So the paradigm exists as I said for the purpose of making sense of your environments so that you can then make meaningful choices and bond reality however paradigms also seem to have two other primary characteristics. The first is the principle of responsiveness which is to say that the paradigm exists as I said for the purpose of making sense of your environments so that you can then make meaningful choices and effective choices in your environment so paradigms emerge so that you can bond reality however paradigms also seem to have two other primary characteristics

The second is the principle of conservation which is to say that paradigms in some sense seek to

change as little as they can possibly change and only change it at the edges minimally

The third is the principle of minimum dissonance which is to say that if some kind of perception shows up some experience comes in that doesn’t make sense in the paradigm. Paradigms need to solve dissonance but they need to resolve dissonance also under the principle of maximum conservation

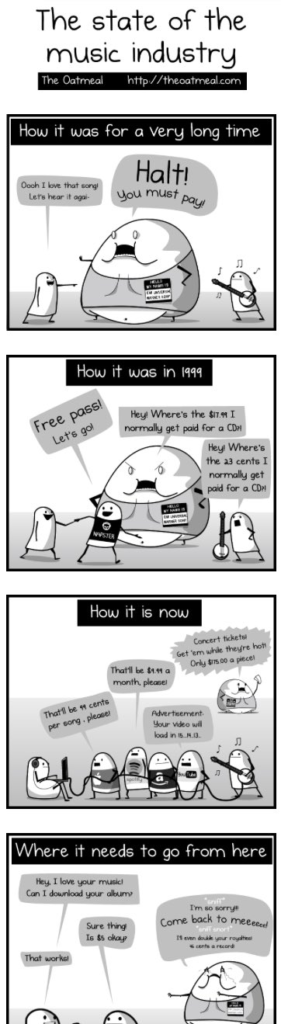

The liminoid experience is a blast however, as their numbers grow, they become a headache. Disciples do all the organizational work, initially just on behalf of liminal mind: out of generosity, and to enjoy a g sub society. They put on events, build websites, tape up publicity fliers, and deal with accountants. The paradigmatic mind just passively soak up the good stuff like Mark Chapman from meaningness highlight — (…) you may even have to push them around the floor; Hipsters they have to be led to the drink. At best you can charge them admission or a subscription fee, but they’ll inevitably argue that this is wrong because capitalism is evil, and also because they forgot their wallet(…)

There’s another phenomenon, that of bro or bro-dude, which is the polar opposite of the hipster. You know them by their preppie-frat-beach-rawk fashions, their polo shirts, their shorts and sandals, their university hoodies, and their backwards baseball caps, You’ve seen them getting way too drunk on weak light beer whenever they’re out,

The paradigmatic mind also dilute the culture. The New Thing, and its liminoid manifestations although attractive, is more intense and weird and complicated than the people stuck in a paradigmatic mind would prefer. Their favorite songs are the ones that are least the New Thing, and more like other, popular things. Some with access to liminal consciousness oblige with less radical, friendlier, simpler creations.

Disciples may be generous, but they signed up to support people that are one step removed from magic able not paradigmatic minds. At this point, they may all quit, and the cultural capital is up for grabs.

“COME IN HERE, DEAR BOY, HAVE A CIGAR

Oh, by the way… which one’s Pink?

The cultural capital at this stage is ripe for exploitation. The liminal consciousness generate cultural capital, i.e. cool. The Disciples generate social capital: a network of relationships — strong ones among the liminal mind, and weaker but numerous ones with paradigmatic mind. The paradigmatic mind, when properly squeezed, produces liquid capital, i.e. money.

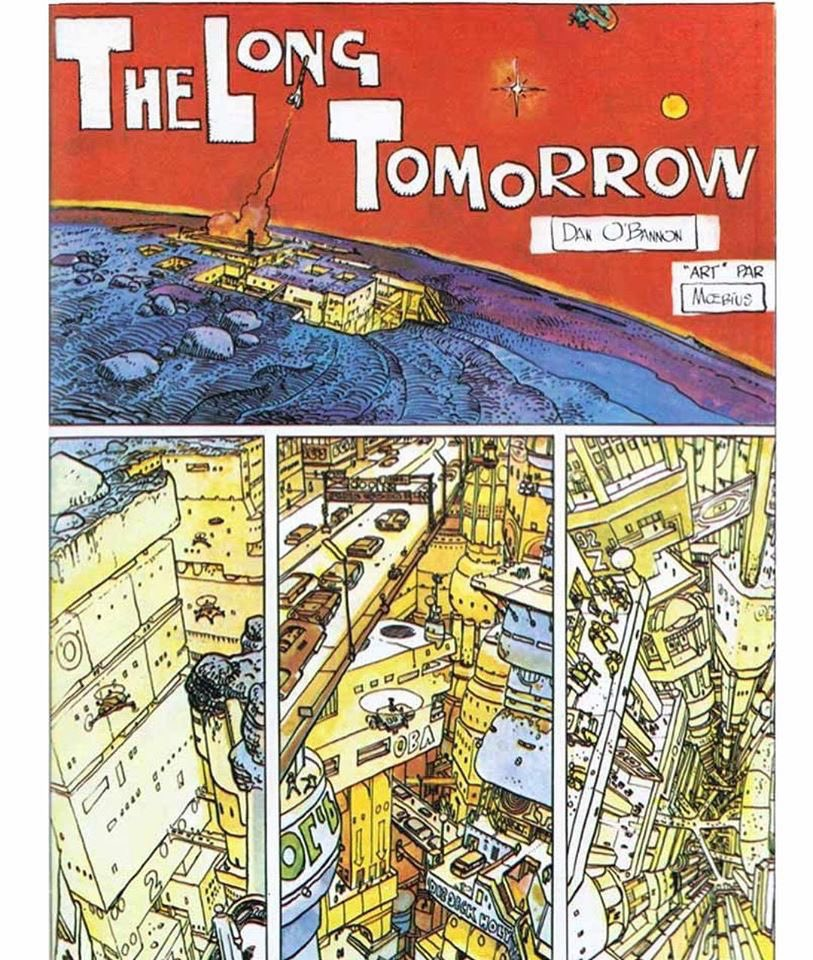

None of those groups have any clue about how to extract and manipulate any of those forms of capital. So the large slug-like sentient species, the Hutts quickly become best friends with people dropping in and out of liminal consciousness. Also at the same time we see the appearance of Doppelgängers. They dress just like the cool, only better. They talk just like the liminal mind — only smoother as if they were partaking of the same liminal consciousness. They may even do some creating/replication — competently, if not creatively. The people dropping in and out of liminal consciousness may not be completely fooled, but they also are clueless about what the hangers on are up to.

People dropping in and out of liminal consciousness really are not much into details and the Doppelgangers look to them like better versions of themselves, only better. They are now the coolest kids in the room, demoting the access to liminal consciousness. At this stage, they take their pick of the best-looking paradigmatic mind to sleep with. They’ve extracted the cultural capital.

The Hutts also work out how to monetize paradigmatic mind — of hipsters and bros which the Disciples were never good at. With better publicity materials, the addition of a light show, and new, more crowd-friendly product, they create a new polished liminoid experience, almost as good as the real thing, admission fees go up tenfold, and paradigmatic mind are willing to pay. Somehow, not much of the money goes to the people dropping in and out of liminal consciousness. However, more of them do get enough to go full-time, which means there’s more product to sell.

The Hutts which have always being in contact with the Empire side also hire some of the Disciples as actual service workers. They resent it, but at least they too get to work full-time on the New Thing, which they still love, even in the Miller Lite version.

As far as the Hutts, Doppelgangers and the empire stormtroopers are concerned, it generates easily-exploited pools of prestige, sex, power, and money.

The rest of the Disciples get pushed out, or leave in disgust, broken-hearted end up hating each other, due first to the stress of supporting paradigmatic mind, and later due to the gangsters crowd divide-and-conquer manipulation tactics.)

THE DEATH OF COOL

After a couple years, the cool is all used up: partly because the shiny New Thing that was was being pushed by the New Kid In Town is no longer new, and partly because it was diluted into New Lite, which is inherently uncool. As the people stuck on paradigmatic minds dwindle, the Hutts and the empire loot whatever value is left, and move on to the next exploit.

They leave behind only wreckage: devastated people on the threshold of awareness who still have no idea what happened to their wonderful New Thing and the wonderful friendships they formed around it.

LIFECYCLES

The Hutts only show up if there’s enough body count of paradigmatic mind to exploit, so excluding (or limiting) paradigmatic mind is a strategy for excluding “Come in here, dear boy, have a cigar” crowds. Some subcultures do understand this, and succeed with it.

So what is to be done? A slogan of Rao’s may point the way: Be slightly evil. Or: The people on the threshold between paradigmatic and liminal consciousness mind need to learn and use some of the “hutt tricks. Then liminal mind can capture more of the value they create (and get better at ejecting bad actors as they arrive.

Rao concludes his analysis by explaining that his Hutts, he calls them sociopaths, are actually nihilists, in much the same sense The cultural capital usually created by people dropping in and out of liminal consciousness is usually eternalistic: the New Thing is a source of meaning that gives everything in life purpose. Eternalistic naïveté makes subcultures much easier to exploit.

“Slightly evil” defense of a cultural capital requires realism: letting go of eternalist hope and faith in imaginary guarantees that the New way pof accessing the liminoid experience will triumph. Such realism is characteristic of nihilism. Nihilism has its own delusions, though. It is worth trying to create beautiful, useful New Things — and worth defending them against nihilism. A fully realistic worldview corrects both eternalistic and nihilistic errors

Liminality