was an attempt to reroute energy dependency around American veto power. The digital euro’s a play to reroute around dollar dominance. Belt and Road looks tempting when Washington’s threatening trade wars.

The Eternal Return

Because empires don’t last. Not Roman, not Mongol, not Spanish, not British, not—spoiler alert—American. What lasts is the rerouting. The hustle. The endless, exhausting, Machiavellian dance of avoiding capture, of keeping multiple options alive, of never, ever putting all your eggs in one hegemon’s basket.

The US didn’t invent this game. It stepped into a game Europeans have been running for two thousand years, a game with rules written in Thucydides and updated through Metternich and Kissinger. And the biggest American mistake—the fatal exception-ism, the arrogance encoded in phrases like “indispensable nation”—is thinking those rules don’t apply anymore, that history ended, that the network topology is fixed.

It’s not. It never was.

Europe’s already rerouting. Not loudly. Not ideologically. But pragmatically, incrementally, the way you survive when empires rise and fall around you like market bubbles. They’ve done this before. They’ll do it again.

The miscalculation isn’t thinking the US is an empire. The miscalculation is thinking it’s the last one, or the only one that matters, or—most foolishly—that it’s somehow immune to the rerouting reflex that’s kept Europe alive, fractured but functional, for longer than America’s even existed. Misreading isn’t an imperial accident; it’s an imperial condition. Power bends epistemology. By the time signals register as resistance rather than noise, you’re no longer sampling reality—you’re sampling compliance, deference, and lagging indicators. Everything arrives late, filtered, delayed, and softened.

Rerouting isn’t a bug. It’s the feature.

And the system’s already compiling the next update.

Leave a Reply