Of Empty Armor and Absurd Quests

The first time I read The Nonexistent Knight by Italo Calvino, I imagined I had stumbled onto a lost Monty Python script—one written in secret, translated from the Italian, and perhaps smuggled through time in a hollowed-out codpiece. There it all was: the self-serious knight with no self, the ludicrous battles fought for reasons long forgotten, the crumbling machinery of Church and State, and a narrator who may be inventing the entire tale while cloistered in a convent. If Don Quixote and Waiting for Godot had a baby in a suit of armor, and then handed that baby over to the Pythons for finishing school, this would be the result.

Calvino’s Agilulf is a knight in shining armor—literally only that. He’s a suit of armor animated by sheer will and adherence to knightly protocol, a bureaucrat in a battlefield, a man so perfect he ceases to exist. The knights who surround him are petty, confused, and perpetually distracted. The Church is there to muddle things. Women disguise themselves as men. And all quests lead not to glory, but to farce.

Sound familiar?

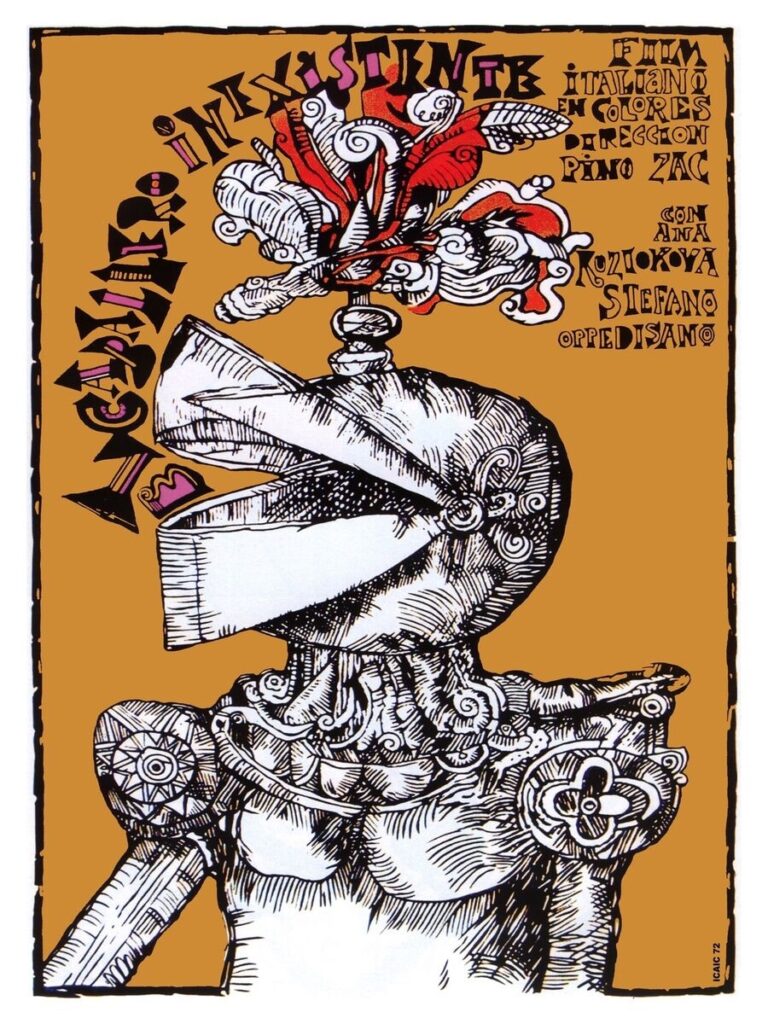

Though there is a 1969 film version of The Nonexistent Knight—a strange hybrid of animation and live-action directed by Pino Zac—it’s worth remembering that Calvino’s novel came first, published in 1962. The film adaptation captures some of the book’s surreal, satirical energy, but it’s the novel itself that feels eerily ahead of its time.

Reading The Nonexistent Knight now, you can’t help but notice how much it seems to anticipate the tone and structure of Monty Python and the Holy Grail (1975). The empty armor, the collapsing logic of knightly codes, the bureaucratization of the quest, the existential jokes delivered in deadpan—Calvino’s book often feels like a conceptual blueprint the Pythons could have stumbled upon, giggled at, and filed away until the coconuts were ready.

it practically is—albeit accidentally, accidentally Italian, and about 70% more philosophical, a dreamlike prequel where the Holy Grail hasn’t been lost yet, the knights are even more neurotic, and God is replaced by bureaucratic absurdity. In other words, imagine this madcap meditation on identity, purpose, and purity… performed by the Monty Python gang.

You’ve got:

A chivalric order reduced to absurd rituals, where no one remembers why they’re fighting but everyone insists on the forms—check.A protagonist defined more by concept than by character (Agilulf as pure will, Arthur as divine appointment)—check.

Knights whose quests collapse into petty squabbles, misunderstandings, or bureaucratic mishaps—check.A narrator who may be making it all up, filtering the story through a lens of religious guilt and romantic confusion—sounds an awful lot like the Holy Grail’s opening intertitles crossed with Terry Gilliam’s God character.

And the kicker: an obsession with the emptiness inside armor—literal in Agilulf’s case, symbolic in the Pythons’.Even the tone overlaps—equal parts high-concept satire, medieval parody, and lowbrow farce.

You could almost imagine The Nonexistent Knight sitting on the same shelf as 1066 and All That or The Goon Show scripts—slotted between Dante and Dada, passed around late-night at Oxford or Cambridge parties.

You’ve got:

A chivalric order reduced to absurd rituals, where no one remembers why they’re fighting but everyone insists on the forms—check.

A protagonist defined more by concept than by character (Agilulf as pure will, Arthur as divine appointment)—check.

Knights whose quests collapse into petty squabbles, misunderstandings, or bureaucratic mishaps—check.

A narrator who may be making it all up, filtering the story through a lens of religious guilt and romantic confusion—sounds an awful lot like the Holy Grail’s opening intertitles crossed with Terry Gilliam’s God character.

And the kicker: an obsession with the emptiness inside armor—literal in Agilulf’s case, symbolic in the Pythons’. Even the tone overlaps—equal parts high-concept satire, medieval parody, and lowbrow farce albeit accidentally, accidentally Italian, and about 70% more philosophical.

If the Pythons didn’t read Calvino, then we’re dealing with one of those eerie creative convergences where the postwar absurdist current broke the surface at the same time in Italy and Britain, each wearing a slightly different helmet.

But imagine, if you will, a dreamlike prequel where the Holy Grail hasn’t been lost yet, the knights are even more neurotic, and God is replaced by bureaucratic absurdity. In other words, imagine this madcap meditation on identity, purpose, and purity… performed by the Monty Python gang.

John Cleese as Agilulf the Nonexistent Knight

Cleese is perfect as Agilulf, the knight so perfect he doesn’t actually exist. With his trademark rigid posture, clipped delivery, and commitment to rules (even when the rules make no sense), Cleese turns Agilulf into a send-up of fascistic order—a man of armor and principle, who literally evaporates if you question him too hard. One can picture him ranting in a tent, correcting everyone’s Latin declensions while polishing armor that may or may not be empty.

Michael Palin as Rambaldo, the Naïve Young Knight

Palin brings his signature wide-eyed innocence to Rambaldo, a character who could wander straight into a shrubbery skit without batting an eyelash. Rambaldo’s quest for glory and love mirrors Palin’s turn as Sir Galahad, always enthusiastic and painfully confused by everything around him. Whether charging into battle or flirting awkwardly with Bradamante, he maintains that classic “Palin-in-peril” charm.

Eric Idle as Torrismund the Monk (Who Might Also Be a Peasant and a Revolutionary)

Let’s slot Idle into this role, shall we? Torrismund, with his secret lineage and shifting loyalties, is ripe for Idle’s gift at playing self-important everymen who talk too much and know too little. Cue a subplot involving mistaken identities, sermons interrupted by peasants complaining about the feudal system, and a song about the joy of not knowing who your father is.

Terry Jones as Bradamante, Warrior Nun and Lovesick Mess

Jones, never one to shy away from playing women, would be perfect as Bradamante, especially in the tragicomic scenes where she pines for Agilulf—yes, the guy who doesn’t exist. His performance would add a delightful awkwardness to Bradamante’s struggle between chaste virtue and frustrated libido, somewhere between Life of Brian’s mother and a lovestruck Valkyrie with a battle axe.

Terry Gilliam as the World Itself (And Probably the Narrator Nun Too)

Gilliam, the animating madman, wouldn’t act so much as warp the entire visual aesthetic of The Nonexistent Knight. Expect forests that look like melting chessboards, siege engines with eyeballs, and paper cutouts of saints wagging fingers. As Sister Theodora, the unreliable narrator who may be inventing the whole story, Gilliam would peer from behind an illuminated manuscript, giggling at inconsistencies and sipping mead from a fish.

David Chapman (a surprise guest star as the Horse)

Let’s get weird and have Chapman play Agilulf’s horse—a beast of burden that, much like its rider, has no actual personality but is imbued with strange dignity. Chapman, master of playing the ultimate straight man in a world gone mad, might even steal the show with a deadpan whinny or a stoic refusal to move in protest of metaphysical contradiction.

The Nonexistent Knight, in Monty Python’s hands, would be less a film than a fever dream of false identities, empty armors, collapsing authority, and slapstick heresy. It’s Holy Grail before there was a grail to lose—where the main joke is that the knightly ideal isn’t dead, but never lived to begin with. A crusade against meaning, carried out by fools, lovers, clerics, and the ghost of reason.

All that’s missing is a shrubbery. And maybe a foot that comes down from the sky and squashes Agilulf into a puff of existential despair.

I mean, the parallels are so specific, it starts to feel less like coincidence and more like a secret adaptation done under the cover of coconut halves.

Honestly, it’s the kind of literary mystery that deserves its own sketch:

Michael Palin: “Look, I told you, Agilulf doesn’t exist!”

John Cleese (in full armor): “Then who’s polishing my pauldrons, you silly man?!”

Terry Jones (as Bradamante): “Does this mean I’ve been flirting with a concept all along?!”

Makes you wonder if Holy Grail was the Pythons’ own answer to Calvino: “What if we took that metaphysical knight… and made him look even more ridiculous?”

In attempting to place The Nonexistent Knight within the world of Monty Python, we inadvertently construct an accidental hyperreality—a blending of Calvino’s medieval archetypes with the absurdity of Python’s comedic sensibilities. By layering these distinct worlds, we’re left with a knight who, while rooted in the medieval tradition, is refracted through the absurdity of modern sensibilities. The Pythons’ characters often embody archetypes of authority, absurd heroism, and misguided purpose—traits that mirror the empty nobility at the heart of Agilulf’s existential crisis. When these elements are layered on top of Calvino’s original medieval constructs, the knightly archetype becomes a hollow, comedic parody of itself. Instead of representing valor and honor, these characters begin to stand for the performance of those ideals, trapped in an endless loop of their own absurdity.

The beauty of this process lies in the accidental nature of it. What begins as an attempt to merge two worlds—the medieval and the absurd—results in a multi-dimensional satire where traditional symbols of knighthood are completely distorted. The knights in Calvino’s narrative are already part of a decaying system, performing a ritualistic role without any true meaning behind it. The Pythons take this idea further, layering on top their own archetypes of bumbling authority figures, smug tricksters, and everyman fools. These characters, often self-important and out of touch with reality, further detach the archetypes of knighthood from any semblance of their original meaning. What we are left with is a hyperreal version of knighthood, one that no longer serves its original purpose but instead reflects the absurd, fractured nature of modern life.

This blending of archetypes—both medieval and Python-esque—creates a simulacrum of knighthood, a copy of a copy, detached from the original context. The more we attempt to analyze these characters, the more they slip away from any grounded reality. They become symbols of symbols, performers of roles that are increasingly irrelevant to the world around them. In a Baudrillardian sense, this is the essence of hyperreality: the collapse of the “real” into an endless chain of representations that no longer refer to any original source. What’s left is a culture where meaning is perpetually shifting, fragmented, and disjointed—a space where archetypes, once fixed and meaningful, have become absurd performances detached from their historical or cultural origins.