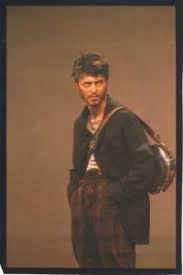

Out here, the air tastes like iron filings and bad liquor. The first shot fired by Bertolt Brecht, a sharp-edged knife in the gut of polite society—Baal, a story about a man too drunk, too damned, and too dangerous to die quietly. The poet Baal is no hero; he’s a gutted animal, dragging his bloated carcass across the countryside, leaving a trail of broken women and shattered faces.

The Germans call it Sturm und Drang, but Baal spits on their labels. Genius? Outcast? Criminal? Doesn’t matter. He’s the reflection in the cracked mirror they pretend isn’t theirs—a fever dream in a society soaked with its own hypocrisy. He loves their scorn, devours their rejection, wears his outsider status like a second skin. The romantics might dress him up as an “inverted idealist,” a blood-stained prophet railing against the world. But Baal? He’s not railing against anything. He’s just tearing it all down because he can.

The nights crawl on, filthy and stinking of sweat. He seduces Johanna, whispers apocalypse into her ear, and watches her sink into the river like a prayer unanswered. Sophie’s belly swells with his seed, but he shrugs and walks away, leaving her to rot under the weight of her shame. And Ekart—poor, stupid Ekart—ends up with a knife in the back for daring to be his friend.

Baal, the drunken prophet of filth and excess, leaves behind not fertile fields but scorched earth. Slavoj Žižek, peering through his cracked spectacles at the corpse, mutters something about ideology in the gutter—Baal as the disjointed symbol of a world that can’t make sense of its own collapse. The anti-hero as the anti-mirror: society sees itself inverted, grotesque, unfiltered, and recoils.

Žižek might say Baal’s story is the ultimate failure of the symbolic order—the bourgeois framework stretched so thin it snaps. Baal doesn’t reject their society; he devours it, leaving them nothing but scraps and bones. He is their repressed truth—desire unhinged, unrestrained by guilt or conscience, the primordial scream of the Real breaking through the surface. The poet as abomination, the genius as wreckage.

The corpses Baal leaves behind—Johanna, Sophie, Ekart—are not just individuals but sacrificial offerings to the hollow gods of modernity. Johanna drowns not because of love, but because of society’s equation of feminine virtue with purity—a virtue Baal gleefully desecrates. Sophie’s pregnancy is a wound inflicted by the same system that abandoned her, while Ekart is Baal’s shadow-self, the weak double whose death marks the poet’s total alienation from the symbolic order.

Baal is the obscene supplement to bourgeois ideology, the truth they refuse to face. He is the collapse of subjectivity, the reminder that we are all, at our core, driven by the same messy, violent desires.

Baal is the god of nothing. A fertility god with no crops to tend, a weather god who brings only drought. A reminder that there is no harvest, no rain, only the rot we plant and cultivate ourselves.

His story is a parody of transcendence, the ultimate joke played on a society still clutching at the idea of moral resolution. There is no redemption, no reckoning—just a slow collapse into filth and silence. Baal doesn’t repent, doesn’t struggle. He simply rots, consumed by the same decay he spread to others.

The forest hut, his final refuge, is no sanctuary but a grotesque monument to the failure of meaning itself. Baal’s life strips away the illusions of virtue and morality, exposing the raw, violent desires that underpin the polished veneer of society.

And that forest hut—Baal’s final scene, where he dies like an animal—is no redemption. It’s a parody of transcendence, the ultimate joke played on a society that still clings to notions of moral resolution. Baal doesn’t repent. He doesn’t even fight. He just collapses, consumed by his own decay.