Startup inflation is just the credential inflation of the capitalist hustle culture. If everyone has a degree, it’s worthless. If everyone has a startup, that’s worthless too. We’ve gone from “what school did you go to?” to “what’s your pitch deck?” and the answer is often the same level of vapid. The whole system is less about building value and more about building a persona. It’s positioning, plain and simple.

Low interest rates have bankrolled this circus for years, inflating the importance of entrepreneurial theater. Want to differentiate yourself? Slap together an app that’s just x for [insert industry] or a platform to “revolutionize” something nobody asked to revolutionize. It doesn’t matter if it’s solving anything, as long as positions you. But as soon as rates tick up and the cheap money dries up, we’re starting to see how many of these “visionary founders” are just overqualified bullshit-jobbers in Patagonia vests.

The feedback loop is brutal: you can’t just have a job anymore—you’ve got to be the CEO of something, even if it’s just a half-baked idea running on vibes and angel funding. It’s not cynical to say most startups are worthless. It’s just calling the game for what it is: an overpriced signaling mechanism, dressing up mediocrity as innovation, until the house of cards collapses.

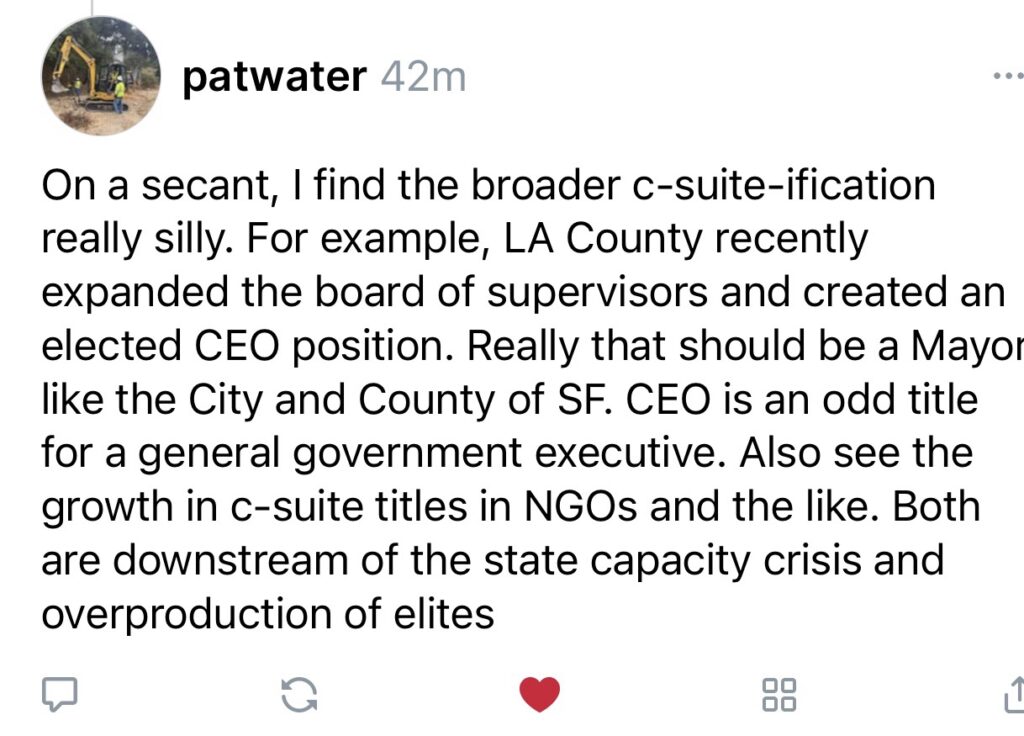

It’s peak managerial theater. As real governing and operational capacity declines, we see these performative structures take root. The titles grow fancier even as the ability to execute declines. Credentialed and non credentialed elites with nowhere to go, invent roles and titles to give the illusion of necessity. C-suite titles in NGOs and local governments aren’t a sign of progress; they’re a symptom of mirroring rot.

Cause let’s not pretend the private sector, propped up by the “best of both worlds”—a steady infusion of free money from artificially low interest rates and an endless buffet of government subsidies, is any better. It survives on the same cocktail of managerial posturing and state-backed largesse, only it’s better at hiding it.

The difference? The private sector doesn’t have to produce results, just valuations. It thrives on hype cycles and cheap cash, masking its dysfunction behind IPOs and PR campaigns. NGOs and government might bloat themselves with meaningless titles, but the private sector takes it a step further: it bloats its entire existence on the fiction of perpetual growth, subsidized failure, and the illusion of innovation.

In short, we’re here because the systems have become self-sustaining feedback loops of mediocrity. They’re all built on short-term gain, hollow metrics, and empty signals. As real productivity and progress have been sidelined, the only thing left is the illusion of action. The result? A world where nothing works, but it looks like it should. Feedback loops reinforce the rot, and everyone is too busy playing their part in the theater of competency to notice the stage is collapsing. It’s not that nobody cares—it’s that nobody dares to admit that the emperor has been naked for decades.

If you think this is bad, just wait until Trump gets back in office and Doge-backed speculators turn the Soviet-style fire sale of state capacity into a meme-fueled casino. Imagine the machinery of government sold off at auction to the highest bidder, except the bids are denominated in shitcoins, and the auctioneer is livestreaming it on TikTok.

The last scraps of state capacity will be repurposed for vibes: national infrastructure rebranded as NFTs, federal agencies spun off as startup incubators, and every last public good turned into a subscription service. It won’t just be bad governance—it’ll be a spectacle of entrepreneurial theater, with a live audience cheering as the scaffolding of the nation comes crashing down.

Think of it as late-stage capitalism with a postmodern twist: a state-capacity yard sale where the winners aren’t even serious players, just grifters who stumbled into power by accident or algorithm. It’s not dystopia; it’s clownworld, but with higher stakes.