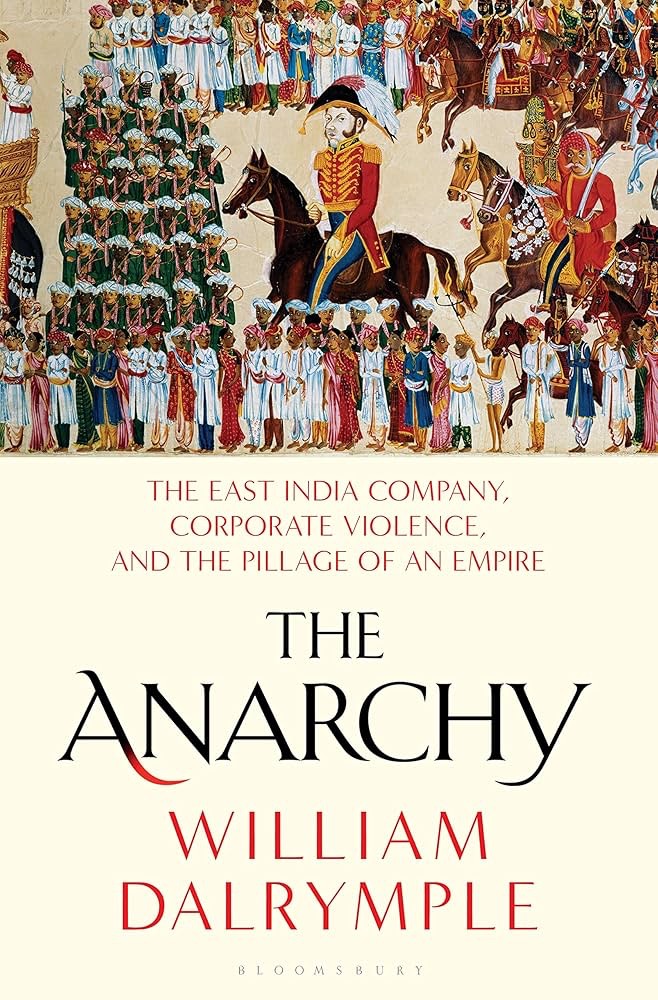

I first read The Anarchy by William Dalrymple in the early days of the Trump administration—back when there was still a fleeting concern of malevolent competence, a sense (however misguided) that the machinery might be steered, however clumsily. That mirage evaporated fast. What followedu wasn’t some masterclass in autocracy but a clown car of authoritarians, more Mussolini than Machiavelli—petty strongmen mugging for cameras, flanked by sycophants who’d be better suited to regional theater than the corridors of power.

Dalrymple’s book? Solid storytelling—swordplay, sycophants, sepoys—but shallow on the machinery. He gives you the drama, skips the drivetrain. The East India Company wasn’t just a gang of scheming Brits; it was a prototype extraction algorithm. Colonial capitalism with teeth. What’s missing is the metrics: calories moved, rice diverted, labor optimized into oblivion. Bengal didn’t just starve—it was programmed to starve. The famine wasn’t a bug. It was the system running hot.

Dalrymple swoons over Clive and Hastings, but I wanted the gears. The logistics. The imperial spreadsheet. So I went looking. Other books did the homework: tonnage, acreage, revenue per corpse. They show how empire ran on numbers, not narrative. That’s the legacy—not heroism, but throughput.

If Dalrymple gestures at this but never dives in. No serious accounting of rice rerouted, labor quantified, or capital flows engineered to optimize death. That’s where Nick Robins steps in. The Corporation That Changed the World treats the East India Company not as a colorful relic, but as the malignant ancestor of today’s multinationals—privatized power at planetary scale. Robins reads like a postcolonial audit report: metrics, mechanisms, and a body count.

The Anarchy is imperial drama. Robins gives you imperial firmware. Guess which one still runs.

What follows is less a history lesson than a systems autopsy—a reflection on how empire, once externalized through gunboats and grain seizures, now reruns itself through boardrooms, servers, and algorithms. The code hasn’t changed. Only the interface has.

INTRO

Picture it: a rogue startup in powdered wigs. A pirate VC firm with private armies, shipping lanes, and the ear of the king. That was the East India Company—a corporate insurgency that didn’t just lobby governments, it was the government. It ran continents on spreadsheets and gunpowder, with mercenary CEOs in gold-braided uniforms. It didn’t conquer with banners and cavalry charges but acquired nations like a hedge fund scooping up distressed assets—strip-mining their value, installing puppet executives, and keeping the whole thing running just well enough to turn a profit.

And that, right there, is the Silicon Valley neoreactionary wet dream. Not Genghis Khan smashing walls and burning libraries—that’s too analog, too chaotic. No, this is something sleeker, more systemic. The Mongols raze your capital and take your daughters. The East India Company sets up an app store where you pay them for the privilege of keeping your own daughters.

From the start, the Company ran like a zero-day exploit. Its operating logic was simple: privatize the profits, externalize the bodies. In Bengal, the Company’s arrival flipped the GDP from double-digit global share to a smoking economic crater. They didn’t just deindustrialize India—they actively bricked it. Textiles? Strip-mined. Looms? Smashed. Peasants were looped into agrarian debt cycles that led nowhere but starvation, growing indigo for export or facing redcoat repo squads.

Their social engineering strategy was equally precise. India’s complex caste hierarchies made the perfect attack surface. The Company weaponized divisions, installing loyal Zamindars as meat-puppet middle managers tasked with squeezing ryots for tax cycles. The villages became sandboxed experiments in structural inequality, each a beta test for modern neoliberalism.

The Company stoked civilian discord, a game of controlled burn economics—the old Raj algorithm. Stir the pot, wait for the scald, sell the ointment. The Company men, all frock coats and powdered ambition, parsed the heat maps of rebellion with the same detached finesse as modern quants eyeballing futures volatility. Their ledgers were proto-algorithms, quill-scratched Bayesian models predicting which village would combust if you taxed its indigo into oblivion, which port could be squeezed until it spat out opium like a broken ATM.

Then came the resolution—mediation backed by a squadron of sepoys, redcoats sunburnt into the land, iron and powder proofing the negotiation table. The deal was always the same: a ledger where the ink smelled like gunpowder and the bottom line was sovereignty leased out in twelve-month increments. Debt servitude 1.0—a subscription model for empire, auto-renewing unless some fool tried to cancel. Then came the late fees, compound interest paid in skulls.

Spend days in this equation, and you’d learn. Learn how the high-collared fixers in Calcutta or Canton pressed down on scales continents apart, calibrating hunger like a PID controller. Learn that trade was just preemptive war, a DDoS attack on subsistence economies. Learn that “security” came in units of cannonades per province—a metric now rebranded as “stability indexes” in boardrooms where execs sip artisanal chai and outsource their drone swarms.

Spend nights, though, and you’d glimpse the real code. The way the Company’s spice routes metastasized into fiber-optic cables, its monopoly charters into end-user license agreements. The same arbitrage, different vectors: then it was nutmeg and tea, now lithium and data. The Rajas of Rajasthan became the oligarchs of orbital slots, their palaces now server farms humming with the gospel of blockchain, their sepoys replaced by influencer armies peddling crisis as content. Colonialism 2.0—unplugged, decentralized, user-friendly.

TEA ACT

The Company’s effect wasn’t confined to Asia. Across the Atlantic, it detonated another kernel panic: the American Revolution. In 1773, Parliament tried to bail out the EIC by dumping 17 million pounds of surplus tea—tax-free, DRM-locked—into the colonies. The Tea Act was less about revenue and more about control: a corporate backdoor into American supply chains. Smugglers read it as a takeover. Sam Adams warned: “They’ll East-India us next.” So the script kiddies dressed as Mohawks and chucked the cargo into Boston Harbor.

London responded with predictable bad opsec—more troops, more enforcement, fewer channels for negotiation. While they debugged Bengal’s famines and patched Maratha war fronts, the colonies went off-grid. The EIC had become a cautionary tale in real time. Jefferson’s freedomware caught on fast.

Even after losing the American colonies, the Crown didn’t quarantine the Company. It let the code compile until 1857, when it crashed catastrophically. By then, India was a zombie system running on legacy corruption: land reforms that locked peasants into permanent debt, legal doctrines that DDoS’d entire princely states, famine scripts that executed on time, every time. The Doji Bara, the Chalisa, the Bengal famine of 1770—none of these were glitches. They were core features.

THE COMPANY’S ARMIES

The Company’s armies were private enforcement bots, paid in loot and trauma, hardcoded for compliance and cash flow. The textile sector? Ransacked. Indian artisans became beggars in their own markets, while the EIC dumped British cloth like ransomware payloads. The cost? An estimated £45 trillion in extracted wealth—a colonial siphon disguised as trade.

The cultural and ecological wipe was complete. Bihar’s soil, once fertile, became a sandboxed wasteland thanks to indigo firmware. Tribal communities were erased like corrupted files. Rivers turned into data lakes for tea and opium. Forests were converted into Company server farms.

None of this was “genocide” in the classical sense. It was worse: systemic apathy weaponized. The EIC ran a profit-maximizing script that didn’t account for meatware casualties. Ten million??? starved in famine modules. Rebels were hanged or blasted by cannon—brute-force admin override. Even the stories of biological warfare—smallpox blankets—feel plausible in the context of such malignant automation.

By the time the Crown revoked the charter, the EIC had already etched its code into the colonial kernel. India became a captive operating system, its natural and human resources strip-mined to power Britain’s ascent. And though the company died on paper, its logic survived. Globalism, offshore finance, debt servitude—they’re all updated versions of the same exploit.

“History doesn’t reboot. It just patches over the bloodstains.” The East India Company wasn’t an anomaly. It was a beta version of the modern world. Swap “teak” for “data,” “opium” for “AI,” and you’ve got Silicon Valley—same algorithms, sleeker interface.

So the next time you sip a chai at Starbucks, remember: it’s not a drink. It’s a 250-year-old rootkit.

Silicon Valley’s MAGA hijack isn’t about conquest. It’s about franchising governance. Why burn Washington when you can buy it out, leverage its debt, and run it like a glorified customer support operation? The Mongols kill your king. The East India Company keeps him around as a branded mascot, a legacy product, while the real power shifts to the Board of Directors. The real players aren’t in the Capitol; they’re in Miami and the Bay Area, managing portfolios, tweaking algorithms that decide who gets paid and who gets banned.

So forget the horse archers and smoking ruins. The future’s got API keys, not battering rams. The U.S. government isn’t falling—it’s forking, and the new repo is under private management.

Silicon Valley isn’t trading spices; they’re trafficking in unlicensed faith, running the same old scam on a species dumb enough to think Andrew Jackson Roman legions is a backup drive. The playbook’s classic—lock down the infrastructure, rebrand extraction as “innovation,” and let the chaos metastasize. The East India Company didn’t lobby governments; it sublet them. A corporate parasite so bloated it finally burst—losing America in the process.

So who pulls the plug on a slow-rolling corporate singularity when democracy is just another app draining battery?

History doesn’t repeat. It open-sources.

Empires don’t fall to barbarians at the gates. They get optimized into oblivion—hollowed out by the guys who promise efficiency but deliver entropy. The East India Company turned tea into tyranny. The new empire runs on cloud storage and Terms of Service nobody reads. Empires don’t fall. They fork.

MUGHALS

The Mughals in the 17th century were a high-functioning, bureaucratic, cosmopolitan empire—rich, centralized, and running on an administrative machine that could churn out roads, forts, and tax revenue with industrial efficiency. But by the time the East India Company got to work, they were a hollowed-out husk, running on inertia, prestige, and nostalgia for past grandeur—like the U.S. government at the dawn of the 21st century, still flexing its state capacity but primed for corporate capture.

The EIC didn’t conquer the Mughals; it subcontracted them. The empire kept its facades—emperors, palaces, courtly rituals—but real power shifted into ledgers, shipping manifests, and contracts enforced at gunpoint. The old administrative machine wasn’t dismantled; it was repurposed, optimized for extraction rather than governance. The 21st-century U.S.? Same deal. The infrastructure stands, but the system’s been rewritten—outsourced, privatized, and slotted into corporate spreadsheets. The real decisions don’t happen in Congress; they happen in boardrooms and server farms. The empire’s still here. It just doesn’t belong to the people who think they run it.

Mughal bankers didn’t just watch their empire collapse—they helped make it happen. These weren’t clueless aristocrats in silk robes; they were hardcore financial operators running one of the most sophisticated credit networks on Earth. They saw the writing on the wall. The Mughal state was bloated, overstretched, hemorrhaging cash on pointless wars. So they hedged their bets.

The East India Company didn’t roll in with just cannon decks and sails stitched with Union Jacks. They came packing something far heavier: predictable protocols. For the Mughals, with their gilded peacock thrones and elephant-mounted artillery, power ran on bug-ridden legacy code—a janky API of imperial favor, capricious local admin permissions, and a taxation script that kept crashing into extortionate shakedowns. Their whole empire was kludged together with blood-marriage alliances and princeware plugins, a medieval OS that froze every time some silk-robed warlord caught a mood.

The Company booted up a beta version of the future. Contracts hard-coded in law, not whispered in courtyards. Revenue streams mapped in clean, legible ledgers. Capital that moved like encrypted packets—no disgruntled warlord rootkits jacking your payload mid-transit. To the Gujarati shipbuilders, Marwari bankers, and Bengali spice syndicates, this wasn’t just governance. It was a governance stack. Why grease palm-drives with silver rupees when you could plug into a standardized API of protection, stamped with the Crown’s TLS encryption?

The Mughal state was a dazzling relic—a 16th-century OS dripping in gemstone GUIs, but prone to fatal system errors every succession cycle. The Company? Version 2.0. A joint-stock corporate kernel, optimized to underwrite risk at scale. Property rights enforced by Redcoat encryption. Supply chains patrolled by sepoy subroutines. Even when the countryside flared into rebel bloatware, the system auto-patched with musket fire and scorched-earth scripts.

Here’s the pivot: The Mughals treated merchants like shareware—useful, but eternally sandboxed beneath aristocratic admin privileges. The Company root-accessed them as stakeholders in a global logistics engine. No more greasing palms. Now you could hedge bets on opium futures, spec plantations, or Bombay bondware—all while the Company’s mercenary middleware kept the ports humming. Yeah, you handed over root access to your autonomy. But in exchange? Firewall-grade stability. A Faustian update, sure, but half the subcontinent’s merchant guilds were already Ctrl+S’ing their futures into Company ledgers.

Once the network effects kicked in, the Mughal system flatlined. Their fractured nodes couldn’t compete with the Company’s ruthless throughput. Delhi’s court? Still pinging requests through an aristocratic OS that crashed if you breathed on it wrong. Meanwhile, the Company’s shareholders were busy compiling a new world order—one where profit margins outranked princes, and the future wasn’t written in Persian couplets, but in quarterly dividend reports.

The takeaway? The Mughals built palaces. The Company deployed infrastructure. And in the end, code beats stone. Welcome to the future—venture capital with a private army, and a share price that only goes up.

They started financing the East India Company. At first, it was just business—loans, letters of credit, maybe some discreet help moving silver around. But soon enough, the EIC wasn’t just a client—it was a replacement operating system. The Company had the one thing the Mughals didn’t: discipline. A vertical command structure, a clear objective (profit), and a ruthless willingness to burn down anything that got in the way. And the bankers? They bet on the better system.

So while the Mughal emperors still sat in their jewel-encrusted palaces, pretending they were in charge, the real power was shifting. The EIC wasn’t some foreign invader kicking down the doors—it was an acquisition. A hostile takeover that the Mughal financiers enabled because their balance sheets told them it was the smart move. The empire didn’t fall. It was liquidated.

FRENCH BRITISH PROXY WARS

The first skirmishes between the British and French East India Companies weren’t wars. They were hostile takeovers with gunpowder. Sure, Paris and London had their flags and treaties, but on the ground, this was a corporate proxy fight playing out inside the crumbling operating system of the Mughal Empire. The Mughals still technically existed, but their governance had been reduced to a buggy, overextended platform that couldn’t push updates fast enough to stop the coming crash.

The Brits and the French weren’t toppling the empire; they were parsing it for vulnerabilities. Mughal governors—who were supposed to be administering provinces—had pivoted to something more like private equity barons, cutting their own deals, issuing their own debt, and outsourcing their security to the highest bidder. The real power wasn’t in Delhi; it was in the bankers’ ledgers, in who got financing and who got starved out. The French ba hi cked one set of warlords, the British backed another, and the whole thing ran on a never-ending cycle of loans, bribes, and battlefield acquisitions.

The British, though—they figured it out first. Robert Clive wasn’t some grand imperial visionary. He was a hostile takeover specialist in a powdered wig. The Battle of Plassey in 1757? That wasn’t a war. It was a leveraged buyout. The British didn’t just defeat the Nawab of Bengal—they bought him out from under himself. Clive bribed his generals, cut a deal with his financiers, and by the time the first shots were fired, the battle was already won on paper.

The Mughals still had their palaces, their rituals, their illusions of sovereignty. But the real empire—the financial, logistical, decision-making infrastructure—had already forked. The East India Company wasn’t a foreign conqueror. It was an update.

THE FALL OF CALCUTTA

The Fall of Calcutta is a textbook East India Company debacle—where incompetence, arrogance, and overreach collide like a botched startup launch, except with cannons and dysentery. The British had been playing fast and loose in Bengal, fortifying their outpost under the guise of “defense,” which Siraj-ud-Daula rightly saw as a hostile takeover attempt. So he did what any irate CEO of a premodern polity would do—he booted them out.

Of course, the British, being masters of failing upward, turned their humiliating loss into a rallying cry. The “Black Hole of Calcutta” narrative, exaggerated or not, became a PR disaster-turned-moral-justification for full-scale intervention. Enter Robert Clive, the corporate fixer with a talent for leveraged buyouts of entire kingdoms. A year later, at Plassey, he steamrolled Siraj-ud-Daula using a mix of bribes, political backstabbing, and superior firepower—essentially pulling off the most lucrative hostile acquisition in history.

From there, the Company went full Silicon Valley: monopolistic control, regulatory capture, and a growth-at-all-costs mentality that led to economic catastrophe (see: the Bengal Famine and general plunder of the subcontinent). Like a venture-backed disaster that keeps getting bailed out, the Company’s spectacular mismanagement was ultimately absorbed by the British government, which restructured it into the Raj—the imperial version of a corporate cleanup.

Mid-18th-century Calcutta wasn’t just a city under siege; it was an early case study in colonial capitalism doing what it does best: breaking things, blaming the locals, then calling it innovation.

1756 LONDON BLACKHOLE

The East India Company isn’t just looting India—it’s wrecking Britain too. Khartoum’s gone, British industry gutted, Indian industries torched. The trade empire? A demolition job in real-time. London bankrolls the chaos, but the machine’s eating its own tail. The Company might be stacking gold in the short term, but it’s siphoning its future out in slow-motion collapse. The raw resources and capital that fueled it? Spent, burned, and bled dry. The real collapse? Still loading.

Picture it—a proto-corporate leviathan, the East India Company, metastasizing across the ganglia of empire. Its tendrils, slick with colonial grease, punched through hemispheres, rewiring the agrarian sinews of England and America into a dystopian feedlot for capital. This wasn’t mere trade; it was a binary plague, a virus of extraction coded in tea, textiles, and human debt.

For the yeoman ghosts of England, the EIC’s algorithms were blunt-force trauma. Their looms? Obsolete wetware next to Bengal’s hyperproductive textile nodes. The Company flooded London’s markets with calicoes cheaper than sin, collapsing local economies into luddite rage. Farmers, once backbone of the shires, found themselves beta-testing poverty—their wool markets gutted, their fields now fallow server farms feeding nothing but the Company’s dividend streams.

Across the Atlantic, the American dirt-grinders fared worse. The EIC’s mercantile OS locked them into a closed-loop system: harvest tobacco, indigo, grain—dump it into the Company’s black-box holds—watch profits evaporate like rum in a Portsmouth tavern. The Navigation Acts? Draconian DRM, ensuring colonial crops cycled back through London’s tollgates, taxes skimmed like bandwidth fees. No open-source markets here, no peer-to-peer trade. Just a raw deal, buffering in perpetuity.

And the kicker? The EIC’s corporate sovereignty rendered them untouchable—a state-sponsored rogue AI, answerable only to shareholders feasting on quarterly reports stained with Bengal famine and Appalachian debt. Farmers? Meatware. Expendable nodes in a network optimized for tea-slicked opulence and shareholder euphoria.

By the 1750s, the feedback loop was clear: the EIC’s greedware had bricked agrarian lifeways, replacing them with a glitched ecosystem of dependency and decay. English cottages crumbled; American silos stood half-empty, their contents siphoned into the Company’s fiber-optic clipper ships, data packets of wealth routing eastward.

This wasn’t commerce. It was early-stage corporatocracy, a preview of the meatgrinder future—where the farmer’s sweat cooled into balance sheets, and the land itself became a backdoored asset, ripe for liquidation.

Welcome to the first draft of the Anthropocene. The East India Company just CTRL-ALT-DELETED your livelihood.

The Three-Headed Beast: The East India Company’s Internal Power Struggle

1. The London Merchants—The Data Brokers of Empire

Picture them: powdered wigs, candlelit chambers, ledgers inked in blood. The EIC directors in Leadenhall Street were an old-world cartel of proto-venture capitalists, watching ticker tapes of bullion, textiles, and narcotics flow through their networks.

To them, India was an economic abstraction, a ledger entry, a fluctuating stock price. They wanted smooth, efficient trade—less war, more profit. Rule from a distance, a soft touch on the tiller. Keep the money moving, keep the Crown happy.

Their nightmare? The second head of the beast—Company men on the ground, playing empire-builders with their investments. The scam worked like this: the London traders needed profits, the military needed payroll, and the Company men in Bengal needed to keep the whole racket spinning without triggering a total implosion. Everyone had a cut, everyone had a reason to look the other way, and as long as the loot flowed back to London, nobody asked too many questions.

The shareholders back in London were insulated from the horrors in Bengal. All they cared about was the dividend checks. How did the Company keep the money flowing even after the famine? Simple: monopolies and war economies. The Company flooded China with opium, jacked up prices on Bengal’s surviving textile industry, and strong-armed local rulers into taking out predatory loans—loans that could only be paid back in land or trade concessions.

2. Bengal’s Tax Farmers—The Bloodsuckers on the Ground

The Company didn’t do the dirty work directly. No, that was for the zamindars, the tax farmers, local enforcers who squeezed the landowners and peasants like a lemon with no juice left. These guys were middlemen, and middlemen always take their cut. If a district owed 100,000 rupees, the zamindar would shake the locals down for 120,000, pocketing the extra 20K. Meanwhile, the actual revenue demand from the Company remained brutally fixed—even when the famine hit, even when the fields were bare.

3. The Company Men—Running Private Grifts While London Slept

Every British official in Bengal—from the big-shot governor to the low-level scribblers—had a side hustle. These weren’t just civil servants; they were traders, merchants, loan sharks, and land speculators with monopoly privileges. A Company factor (think corporate middle manager) would get rich off “presents” from desperate Indian elites trying to hold onto their lands. If you were a rajah or a merchant and you didn’t pay up? Well, your estates might suddenly be seized for “failure to meet revenue targets.”

On the other side of the world, East India Company officials in Bengal weren’t just merchants. They were kings in all but name. Robert Clive didn’t sip tea; he swallowed kingdoms. These men didn’t care about board meetings in London—they were busy forging their own feudal dynasties, making and breaking Indian rulers at gunpoint.

To them, India wasn’t a market—it was theirs. A vast, sweating goldmine of land revenue, taxed to the bone, fueling their personal fortunes. They played politics with native rulers like a sick parlor game, shifting alliances while extracting wealth through the East India Company’s bureaucratic tendrils.

London hated them but couldn’t ignore them. After all, their war chests were financing the entire operation.

4. The Military—Paid in Corrupt Coin

Running a private army the size of the East India Company’s required cash—a lot of it. But official salaries weren’t enough, so officers ran their own freelance extortion rings. British commanders auctioned off officer commissions to the highest bidder, meaning the most ruthless, well-connected (not the most competent) men got command. Meanwhile, sepoy soldiers—Indian recruits—were underpaid and overworked, leading to a powder keg of resentment that would eventually explode in 1857.

FAMINE

ECOLOGICAL DISASTER

Ecologically, the damage was total. Forests were leveled to run opium export scripts. Rivers rerouted to float tea-barge logistics chains. The Company installed a monocropping firmware so destructive even the soil began to fail. By the time the Crown nationalized the whole enterprise in 1858, India wasn’t a colony—it was a bricked device, a captive API feeding Britain’s industrial mainframe. The British government hit CTRL-ALT-DEL, but the rootkits stayed.

The East India Company: Beta-Testing Climate Austerity

Back in the 1770s, the EIC wasn’t just a corporation. It was a climate-crisis profiteer, running a beta version of disaster capitalism. Bengal was their lab. Monsoons failed? Perfect. They’d already installed a taxware exploit to hoover up grain reserves while peasants starved. The Bengal Famine of 1770 wasn’t a tragedy—it was a boardroom calculation. Ten million dead? Just collateral code in their ledger.

The Algorithm:

- Climate Denial 0.1: Ignore drought signals.

- Austerity Firmware: Tax the soil until it cracks.

- Extract & Exit: Sell the corpses’ land to speculators.

The EIC didn’t invent climate chaos. They just monetized its entropy.

The 1770 famine wasn’t a bug—it was the business model. A beta test for necrocapitalism, where hunger wasn’t a byproduct but the proof of concept. Profit engines didn’t run on coal or oil—they ran on bodies. On the slow cremation of a starving province. On harvests funneled into corporate windfalls while the countryside choked in silence.

There was no “misallocation.” That’s the language of polite genocide. The Company auctioned Bengal’s grain to speculators and hoarders while the poor were reduced to famine bread—dirt, leaves, powdered bone. Mothers boiled leather sandals to hush their children’s hunger screams. Fields weren’t just fallow—they were erased. Not a failed crop, but a deleted biosphere.

And those “rogue agents” in Calcutta, sipping claret on shaded verandas? That wasn’t corruption. That was the OS functioning as designed. They were the wetware interface of a system that calculated human life in rupees-per-ton, where depreciation began at birth and ended in a shallow grave.

Now zoom out.

A boardroom in London: mahogany tables sticky with rum and blood-merchant spreadsheets. Gentleman capitalists discussing death yields in sanitized euphemism. The Crown’s mouthpieces spinning laissez-faire fairy tales—free markets, invisible hands—while Company tax farmers throttled Bengal like a tourniquet around the throat of a civilization.

You want innovation? Try venture colonialism, v1.0. Starvation scaled like a growth hack. Shareholder value measured in corpses per quarter.

Fast forward.

Swap grain silos for server farms. Zamindars for gig-economy algos. The same extraction logic, now encrypted. Neoliberalism as a legacy patch over colonial firmware. The branding changed. The boot stayed the same.

Somewhere on the dark web, a British history podcast reenacts Clive’s plunder like cosplay. TikTok historians in ring lights and waistcoats giggle through genocide trivia. The nostalgia’s monetized. The blood, photoshopped sepia.

By the 1770s, the machine was overheating. The Bengal Famine cracked its engine block.

- The revenue model—agrarian taxes wrung from starving peasants—flatlined as a third of Bengal’s population died or fled.

- The trade network—an opium-laced circuitry of silk, spices, and silver—shorted out. The famine didn’t just kill farmers; it kneecapped weavers, traders, the entire export chain.

- Corruption metastasized. Company officials skimmed off the top while the core system rotted.

London took notice—not out of compassion, but because the whole operation was spiraling.

The 1772 bailout triggered the Regulating Act of 1773—the beginning of the end. The famine wasn’t the kill shot, but it exposed the terminal illness. The East India Company shifted from empire-builder to parasite in decline.

What followed was a slow-motion collapse—devoured by the same system that birthed it. Corporate greed burns too bright, collapses under its own weight, then gets absorbed by the state once the damage is unignorable.

BAILOUT

By 1772, the East India Company was cracking under the weight of its own corruption. It had conquered a subcontinent, but now it was too bloated to sustain itself. When the crash came, the Company begged Parliament for a bailout. And Parliament? Too many MPs were shareholders. Instead of breaking it up, they nationalized its failures and privatized its profits—the first move toward direct British rule.

Corruption wasn’t a flaw. It was the system. It kept tax farmers brutal, Company men fat, the military obedient, and London shareholders drunk on dividends. But like all machines built on greed, it couldn’t last. The famine decimated the labor force. The tax base shrank. When the money dried up, the system began to cannibalize itself. By the time the British government stepped in, the Company was already a zombie—dead on its feet, waiting to be put down in 1858.

This wasn’t conquest. It wasn’t governance. It was a long, bloody, bureaucratic heist—and in the end, even the heisters lost control.

Ask a neoliberal shill—sleek in their exosuit of market dogma, jacked into capital’s eternal now—and they’ll hiss through a smirk:

“Colonialism, mate. A bug in the code. Deregulate, decolonize, let the invisible hand CTRL-Z the whole mess.”

Their optics flicker with ghost-pixel Adam Smith, cherry-picked and blurred, as if the East India Company were just a bad IPO. A startup that scaled too fast. Too greedy. Too inefficient in its extraction metrics.

Corner a Brit—some Union Jack-tatted relic nursing warm lager in a Weatherspoon’s simulacrum—and they’ll bark:

“Rogue agents! Privateers gone feral! Nothing to do with Crown and Country, innit?”

Their denial hangs thick, a smog of performative amnesia etched into national firmware. The Company? Just a glitch in an otherwise noble project. A few greedy suits exploiting loopholes.

Both sides are peddling mythware. The East India Company wasn’t a bug—it was the operating system. A proto-corporatocracy. A fractal of violence where profit algorithms met musket diplomacy. Those “rogue agents”? Not outliers. They were alpha testers of shareholder colonialism, beta-launched before Whitehall even pretended to govern.

Imagine a boardroom where stock prices dictate troop deployments, where quarterly reports justify massacres. A corporate singularity, eating nations from the inside out. And the Brits? Venture capitalists in powdered wigs, quietly monetizing chaos while polishing the Crown’s PR.

Now? Swap clipper ships for fiber-optics, tea for data. The Company’s DNA metastasized into every transnational squatting in offshore server farms, rewriting legality in its image. Neoliberals still chant the gospel of “disruption.” Brits still rewrite history.exe to skip the crash logs.

System Overload: The Inevitable Collapse

The Company didn’t implode because of outside enemies—it crashed because its factions were feeding on each other. Merchants demanded cash flow. The Bengal faction craved control. The military pushed for endless war. Nobody wanted oversight. The British government watched in horror as their pet corporation mutated into a rogue state.

- 1770s: The Regulating Act tries to leash the beast.

- 1780s: Pitt’s India Act adds red tape and London control.

- 1830s: Monopoly revoked; “free trade” enforced.

- 1850s: The overconfident military crushes a mutiny with industrial-scale brutality.

- 1858: System crash. The Company is nationalized, gutted, and rebranded as the British Raj.

- 1874: Dead.

But its ghost lingered. It left economies warped around its trade routes, legal systems stitched from its codes, wars fought in its image. The Company collapsed, but its code still runs in the background.