“Bad men do bad things in the name of authority”

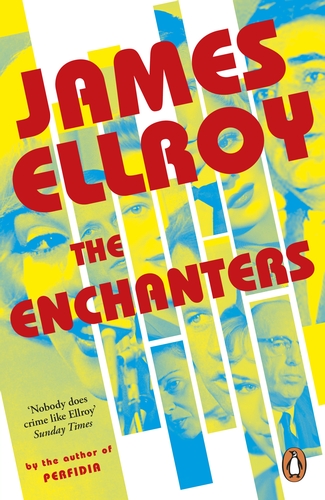

James Ellroy

BAM! Marilyn’s DEAD. The town’s REELING. Camelot’s a CON, and the dream machine’s bleeding out in the gutter. You want TRUTH? You want FILTH? You want the hard, fast, and lowdown LOWDOWN? Step inside, sweetheart. This is The Enchanters.

Freddy Otash—ex-cop, badge-burnt, scandal-slinger, muscle-for-hire. He’s got the DIRT. He’s got the JUICE. He’s got the PUNCH-DRUNK MURDER-LUST and the SHAKES to match. He wants REDEMPTION. But first—he’s gotta wade through the CITY’S SINS.

L.A. 1962: Marilyn took her last breath in a pill-clogged haze. But was it suicide? Was it a shut-up special? JFK, RFK, the REDS, the FEDS—every power player with a pulse is lurking in the margins, greased with guilt, dying to keep the skeletons locked. But Freddy’s got his pry bar. He’s got his hard-on for havoc. And he AIN’T going quietly.

Ellroy’s back, baby. The prose is MACHINE-GUN JITTER. The scandal’s SPLASHY, the corruption’s DEEP, the dames are DOOMED and the bad men BLOOD-DRUNK. This ain’t a book. It’s a SPEEDBALL TO THE CEREBELLUM.

READ IT. LIVE IT. DROWN IN IT.

James Ellroy’s prose is a force of nature—a jagged, propulsive assault of staccato sentences and noir-inflected rhythms that reads like a jazz solo played with a switchblade. His writing in works like The Black Dahlia or American Tabloid is surgically precise, each clause a scalpel cutting into the rot of American institutions. He fractures grammar and chronology with the confidence of a writer who knows rules are only meaningful when shattered with purpose. This style isn’t just aesthetic; it mirrors the fractured morality of his worlds, where chaos and corruption seep through every crack. Yet for all its brilliance, Ellroy’s work hinges on a recurring trope that feels increasingly archaic: the sexually deviant, Oedipal villain who serves as a narrative linchpin, justifying the moral compromises of his antihero cops and G-men.

These antagonists—often reducible to “mother-fixated freaks” or “prostitute-strangling deviants”—strike me as the least compelling facet of Ellroy’s plots. They function less as characters than as ideological boogeymen, reflecting a deeply conservative obsession with sexual transgression as the ultimate evil. In Ellroy’s universe, systemic rot—the military-industrial complex, institutional racism, political conspiracy—is backdrop, while the true horror is always a lone pervert whose deviance (incest, necrophilia, sadism) becomes the moral lightning rod. This framing echoes a reactionary worldview that locates societal collapse not in structures of power but in individual moral decay, particularly sexual “degeneracy.” It’s a sleight of hand: the system (capitalist, patriarchal, white supremacist) is exonerated by scapegoating outliers, as if excising a tumor could cure metastatic cancer.

The cops and feds who pursue these monsters are no heroes, yet Ellroy’s genius lies in making their hypocrisy seductive. They blackmail informants, fabricate evidence, and disappear witnesses—all while waxing poetic about “the greater good.” They collaborate with mobsters to fund black-ops against communists (“traitors!”), profit from drug trafficking while moralizing about “law and order,” and brutalize suspects of color while dismissing civil rights activists as “bleeding hearts.” Their paranoia is selective: they surveil citizens relentlessly but rage at oversight, decry Hollywood liberals as “phony” while pocketing bribes from politicians, and lie pathologically while lambasting journalists as “fake news” avant la lettre. They are, in short, perfect embodiments of authoritarian logic: violence and corruption are permissible, even noble, so long as they serve the “right” side—a side defined by loyalty to the badge, the flag, and a reactionary vision of “traditional” masculinity.

Ellroy’s cops and agents are openly racist, misogynistic, and paranoid, yet they cling to delusions of moral superiority. Their bigotry is worn as a badge of honor, their brutality framed as “hard truths” in a world of “weakness.” This is where Ellroy’s work transcends pulp fiction and becomes a funhouse mirror of American ideology. The real horror isn’t the serial killer; it’s the system that produces—and sanctifies—these “heroic” monsters. The pervert-villain is a narrative copium (

Women as Fetish: The Ultimate Raison d’Être in Ellroy’s Noir

In James Ellroy’s universe, women are not merely characters—they are fetishized objects, spectral forces that haunt the narrative as both motive and metaphor. Their bodies and traumas are the engine of the plot, the raison d’être that overrides all other moral, political, or existential concerns. This fetishization is not incidental; it is the corrosive core of Ellroy’s noir, a lens through which male pathology, systemic authority, and societal rot are refracted. Women exist as catalysts for male action—their violated corpses, their sexualized allure, their idealized innocence—serving as narrative fuel for the obsessive quests of cops, killers, and conspirators. They are reduced to symbols: the Virgin, the Whore, the Victim. But in this reduction, they become the ultimate justification for the violence, corruption, and nihilism that define Ellroy’s world.

The Fetish as Narrative Engine

Ellroy’s male protagonists are driven by a compulsive need to possess, avenge, or destroy women—a need that masquerades as purpose. In The Black Dahlia, Elizabeth Short’s mutilated body becomes an obsession for Bucky Bleichert, not because of who she was, but because of what she represents: a blank screen for male guilt, rage, and voyeurism. Her murder is less a crime to solve than a myth to consume, a grotesque spectacle that allows Bleichert to project his own fractured masculinity onto her corpse. Similarly, in L.A. Confidential, Lynn Bracken—a Veronica Lake lookalike and high-end prostitute—is fetishized as both fantasy and foil, her body a commodity in a marketplace of male desire and power. Women’s trauma is not a subject in itself but a narrative device, a means to propel men into motion. Their suffering is aestheticized, their agency erased; they are MacGuffins with pulse points.

authority as System, Fetish as Distraction

This fetishization serves a dual purpose: it individualizes misogyny while obscuring the systemic structures that enable it. The brutalization of women becomes a personal vendetta (a cop avenging his mother, a killer punishing “sinful” women) rather than a symptom of institutionalized authority. Ellroy’s detectives rage against “deviant” men—the incestuous father, the necrophiliac starlet—while ignoring the complicity of the police, media, and political elites who profit from the exploitation of women’s bodies. The LAPD’s indifference to sex workers’ deaths in L.A. Confidential is not a systemic critique but a backdrop for Ed Exley’s self-righteous crusade. By framing misogyny as the work of lone “monsters,” Ellroy lets the broader culture of toxic masculinity off the hook. The fetishized woman becomes a scapegoat, her body the battleground where male heroes and villains perform their moral theater, all while the machine of authority grinds on.

The Madonna-Whore Dialectic as Conservative Ideology

Ellroy’s women are trapped in a reactionary binary: they are either saints (the dead mother, the virginal victim) or sinners (the femme fatale, the addict). There is no room for complexity, only symbolic utility. This dichotomy mirrors the conservative obsession with female purity—a worldview where women’s value is determined by their adherence to or deviation from patriarchal norms. The fetishization of the Madonna (the idealized victim) justifies male violence as protection; the fetishization of the Whore (the sexualized threat) justifies male violence as punishment. Both positions reinforce male control. Even when women resist—like Grace in White Jazz, who weaponizes her sexuality—their power is illusory, a temporary disruption soon contained by male violence or institutional force.

Ellroy’s Biographical Shadow: Trauma as Fetish

Ellroy’s personal history—the unsolved murder of his mother, Jean—looms over this fetishization like a ghost. Jean’s death, and Ellroy’s lifelong obsession with it, transforms women in his fiction into proxies for his unresolved grief and guilt. The violated mothers and butchered ingenues are not characters but catharsis, a way to ritualize his own trauma through narrative exorcism. Yet this psychological excavation risks reducing real women to symbolic wounds. The fetish becomes a coping mechanism, a way to avoid confronting the mundane misogyny of everyday power structures—the cops who dismiss domestic violence, the media that sensationalizes dead girls—by instead fixating on the grotesque and the taboo.

Contrast with Noir’s Past: Hammett, Chandler, and the Limits of Agency

Unlike Hammett’s Brigid O’Shaughnessy (The Maltese Falcon) or Chandler’s Carmen Sternwood (The Big Sleep), who wield sexuality as a tool of manipulation (however constrained by authority), Ellroy’s women lack even this fractured agency. They are corpses, addicts, or fantasies—never protagonists. Hammett and Chandler, for all their flaws, allowed women to occupy the role of antagonist, complicating the power dynamics of their worlds. Ellroy’s women are inert, their power confined to the gravitational pull they exert on male psyches. The fetishization is totalizing: it consumes the narrative, reducing every interaction to a transaction of control or vengeance.

Ellroy’s Biography as Subtext: Trauma and the Oedipal Obsession

Ellroy’s fixation on sexual deviance cannot be divorced from his personal history—specifically, the unsolved murder of his mother, Jean, when he was 10. Her death haunts his work like a repressed memory, resurfacing in the violated mothers and dismembered women who populate his plots. The Oedipal villain becomes a perverse stand-in for Ellroy’s own unresolved guilt and rage, transforming real trauma into mythic grotesquerie. Yet this psychological excavation risks conflating personal demons with societal ones. The result is a conundrum: while Ellroy exposes the rot of institutions, he displaces collective culpability onto Freudian nightmares, as if societal collapse could be psychoanalyzed away.

Noir as a Mirror: Ellroy vs. His Predecessors

The noir genre has always functioned as a cracked lens through which society’s darkest impulses are magnified, but James Ellroy’s work refracts a fundamentally different vision than that of his forebears, Raymond Chandler and Dashiell Hammett. In Chandler’s The Big Sleep or Hammett’s Red Harvest, the detective—Philip Marlowe, the Continental Op—is a moral outsider, a lone wolf navigating a world poisoned by institutional rot. These protagonists confront systemic corruption: corporate titans who manipulate laws, politicians on the take, police departments bought by mobsters. The detective’s role is that of a disillusioned truth-teller, prying open the lid on a rigged game. Their code, however battered, remains rooted in a cynical idealism: Someone has to care about justice, even if the system doesn’t.

Ellroy’s antiheroes, by contrast, are the system. They are not knights-errant in a trench coat but enforcers embedded in the machinery of power—cops, FBI agents, intelligence operatives. In L.A. Confidential, Bud White and Ed Exley aren’t fighting corruption; they’re weaponizing it. White’s brutal vigilantism and Exley’s calculating ambition are not deviations from the system but expressions of its true nature. Unlike Hammett’s Op, who dismantles a town’s graft in Red Harvest, Ellroy’s characters revel in graft, using it to fund black-ops, silence enemies, and climb hierarchies. The line between cop and criminal isn’t blurred; it’s obliterated. Ellroy’s cops don’t solve crimes—they orchestrate them, framing suspects, fabricating evidence, and collaborating with mobsters to maintain a fragile order. Their moral code, if it exists at all, is tribal: loyalty to the badge, the brotherhood, and the retrograde masculinity that binds them.

Chandler and Hammett’s noir emerged from the Great Depression and postwar disillusionment, framing systemic rot as a betrayal of the American Dream. Their detectives mourn a lost world of honor, however mythic. Ellroy’s noir, born of Cold War paranoia and the collapse of 1960s idealism, rejects the dream entirely. There is no “before” to mourn—the Dream was always a corpse, and the detectives are its grave robbers. Chandler’s Marlowe quips, “I’m a romantic. I hear voices crying in the night and I go see what’s the matter.” Ellroy’s cop snarls, “I hear voices crying in the night, and I make them stop.”

This shift reflects a deeper ideological divergence. Chandler and Hammett critique class and capital: the wealthy patriarch who murders to protect his empire (The Big Sleep), the mining tycoon who enslaves workers (Red Harvest). Ellroy’s villains, however, are psychosexual grotesques—incestuous surgeons, necrophiliac starlets, mother-obsessed bombers—whose deviance distracts from the structural evils enabling them. The systemic corruption (racist policing, CIA drug trafficking, FBI COINTELPRO tactics) becomes background noise, while the narrative fixates on the sexualized “monster.” It’s a bait-and-switch: Chandler’s villains expose the banality of capitalist evil; Ellroy’s villains let the system off the hook by reducing societal collapse to individual pathology.

Stylistically, the contrast is stark. Chandler’s prose is lyrical, steeped in metaphor (“The streets were dark with something more than night”), while Ellroy’s is a jagged, teletype staccato, all hard edges and stripped-down clauses. This isn’t just aesthetic—it’s philosophical. Chandler’s flowing sentences suggest a world where meaning might be uncovered, if one looks deeply enough. Ellroy’s fractured syntax mirrors a world where coherence is a lie, and power is the only truth.

Yet for all his innovation, Ellroy’s focus on sexual deviance as the ultimate sin echoes the reactionary undercurrents of his mid-century settings. By obsessing over “perverts,” his work inadvertently upholds the very moralism it claims to deconstruct. Hammett and Chandler’s detectives fear the rich and powerful; Ellroy’s fear the deviant and diseased. The result is a noir that thrills but rarely indicts—a hall of mirrors where the true horror isn’t the reflection, but who’s holding the glass.