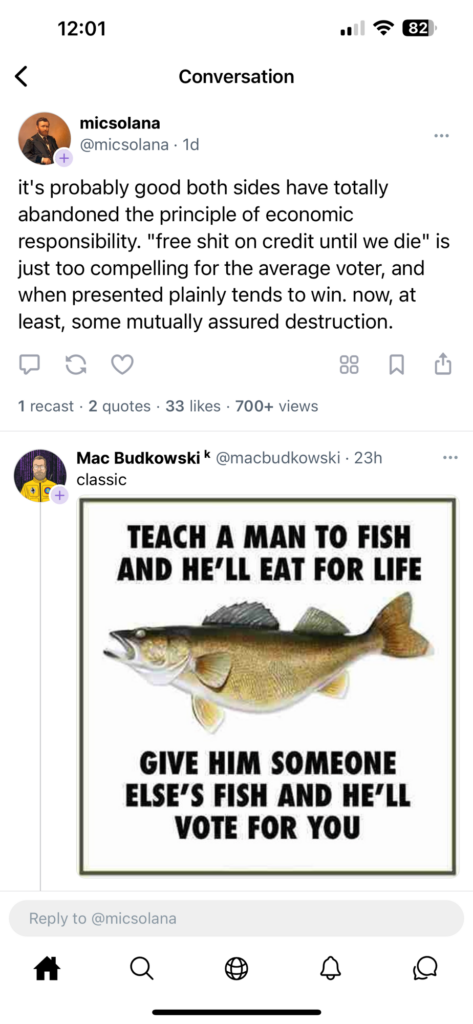

The irony is thick when a Silicon Valley VC criticizes the concept of “free stuff” while the entire tech industry often thrives on giving away services for free, monetizing data, or operating on a “freemium” model. Silicon Valley’s success has largely been built on repurposing industries and offering free or heavily subsidized services to consumers, banking on long-term gains, whether through data, advertising, or eventual market dominance.

It’s a bit like railing against the very system that has allowed their sector to flourish. This comment seems to miss that the “free stuff” model is not just a political phenomenon but a cornerstone of the tech economy. The notion of “mutually assured destruction” might hit closer to home than the VC realizes, given the precarious balance many tech companies maintain between growth and profitability.

Here are more examples of the irony embedded in the VC’s critique:

- Data Monetization: Many Silicon Valley companies offer free services—search engines, social media platforms, and email—in exchange for user data. The “free” model that appeals to consumers is funded by monetizing this data, often in ways that consumers don’t fully understand. Criticizing “free shit” while benefiting from this model highlights a lack of self-awareness.

- Venture Capital Strategy: VCs often invest in startups that operate at a loss for years, prioritizing market share and user growth over profitability. These companies frequently rely on massive infusions of capital to stay afloat, essentially using “free credit” to survive until they can dominate a market or sell out to a larger company. This mirrors the very “free shit on credit” mentality the VC criticizes in the public sphere.

- Freemium Models: The freemium business model, where basic services are offered for free while premium features are charged for, is a staple in the tech industry. This model hooks users with free access and then gradually upsells them, similar to how political promises of “free stuff” can hook voters. It’s ironic that a VC who likely supports companies using this model would criticize similar dynamics in politics.

- Disruption and Devaluation: Silicon Valley is known for “disrupting” traditional industries by undercutting prices or offering services at no cost, often driving competitors out of business. For instance, companies like Uber and Airbnb repurposed transportation and hospitality, respectively, and initially offered services at unsustainably low prices to capture market share. This approach devalues entire sectors, creating the same kind of unsustainable “free for now” dynamic that the VC criticizes in broader economic terms.

- Government Subsidies: Many tech companies benefit indirectly from government subsidies, whether through tax breaks, grants, or other forms of public support for innovation. These subsidies help tech companies thrive, yet the criticism of “free stuff” in the public sector fails to acknowledge how much of Silicon Valley’s success is built on such support.

- Zero-Margin Economies: Companies like Amazon have thrived on razor-thin margins, using their massive scale to undercut competitors and offering free shipping or other perks to consumers. This model is sustainable only because of the vast capital backing these companies, akin to running on “credit.” The irony is in criticizing a similar dynamic in public finance when it’s a standard practice in the industry.

In essence, the VC’s critique overlooks how Silicon Valley has institutionalized “free” in various forms, often relying on delayed or deferred costs much like the “free stuff on credit” he criticizes in politics.

The hypocrisy is palpable. This VC, who likely champions startups built on the very concept of giving things away for free in hopes of monopolizing markets, turns around and bemoans the idea of “free shit on credit” when it comes to public policy. It’s as if he’s blind to the fact that Silicon Valley’s entire playbook is based on the same principle—offering free services, burning through investor money, and banking on some nebulous future profitability.

He decries the “average voter” falling for free handouts while conveniently forgetting that his own success hinges on consumers doing exactly that—lapping up free services while their data is mined, their privacy is eroded, and their choices are funneled into ever-narrowing corridors controlled by tech giants. This is the pot calling the kettle black, only the pot is wearing gold-plated blinders.