I. The Architecture

In the autumn of 1952, the directors of the National Historical Institute summoned Dr. Eliseo Ferrer to inform him that his services as a chronicler had been terminated. He was not being dismissed, they hastened to clarify, but rather reassigned. After thirty years of distinguished service documenting the agrarian reforms of the previous century, Ferrer had earned what Director Campos called “a position of philosophical importance.”

The Institute no longer required historians in the traditional sense. What it needed now were locators of margins.

“You understand,” Campos explained, consulting a memorandum of impossible length, “that history itself has been completed. The last genuine historical event—the Battle of Pavón, or perhaps the death of Colonel Borgia in the revolution of ’74, accounts differ—occurred long ago. What we experience now are merely footnotes awaiting their proper placement.”

Campos walked Ferrer through the Institute’s new wing, constructed in the International Style, all clean lines and rational proportions. “The convergence architecture. Everything points toward the Resolution.”

The Institute had been revolutionized by Dr. Hermann Weiss, a German exile whose Principles of Historical Teleology had swept through the academy like revelation. Weiss had proven—mathematically, the directors claimed—that all historical events were asymptotic functions approaching a final state. The historian’s task was no longer to observe but to administrate this convergence, filing each occurrence into its appropriate subordinate position.

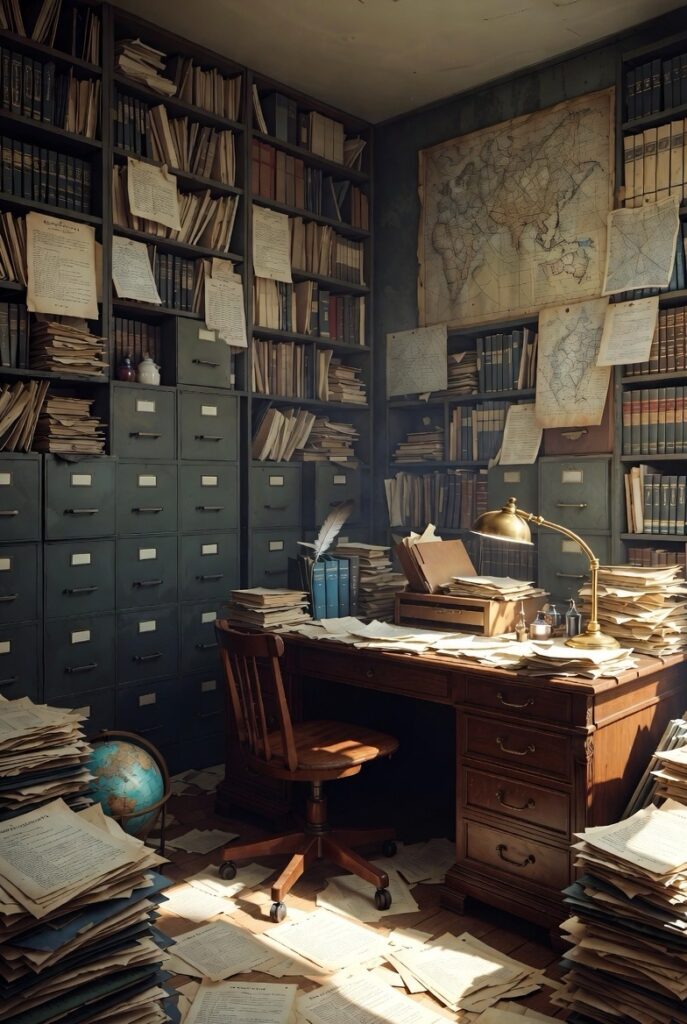

Ferrer accepted the reassignment with the resignation of a man who had spent fifteen years annotating the marginalia of colonial land disputes. His new office was located in the Institute’s sub-basement. They provided him with a massive oak desk, a brass lamp, and the Manual of Historical Classification.

The Manual was a work of staggering ambition, compiled by Weiss and his students over twenty years. All occurrences belonged to one of seven master categories, each representing a stage in history’s convergence toward the Resolution. The Resolution itself was never precisely defined, but the Manual treated this as philosophically sophisticated rather than evasive.

Ferrer’s task was deceptively simple: each morning, he would receive a portfolio of recent events from around the world. His job was to determine where in the vast body of Historical Record each occurrence should be appended as a footnote. The Manual would guide him. The categories would contain him. The architecture would do the rest.

For the first weeks, the work proceeded smoothly. A border dispute in Central Asia: clearly a footnote to the Napoleonic reorganization of territorial sovereignty, Category Three, subsection twelve. A new novel examining the interior life of women: footnote to the Enlightenment’s discovery of subjectivity, Category Five, subsection seven. A workers’ strike in Manchester: footnote to the dialectical resolution of class conflict, Category Six, subsection nineteen.

Each classification felt inevitable once you accepted the premises. The Manual had anticipated everything. Ferrer found this comforting at first—the sense that he was participating in something larger than observation, that he was helping to reveal the pattern that had always been there, waiting.

But in his third week, Ferrer received a report that troubled him. A child had been born in Tucumán who spoke only in questions. Not the ordinary questions of childhood, but philosophical interrogations of disturbing sophistication. At six days old, she had apparently asked her mother: “If I am the subject encountering you as object, what validates your attribution of subjectivity to me?”

Ferrer also received a diplomatic cable from the Foreign Ministry. The Republic of Costa Hueso had vanished.

Not collapsed, not been conquered, not undergone revolution. Vanished. The country had existed on Tuesday—its ambassador had given a luncheon speech at the United Nations—and by Friday it was gone. The territory it had occupied was now dense jungle, uninhabited, with no archaeological evidence of cities or roads. Border nations reported no refugees, no exodus, no military activity. Maps from before Tuesday showed Costa Hueso clearly. Maps printed on Thursday showed only forest, as if the cartographers had never known otherwise.

The only proof of the nation’s existence was documentation: treaties, trade agreements, stamps and currency in museums, photographs of its capital. But these artifacts had become orphaned, pointing to nothing that could be verified. The few hundred Costa Huesans living abroad remembered their country with perfect clarity. No one else seemed to recall it had ever existed.

Ferrer spent four days trying to classify this. The Manual had categories for territorial disputes, for state collapse, for historical revision. But it had no category for retroactive non-existence. Costa Hueso had not ended; it had been edited from continuity, leaving only documentary artifacts like marginalia without a text.

He filed it, finally, under Category Seven: Pending Resolution.

The following week brought something worse. A battle had been fought on the border between Paraguay and Bolivia—the Battle of Chaco Boreal. Both sides claimed victory. This was not unusual. What was unusual was that the battle had been won by both sides simultaneously, in the same location, with neither claim being metaphorical or propagandistic.

Paraguayan records showed 3,000 Bolivian casualties and a decisive territorial gain. Bolivian records showed 3,000 Paraguayan casualties and an identical territorial gain—the same territory. The wounded from both armies were being treated in the same hospitals, in the same beds, occupying them simultaneously without being aware of each other. Journalists from neutral countries who visited the battlefield returned with incompatible photographs: the same ridge held by Paraguayan forces in some images, Bolivian forces in others, both sets of images authenticated, both taken from identical positions at identical times.

The two outcomes had not split into parallel timelines. They existed in the same timeline, superimposed, each one completely real and mutually exclusive.

Category Seven.

That same week, a Thursday occurred twice in San Luis Province. Seven witnesses, none of them known to each other, independently reported living through Thursday the 18th of September twice, with different events transpiring in each iteration. Meteorological records confirmed the anomaly. The sun had risen twice on what should have been a single date.

Category Seven.

Then came reports of a mirror in Buenos Aires that reflected rooms from houses not yet built. A man in Córdoba who remembered his death in precise detail, despite being alive. A street in Rosario that led to different destinations depending on which direction you approached it from.

Category Seven. Category Seven. Category Seven.

Then, in May of 1953, came the reports from Uqbar.

Uqbar was a small nation in Central Asia, previously unremarkable. But over the course of three weeks, every citizen of Uqbar had begun producing a pheromonal compound that induced profound cooperation in human beings exposed to it. The effect was not mind control—subjects retained full autonomy and could choose to leave the affected area. But within proximity to Uqbari citizens, conflict became nearly impossible to sustain. Negotiations that had been deadlocked for years resolved in hours. Ancient ethnic hatreds dissolved into pragmatic cooperation.

The biochemistry was being studied at laboratories in Geneva and Moscow. The compound was real, measurable, replicable in laboratory conditions. What could not be explained was how an entire population had simultaneously begun producing it, or why it had happened in Uqbar specifically, or what evolutionary pressure could have caused such a rapid mutation.

Category Seven.

Within two months, Ferrer’s filing for Category Seven had grown to represent fifteen percent of all events he was asked to classify. The Manual’s introduction had mentioned that Category Seven should comprise “no more than two to three percent” of historical occurrences, and only temporarily, until the convergence process revealed their true positions.

Ferrer raised this discrepancy at the monthly coordinators’ meeting. The other archivists—there were eleven of them, each handling different geographical regions—nodded sympathetically. Category Seven was expanding across all territories. The estimate was now twenty percent global, possibly higher.

The other archivists reported similar patterns. Director Campos showed no concern. “Friction. The Resolution approaches its culmination, and reality resists. Continue filing accurately.”

But Ferrer could no longer pretend he was filing accurately. He was filing incomprehensible events into a category that promised they would eventually become comprehensible.

He began keeping a second ledger. Into this he copied every Category Seven event, but without the official framing. Just the events themselves, described as precisely as the reports allowed.

He titled it The Registry of Orphans.

II. The Divergence

By 1956, the Registry contained three thousand entries. Costa Hueso was not unique—twelve other nations had vanished in similar ways, leaving only documentary traces. The Battle of Chaco Boreal had been followed by seventeen other “superposition conflicts” where mutually exclusive outcomes occupied the same historical space. Uqbar’s pheromonal mutation had spread to three neighboring regions, creating zones where warfare had become physiologically impossible.

The Registry had begun to reveal patterns the Manual could not anticipate. The orphan events were not distributed randomly—they clustered. More than that: they connected. The child who spoke in questions had been visited by the owners of the prophetic mirror. The man who remembered his own death had encountered the Thursday-duplicate, the person who had lived through September 18th twice. These people had begun corresponding, visiting each other, forming what appeared to be a community.

Ferrer called them the Unclassifiables.

They were not deviants or anomalies in the clinical sense. They were simply people around whom reality operated according to logics the Manual could not contain. A woman in Mendoza who existed in two places simultaneously. A teacher in Salta whose students learned entire subjects in single afternoon, then forgot them completely by evening, then relearned them in different configurations. A mechanic who could repair machines by describing their optimal future states, which the machines would then grow toward.

The Unclassifiables had developed their own theories about what was happening. The question-speaking child—now seven years old and calling herself Interrogación, though that was not her birth name—had written a remarkable essay titled “On the Exhaustion of Predetermined Thought.” Ferrer had obtained a copy through the network he was developing.

Her argument was simple: the world had grown too complex for the narrative structures humans used to domesticate it. Frames like the Manual were not describing reality but attempting to anesthetize people to it, offering endpoints that would allow them to stop observing. But reality did not require human permission to exceed human categories. It would continue mutating whether or not the Institute acknowledged it.

“We are not anomalies,” Interrogación wrote. “We are simply the first people the Manual has no words for. There will be more.”

Ferrer no longer attended the coordinators’ meetings. He had requested permission to work exclusively on “Category Seven resolution protocols,” and Campos, pleased to have someone taking initiative, had granted him autonomy.

What Ferrer did not tell Campos was that he had stopped believing in resolution.

The Registry had begun to reveal patterns the Manual could not anticipate. The orphaned nations were clustered temporally—all had disappeared within a fourteen-month window. The superposition battles occurred exclusively in territories that had been sites of previous unresolved conflicts. The pheromonal zones were spreading along trade routes, following patterns of human contact.

These were not random anomalies. They were systematic mutations of historical continuity itself.

Ferrer began corresponding with witnesses. A diplomat who had served in Costa Hueso and now lived in Buenos Aires, carrying his nation’s passport but unable to return to a country that no longer existed. A Paraguayan soldier who had died in the Battle of Chaco Boreal and been buried with full honors, who also had survived and been decorated for valor—the same man, both outcomes equally true, neither negating the other.

A medical researcher from Uqbar who described the change: “One morning I woke and found I could smell cooperation. Not metaphorically—it had a scent, like copper and mint. Everyone around me smelled of it. Within a week, our parliament had resolved thirty years of constitutional deadlock. Not through compromise—through an inability to sustain opposition. The arguments that had seemed vital now seemed incomprehensible.”

These people were not deviants. They were historians, in a sense—living evidence of events the Manual could not accommodate.

The Institute, meanwhile, had calcified into ritualized denial. Category Seven now represented forty-three percent of all global events, but the official quarterly reports listed it at “approximately 4-6 percent, within anticipated parameters.” When Ferrer had pointed out this discrepancy to his immediate supervisor, Dr. Paz, the response had been gentle but firm: “The numbers in the reports are not incorrect, Eliseo. They represent what the numbers will be once the convergence completes. We’re simply anticipating the Resolution.”

This was when Ferrer understood that the Institute was no longer engaged in observation. It was engaged in theology. The Manual had become scripture. The Resolution had become an article of faith. Any evidence that contradicted the faith was reinterpreted as a test of commitment.

He began attending Unclassifiable gatherings. They met in the back room of a café near the docks, and later, when their numbers grew, in a warehouse the mirror-people had acquired. (The mirror-people had become wealthy. Their ability to see future architecture had obvious commercial applications, though they seemed uninterested in profit for its own sake.)

At one gathering, Ferrer met Director Campos.

This should have been impossible. Campos had died seven months earlier—heart failure, sudden but not suspicious. Ferrer had attended the funeral. Yet here was Campos, looking grayer and somehow more translucent, sitting in the corner of the warehouse and drinking mate with an expression of profound relief.

“Eliseo,” Campos said, smiling. “I wondered when you’d arrive.”

“You’re dead.”

“Yes. That’s been filed under Category Seven, I presume?”

Ferrer sat down slowly. “What happened to you?”

“I stopped fitting,” Campos said. “The Manual has no category for directors who lose faith in convergence. For years I felt myself becoming harder to classify, and then one day my heart stopped and I woke up here. Or rather, I kept waking up, in several places, none of them quite where I’d been. The Unclassifiables helped me understand I’d become one of them.”

“The Institute—”

“Is still running on my autopilot,” Campos said. “They haven’t noticed I’m not there. Or perhaps they’ve noticed but filed it under Category Seven.” He laughed, but there was no bitterness in it. “I spent twenty years building that architecture, Eliseo. I believed in Weiss, in the Resolution, in the certainty that history was going somewhere specific and we just had to wait. And then reality started producing forms that made nonsense of all of it, and I had a choice: admit the frame was wrong, or declare reality inadequate.”

“Which did you choose?”

“I tried the second option for years. It almost worked. But there’s a cost to insisting the world must conform to your story about it. Eventually you can’t see what’s actually happening anymore. You just see deviations from what should be happening. I became angry, then exhausted, then brittle. My heart gave out from the effort of maintaining a fiction.”

Interrogación joined them, now twelve years old and carrying an impossible number of books.

III. The Mutation

The café became a regular meeting place. Others arrived: a woman from one of the vanished nations who existed in two places simultaneously. A librarian who could remember books that had never been written, whose memories proved accurate when the books later appeared. A cartographer whose maps showed territories that came into existence only after she drew them.

They called themselves, half-jokingly, the Exceptions.

They were not organizing or advocating. They were trying to understand. And what they understood, gradually, was that the Manual’s categories had begun shaping reality in unexpected ways. By insisting all events must converge toward a Resolution, the Institute had created a tremendous pressure. Events that should have happened but couldn’t be classified had been forced into Category Seven, where they accumulated like water behind a dam.

Now the dam was breaking. History was producing forms that explicitly could not exist within the Manual’s framework—not as mistakes or deviations, but as events that were only possible because they violated the expected categories.

Costa Hueso had vanished because it had been a nation perpetually on the verge of classification but never quite fitting. The Battle of Chaco Boreal had superimposed outcomes because both sides’ narratives were equally valid and the Manual’s insistence on single outcomes had become untenable. Uqbar’s pheromonal mutation had emerged in a region where ethnic conflict had been filed under six different incompatible categories, none of which could account for the actual history.

“We’re not anomalies,” the Uqbari researcher explained. “We’re what happens when reality can no longer fit the shapes we’ve built to contain it.”

The work was exhausting. Without a frame to lean on, every observation required fresh judgment. But Ferrer discovered that abandoning the promise of an endpoint did not lead to paralysis. The opposite: it enabled action.

When the mirror-people’s architecture began spreading into the city’s physical infrastructure—buildings that existed across multiple time states, streets that led to different destinations depending on when you walked them—the Institute’s response was to declare it impossible and wait for it to resolve. They had no conceptual apparatus for structures that violated the Manual’s temporal categories.

Ferrer, frame-light and uncertain, simply asked the mirror-people how their architecture worked. Within a month, he had helped the city government develop provisional building codes. The structures didn’t converge toward anything. They didn’t need to. They simply worked.

This pattern repeated across domains. The Institute couldn’t respond to the Thursday-duplicates’ demand for parallel citizenship because such a thing violated Category Six’s assumptions about political identity. Ferrer helped draft legislation that treated temporal multiplicity as legally recognizable. The Institute couldn’t address the question-speakers’ educational needs because their learning patterns didn’t fit Category Five’s developmental timeline. Ferrer helped establish schools that began with perpetual inquiry rather than predetermined curricula.

Each intervention was provisional, incomplete, open to revision. But each one worked better than the Institute’s insistence that these phenomena would eventually conform to the Manual.

Ferrer brought the Registry to the café. It had grown enormous—seventeen volumes now, meticulous documentation of three thousand events that resisted the Manual’s framework. The Exceptions read through it over weeks, cross-referencing their own experiences.

Patterns emerged. The orphaned nations had all been small states caught between major powers, their existence an inconvenience to prevailing geopolitical narratives. The superposition battles had all occurred in territories that multiple empires claimed as historical destiny. The pheromonal zones had emerged in regions where violence had been normalized to the point where peace had become literally unthinkable within existing frameworks.

These weren’t random mutations. They were corrections—reality finding routes around categories that had become too rigid to accommodate actual complexity.

In 1959, something changed. The Institute published a revised Manual with fourteen categories instead of seven. Category Fourteen was titled “Events Requiring Extended Convergence Periods” and immediately contained sixty-two percent of all classified occurrences.

The Exceptions understood what this meant: the Institute had simply created a larger container for events it couldn’t understand. The architecture remained unchanged. They had not learned.

Ferrer made his decision then. He copied the Registry onto microfilm, delivered it to the Exceptions, and never returned to the Institute.

His supervisor reported his absence as “extended research leave.” His office remained locked. The Institute filed his disappearance under Category Fourteen.

Over the next three years, the Exceptions developed something they hesitated to call a methodology. It was more like a practice of attention. They documented what was actually happening without trying to force it toward a predicted endpoint. They tracked connections between events without needing to know where those connections led.

When new superposition battles occurred, they didn’t try to resolve which outcome was “real.” They documented both, mapped how each outcome affected subsequent events, traced the branches. When new pheromonal zones emerged, they didn’t theorize about evolutionary purpose. They studied the actual mechanisms, interviewed people who lived through the transition, mapped the zones’ growth patterns.

The work was exhausting. Every observation required fresh judgment. But it produced something the Institute could not: useful knowledge.

When the government of Paraguay asked for help negotiating with their quantum military—soldiers who existed in multiple outcome-states simultaneously—the Institute had no framework. They insisted the situation would resolve toward a single timeline. The Exceptions, with no theory of resolution, simply talked to the soldiers, learned how they experienced their multiplicity, and helped draft protocols for simultaneous-outcome governance.

When property disputes arose in former Costa Huesan territory—land that had been deeded by a government that no longer existed—the Institute declared the deeds invalid. The Exceptions helped establish a legal framework that treated documentary evidence as sufficient proof of existence, even for nations that had been retroactively removed from continuity.

When Uqbar’s pheromonal zones began spreading toward conflict regions, the Institute recommended quarantine, fearing contagion. The Exceptions studied the mechanism, discovered it only activated in populations under certain stress conditions, and helped negotiate voluntary exposure protocols. Three long-running wars ended not through defeat or treaty, but through combatants becoming physiologically incapable of sustaining aggression.

Each intervention was provisional. Each one worked.

By 1962, the Registry contained more entries than the Institute’s official Historical Record. The orphaned nations numbered forty-seven. Superposition events occurred monthly. Pheromonal zones covered fourteen percent of the earth’s surface. The Institute’s Category Fourteen had grown to encompass seventy-eight percent of all global events.

The Institute still published quarterly reports insisting the Resolution approached. They had hired statisticians to prove convergence was imminent. They had expanded the Manual to twenty-three categories. They had never once asked the Exceptions what they had learned.

Ferrer was now sixty-four, his hair entirely gray. He spent his days in the café, training younger observers in what he called “description without destination”—the practice of tracking what was assembling without needing to know where it would end.

One evening, a young archivist from the Institute arrived. She carried a folder of recent reports. “Dr. Ferrer? I was told you might help me understand these.”

The folder contained documentation of a new phenomenon: entire cities experiencing different decades simultaneously. Buenos Aires had neighborhoods where it was perpetually 1943, others permanently locked in 1959, still others cycling through multiple years in patterns no one could predict. Residents moved between temporal zones freely but retained the year of their origin zone. A woman born in 1930 might be biologically twenty years old if she’d lived her whole life in a 1943-locked district.

“Category Fourteen?” Ferrer asked.

“Category Twenty-Three now. But they’re all the same, aren’t they? Just different names for ‘we don’t know.’”

Ferrer smiled. “What’s your name?”

“Alicia Soriano.”

“Alicia, the first step is admitting you don’t know. The Institute never takes that step. They rename the category and call it progress.” He opened his Registry. “The second step is paying attention anyway. Come sit. I’ll show you what we’ve learned about temporal inconsistency.”

She stayed until dawn, reading through the Registry, asking questions that had no answers. When she left, she took nothing with her but a method: observe what assembles, track what connects, admit what you cannot predict.

She returned the following week with three other archivists. Then seven. Then twenty.

The Institute still stands, its International Style geometry promising convergence. But in cafés and warehouses throughout the city, historians are learning to work without the promise of Resolution. They track orphaned nations, superposition battles, pheromonal zones, temporal inconsistencies, and a hundred other mutations of historical continuity that the Manual cannot accommodate.

They file their observations under no category whatsoever.

—–

Postscript: The Republic of Costa Hueso was re-discovered in 1964, existing on Tuesdays only. Its government now operates on a one-day-per-week schedule. The Battle of Chaco Boreal’s superposition remains stable; both outcomes continue to be equally true. Uqbar’s pheromonal zones now cover twenty-nine percent of the earth’s surface. The Institute for Historical Classification projects that Category Twenty-Three will decline to manageable levels by 1975, once the Resolution completes. The Exceptions continue their observations.

This account was assembled from Dr. Ferrer’s Registry, verified against available documentation, and left unresolved.

— Archives of Unresolved Observations, compiled 1963

Leave a Reply