Deep space is a technique used in filmmaking to create a sense of depth and distance in a scene, typically by manipulating perspective and creating the illusion of three-dimensional space on a two-dimensional screen. There are a number of different elements that contribute to the creation of deep space, including perspective, size difference, movement, camera movement, and various optical effects. Here are some of the key elements of deep space and examples of how they have been used in films:

Perspective:

The convention of perspective . . . centers everything in the eye of the beholder. It is like a beam from a lighthouse—only instead of traveling outward, appearances travel in. The conventions called those appearances reality. The use of perspective is one of the most fundamental techniques in creating deep space in film. Perspective refers to the way objects appear to change in size and distance depending on their position relative to the viewer. By using one-, two-, or three-point perspective, filmmakers can create the illusion of depth and distance in a scene. Perspective makes the single eye the center of the visible world. Everything converges on the eye as to the vanishing point of infinity. The visible world is arranged for the spectator as the universe was once thought to be arranged for God.

One-point perspective:

In one-point perspective, all lines in the scene converge on a single vanishing point, typically positioned in the center of the frame. This creates a strong sense of depth and distance in the scene. An example of one-point perspective can be seen in the scene in “The Shining” where Jack Torrance is shown walking down the long hallway of the Overlook Hotel. In “The Grand Budapest Hotel,” there is a shot of the hotel’s lobby that uses one point perspective to create a sense of depth and grandeur. The shot is perfectly symmetrical, with the walls converging at a single point in the distance. In “The Godfather,” there is a shot of Michael sitting at a restaurant table with his bodyguards behind him. The shot uses one point perspective to create a sense of tension and unease, as the bodyguards seem to be looming over Michael and the walls of the restaurant seem to be closing in on him

In “The Grand Budapest Hotel,” there is a shot of the hotel’s lobby that uses one point perspective to create a sense of depth and grandeur. The shot is perfectly symmetrical, with the walls converging at a single point in the distance.

In “The Godfather,” there is a shot of Michael sitting at a restaurant table with his bodyguards behind him. The shot uses one point perspective to create a sense of tension and unease, as the bodyguards seem to be looming over Michael and the walls of the restaurant seem to be closing in on him.

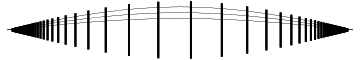

Two-point perspective:

In two-point perspective, lines in the scene converge on two vanishing points, typically positioned on opposite sides of the frame. This creates a sense of depth and distance, as well as a feeling of balance and symmetry. An example of two-point perspective can be seen in the scene in “Blade Runner” where Deckard is shown walking through the futuristic cityscape. In “The Shawshank Redemption,” there is a scene where Andy is working in the prison library. The shot uses two point perspective to create a sense of depth and distance, as the shelves of books seem to stretch off into the distance on either side of him. In “The Social Network,” there is a shot of Mark Zuckerberg walking through the Harvard campus. The shot uses two point perspective to create a sense of space and scale, as the buildings on either side of him seem to tower over him. The different parts blend together seamlessly via the telegraph effect (as in a series of telegraph poles extending far to the left and right of the viewer, while staying parallel to the picture plane)

Three-point perspective:

Three point perspective is similar to two point perspective, but also includes a third vanishing point that is either above or below the horizon line. This creates a more dynamic and dramatic effect, as objects in the scene appear to be tilted and distorted, as if the viewer is looking up or down at them. Three point perspective is often used in extreme or unusual camera angles, such as high-angle shots or low-angle shots. It can also be used to create a sense of disorientation or unease in the viewer, as the image appears to be warped or off-kilter. In three-point perspective, lines in the scene converge on three vanishing points, typically positioned at the top, bottom, and sides of the frame. This creates a sense of extreme depth and distance, as well as a feeling of disorientation and chaos. An example of three-point perspective can be seen in the scene in “Inception” where the characters are shown navigating the complex dream world. In “The Matrix,” there is a famous shot where Neo is dodging bullets in slow motion. The shot uses three point perspective to create a sense of disorientation and chaos, as the bullets seem to be flying in from all directions. In “The Revenant,” there is a scene where Hugh Glass is crawling through the forest after being attacked by a bear. The shot uses three point perspective to create a sense of disorientation and confusion, as the camera seems to be rotating around Glass and the forest seems to be closing in on him.

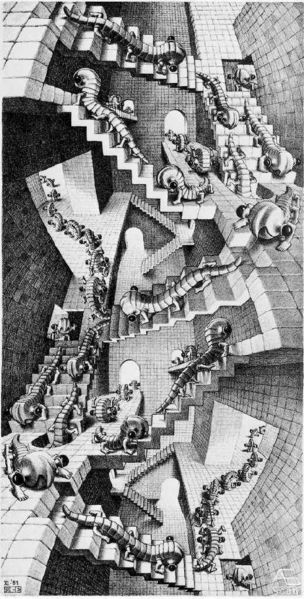

A vanishing point is simply a point in the picture where parallel lines converge, and so there is no mathematical distinction between a zenith, nadir, and point on the horizon. In House of Stairs single vanishing points are used as zenith, nadir, and horizon.

Size difference:

Another key element of deep space is the use of size difference to create a sense of depth and distance. By showing objects of different sizes in the foreground and background of a scene, filmmakers can create the illusion of a vast space stretching out into the distance. An example of size difference can be seen in the opening shot of “Lawrence of Arabia,” where a small figure is shown riding a camel across a vast desert landscape. In the classic movie “2001: A Space Odyssey,” director Stanley Kubrick used size difference to great effect in the scenes where the character Dave Bowman is shown walking through the enormous, cavernous interior of the spacecraft. By showing Bowman as a tiny figure in a vast, almost infinite space, Kubrick was able to create a sense of awe and wonder that helped to convey the enormity of the unknown depths of space. The scene in the movie “Jurassic Park” where the T-Rex is first introduced is another great example of size difference. The massive size of the dinosaur compared to the human characters emphasizes the danger and threat posed by the creature, and helps to create a sense of terror and excitement in the viewer. In the movie “Avatar,” director James Cameron uses size difference to great effect in the scenes where the characters explore the vast, alien landscape of the planet Pandora. By showing the tiny figures of the human explorers against the towering trees and mountains of the planet, Cameron is able to create a sense of wonder and awe in the viewer, and convey the vastness and scale of the alien world.

Movement:

Movement is also a key element of deep space, as it can create the illusion of distance and depth in a scene. By showing objects moving towards or away from the camera, filmmakers can create a sense of depth and distance. An example of movement can be seen in the famous dolly zoom shot in “Jaws,” where the camera moves backwards while simultaneously zooming in, creating a sense of disorientation and unease. Camera movement: In addition to object movement, the movement of the camera itself can also create a sense of deep space. By using techniques like tracking shots and crane shots, filmmakers can create the illusion of the camera moving through three-dimensional space. An example of camera movement can be seen in the famous opening shot of “Touch of Evil,” where the camera follows a car through the streets of a Mexican border town. In the movie “The Revenant,” director Alejandro González Iñárritu uses movement to create a sense of scale and distance in the sweeping landscapes of the American frontier. The camera often moves in long, slow shots that follow the characters as they travel through the wilderness, emphasizing the vastness and beauty of the natural world. In the movie “The Shining,” director Stanley Kubrick uses camera movement to create a sense of unease and disorientation in the scenes where the character Jack Torrance explores the haunted hotel. The camera often moves in slow, deliberate shots that follow Torrance through the twisting, labyrinthine corridors of the hotel, creating a sense of depth and distance that heightens the tension and suspense of the scene.

Textural diffusion:

Textural diffusion involves the use of textures and patterns to create a sense of depth and distance in a scene. This can be achieved by using fabrics, surfaces, or other materials that have a distinct texture or pattern, such as wood grain or brickwork. By using these materials in the foreground and background of a scene, filmmakers can create a sense of depth and distance. An example of textural diffusion can be seen in the opening shot of “Blade Runner,” where the camera moves over the textured surfaces of a futuristic cityscape.

- In the movie “Blade Runner,” director Ridley Scott uses textural diffusion to create a sense of depth and complexity in the futuristic cityscapes of Los Angeles. The city is depicted as a dense, labyrinthine metropolis, with towering skyscrapers and sprawling neon-lit streets, all of which are covered in a dense layer of grime and decay that gives the city a sense of age and history.

- In the movie “Mad Max: Fury Road,” director George Miller uses textural diffusion to create a sense of depth and dimensionality in the post-apocalyptic wasteland where the story takes place. The landscape is depicted as a harsh, unforgiving environment, with rocky outcroppings, sand dunes, and other natural features that are covered in a thick layer of dust and sand, which gives the world a sense of age and weariness.

- In the movie “The Grand Budapest Hotel,” director Wes Anderson uses textural diffusion to create a sense of depth and richness in the luxurious interiors of the hotel. The walls, floors, and furnishings are all covered in intricate patterns and textures, from the ornate floral wallpaper to the plush velvet drapes, which gives the hotel a sense of opulence and grandeur.

- In the movie “The Dark Knight,” director Christopher Nolan uses textural diffusion to create a sense of depth and dimensionality in the scenes where the characters explore the dark, gritty streets of Gotham City. The walls of the buildings are covered in rough, weathered bricks, and the streets are filled with cracked pavement and trash, which gives the city a sense of history and decay.

- In the movie “The Shape of Water,” director Guillermo del Toro uses textural diffusion to create a sense of depth and richness in the underwater world where the story takes place. The walls and floors of the underwater laboratory are covered in intricate patterns and textures, from the smooth curves of the tiles to the delicate patterns on the wallpaper, which gives the world a sense of beauty and wonder.

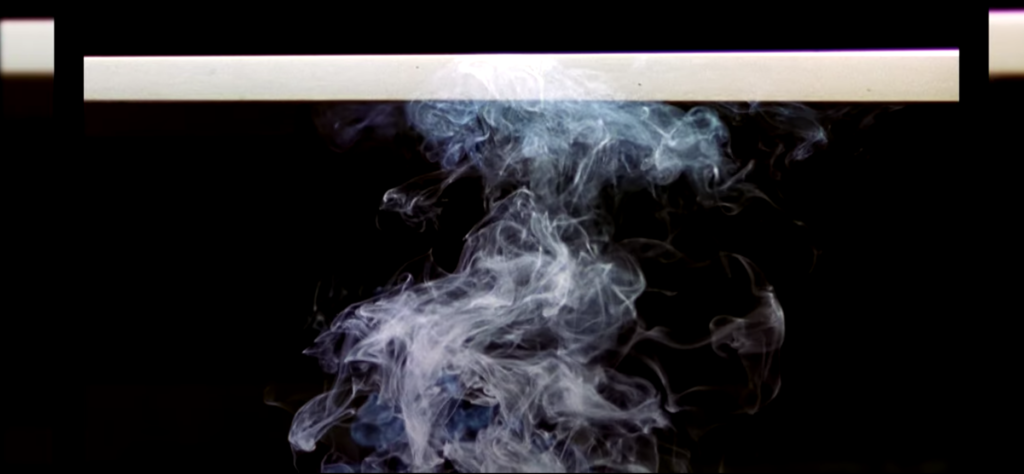

Aerial diffusion:

Aerial diffusion involves the use of atmospheric haze to create a sense of distance and depth in a scene. This can be achieved by using smoke, mist, or other substances that create a subtle layer of haze in the air. By using this haze in the background of a scene, filmmakers can create a sense of depth and distance. An example of aerial diffusion can be seen in the opening shot of “Apocalypse Now,” where the camera moves through a layer of smoke and haze to reveal a vast jungle landscape.

- In the movie “The Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring,” director Peter Jackson uses aerial diffusion to create a sense of distance and scale in the sweeping landscapes of Middle Earth. The rolling hills and misty valleys are often shrouded in a layer of atmospheric haze, which gives the scenes a sense of depth and distance.

- In the movie “Blade Runner 2049,” director Denis Villeneuve uses aerial diffusion to create a sense of depth and dimensionality in the futuristic cityscapes of Los Angeles. The skyline is often obscured by a layer of smog and haze, which gives the city a sense of scale and complexity.

- In the movie “Apocalypse Now,” director Francis Ford Coppola uses aerial diffusion to create a sense of distance and foreboding in the scenes where the characters navigate the dense jungle of Vietnam. The thick foliage is often shrouded in a layer of mist and haze, which gives the jungle a sense of mystery and danger.

- In the movie “The Revenant,” director Alejandro González Iñárritu uses aerial diffusion to create a sense of scale and majesty in the sweeping landscapes of the American frontier. The rolling hills and vast open spaces are often shrouded in a layer of fog and mist, which gives the scenes a sense of depth and distance.

- In the movie “Avatar,” director James Cameron uses aerial diffusion to create a sense of depth and wonder in the lush, alien world of Pandora. The dense foliage and towering trees are often shrouded in a layer of mist and atmospheric haze, which gives the world a sense of beauty and otherworldliness.

Shape change:

Shape change involves the use of changes in the shape of objects to create a sense of depth and distance in a scene. This can be achieved by using objects that have a distinct shape or silhouette, such as buildings or trees, and positioning them in the foreground and background of a scene. By using these objects to create a sense of depth and distance, filmmakers can create a more immersive and visually engaging scene. An example of shape change can be seen in the opening shot of “The Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring,” where the camera moves over the distinct shapes of mountains and hills to create a sense of depth and distance.

- In the movie “Inception,” director Christopher Nolan uses shape change to create a sense of disorientation and distortion in the dream world. As the characters move through the different levels of the dream, the shape and orientation of the buildings and landscapes constantly shift and change, creating a surreal and immersive experience for the viewer.

- In the movie “Blade Runner,” director Ridley Scott uses shape change to create a sense of scale and complexity in the futuristic cityscape of Los Angeles. The towering skyscrapers and sprawling buildings are often shown from a distance, with their unique shapes and silhouettes standing out against the city skyline.

- In the movie “Star Wars,” director George Lucas uses shape change to create a sense of depth and dimensionality in the iconic space battles. The distinctive shapes of the spaceships and starfighters are used to create a sense of scale and distance, as the ships move in and out of the foreground and background of the scenes.

- In the movie “The Matrix,” directors Lana and Lilly Wachowski use shape change to create a sense of distortion and disorientation in the digital world of the Matrix. The walls and surfaces of the buildings and landscapes constantly shift and change, creating a surreal and unsettling environment for the characters.

- In the movie “The Grand Budapest Hotel,” director Wes Anderson uses shape change to create a sense of whimsy and playfulness in the ornate and elaborate set design. The unique shapes and patterns of the buildings and landscapes are used to create a sense of depth and dimensionality, as the characters move through the intricate and surreal world of the hotel.

Tonal change:

Tonal change involves the use of changes in lighting and color to create a sense of depth and distance in a scene. This can be achieved by using different shades of light and dark, as well as different colors, in the foreground and background of a scene. By using these tonal changes to create a sense of depth and distance, filmmakers can create a more immersive and visually engaging scene. An example of tonal change can be seen in the opening shot of “The Godfather,” where the camera moves from a darkened room to a brightly lit street, creating a sense of depth and distance.

- In the movie “The Godfather,” director Francis Ford Coppola uses tonal change to create a sense of depth and distance in the scenes set in Don Corleone’s office. The dark wood paneling and furniture in the foreground are contrasted with the lighter walls and ceiling in the background, creating a sense of depth and dimensionality.

- In the movie “The Revenant,” director Alejandro González Iñárritu uses tonal change to create a sense of distance and isolation in the wilderness. The cold, blue tones of the snow and sky in the background contrast with the warmer, earthy tones of the foreground, creating a sense of depth and distance.

- In the movie “La La Land,” director Damien Chazelle uses tonal change to create a sense of depth and dimensionality in the musical numbers. The brightly colored costumes and sets in the foreground are contrasted with the darker, more muted backgrounds, creating a sense of depth and distance.

- In the movie “The Matrix,” directors Lana and Lilly Wachowski use tonal change to create a sense of depth and dimensionality in the digital world of the Matrix. The greenish-blue tones of the Matrix contrast with the warmer, more natural tones of the “real world,” creating a sense of depth and distance between the two.

- In the movie “The Grand Budapest Hotel,” director Wes Anderson uses tonal change to create a sense of whimsy and playfulness in the elaborate set design. The bright, vibrant colors of the foreground are contrasted with the more muted, pastel tones of the background, creating a sense of depth and dimensionality in the intricate and surreal world of the hotel.

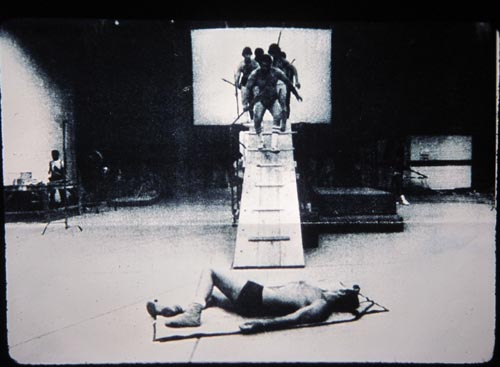

Up-down position:

Up-down position involves the use of positioning objects at different heights to create a sense of depth and distance in a scene. This can be achieved by positioning objects in the foreground and background of a scene at different heights, such as having a character in the foreground and a building in the background. By using these different positions to create a sense of depth and distance, filmmakers can create a more immersive and visually engaging scene. An example of up-down position can be seen in the opening shot of “Gone with the Wind,” where the camera moves over the heads of soldiers lying on the ground to reveal a vast landscape stretching out into the distance.

- In the movie “Inception,” director Christopher Nolan uses up-down position to create a sense of disorienting depth in the dream sequences. Characters are shown walking and fighting on walls and ceilings, and the camera often rotates to create a sense of disorientation and confusion.

- In the movie “Jurassic Park,” director Steven Spielberg uses up-down position to create a sense of scale and perspective in the scenes with the dinosaurs. Characters are shown in the foreground, with towering dinosaurs in the background, creating a sense of depth and awe.

- In the movie “Avatar,” director James Cameron uses up-down position to create a sense of depth and scale in the alien world of Pandora. Characters are shown in the foreground, with massive floating mountains and alien wildlife in the background, creating a sense of depth and wonder.

- In the movie “The Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring,” director Peter Jackson uses up-down position to create a sense of scale and perspective in the scenes with the giant Balrog. Characters are shown in the foreground, with the massive Balrog towering over them in the background, creating a sense of depth and danger.

- In the movie “Up,” directors Pete Docter and Bob Peterson use up-down position to create a sense of whimsy and playfulness in the scenes with the floating house. The house is shown in the foreground, with the sprawling city and landscape in the background, creating a sense of depth and wonder.

Overlap:

Overlap involves the use of overlapping objects to create a sense of depth and distance in a scene. This can be achieved by positioning objects in the foreground and background of a scene so that they partially obscure each other. By using this overlap to create a sense of depth and distance, filmmakers can create a more immersive and visually engaging scene. An example of overlap can be seen in the opening shot of “Chinatown,” where the camera moves over a crowded city street, with various objects overlapping each other to create a sense of depth and distance.

- In the movie “Blade Runner,” director Ridley Scott uses overlap to create a sense of depth in the futuristic cityscapes. Buildings and other structures are shown in the foreground, with other structures and flying cars partially obscured in the background, creating a sense of scale and complexity in the city.

- In the movie “The Dark Knight,” director Christopher Nolan uses overlap to create a sense of chaos and confusion in the action scenes. Characters and objects are shown in the foreground, with other characters and objects partially obscured in the background, creating a sense of disorientation and danger.

- In the movie “Mad Max: Fury Road,” director George Miller uses overlap to create a sense of urgency and danger in the high-speed chase scenes. Cars and other vehicles are shown in the foreground, with other vehicles and obstacles partially obscured in the background, creating a sense of speed and danger.

- In the movie “The Matrix,” directors Lana and Lilly Wachowski use overlap to create a sense of depth and complexity in the scenes set inside the Matrix. Characters and objects are shown in the foreground, with other characters and objects partially obscured in the background, creating a sense of the vastness and complexity of the digital world.

- In the movie “Interstellar,” director Christopher Nolan uses overlap to create a sense of distance and scale in the scenes set in deep space. Stars and planets are shown in the foreground, with other celestial objects partially obscured in the background, creating a sense of the vastness and complexity of the universe.

- In the movie “Lost in Translation,” director Sofia Coppola uses overlap to create a sense of loneliness and isolation in the Tokyo cityscapes. Characters are shown in the foreground, with other characters and buildings partially obscured in the background, creating a sense of distance and detachment.

- In the movie “Moonlight,” director Barry Jenkins uses overlap to create a sense of intimacy and connection between characters. Characters are shown in the foreground, with other characters partially obscured in the background, creating a sense of emotional depth and complexity.

- In the movie “Lady Bird,” director Greta Gerwig uses overlap to create a sense of time and place in the coming-of-age story set in Sacramento. Characters and objects are shown in the foreground, with other characters and objects partially obscured in the background, creating a sense of the passing of time and the changing of seasons.

- In the movie “The Grand Budapest Hotel,” director Wes Anderson uses overlap to create a sense of depth and complexity in the elaborate sets and miniatures. Characters and objects are shown in the foreground, with other characters and objects partially obscured in the background, creating a sense of the intricate and whimsical world of the hotel.

- In the movie “Her,” director Spike Jonze uses overlap to create a sense of distance and separation between the human characters and the artificial intelligence character. Characters are shown in the foreground, with the AI character partially obscured in the background, creating a sense of the technological gap between them.

Focus:

Focus involves the use of selective focus to create a sense of depth and distance in a scene. This can be achieved by selectively focusing. Focus is a key element of deep space that involves the use of selective focus to create a sense of depth and distance in a scene. By selectively focusing on certain objects in the foreground or background, filmmakers can create a sense of depth and distance that draws the viewer into the scene. One example of the use of focus in deep space can be seen in the opening shot of “Saving Private Ryan.” In this scene, the camera moves over a beach where soldiers are landing during the D-Day invasion. As the camera moves forward, it focuses on various objects in the foreground and background, such as a soldier’s hand gripping a landing craft, a piece of shrapnel on the ground, and the smoke and chaos in the background. By selectively focusing on these objects, the filmmakers create a sense of depth and distance that draws the viewer into the scene and conveys the intensity and chaos of the moment. Another example of the use of focus in deep space can be seen in the film “The Departed.” In one scene, the camera moves through a crowded bar, focusing on different characters as they interact with each other. By selectively focusing on different characters in the foreground and background, the filmmakers create a sense of depth and distance that draws the viewer into the scene and gives a sense of the complex web of relationships and interactions between the characters. In both of these examples, the use of selective focus is a key element of deep space that creates a sense of depth and distance in the scene. By using focus in this way, filmmakers can create a more immersive and visually engaging experience for the viewer.