Beginnings: Inviting entry point into story. A good hook gets to interesting and relevant details of character, setting or plot quickly as wells as asking interesting questions

Beginnings: Inviting entry point into story. A good hook gets to interesting and relevant details of character, setting or plot quickly as wells as asking interesting questions

For the reader, it’s rather like wearing earphones plugged into someone’s brain, and monitoring an endless tape-recording of impressions, reflections, questions, memories and fantasies, triggered by physical sensations and the association of ideas. Unlike stream-of-consciousness, which is not punctuated an interior monologue can be integrated into a third-person narrative. It’s a character talking/thinking, using words specific to that character, making assumptions, mistaken judgements, conclusions RIGHT FOR THAT CHARACTER.

Interior monologues in literature are a narrative technique that provides insight into a character’s thoughts, feelings, and inner experiences. They allow readers to delve into a character’s consciousness, providing a deeper understanding of their motivations and emotions. Here’s a list of types of interior monologues commonly found in literature:

These various types of interior monologues serve to enrich characters, deepen the narrative, and provide readers with a more profound understanding of the human psyche. They are a powerful tool for authors to explore their characters’ inner worlds and connect readers on a deeper emotional level.

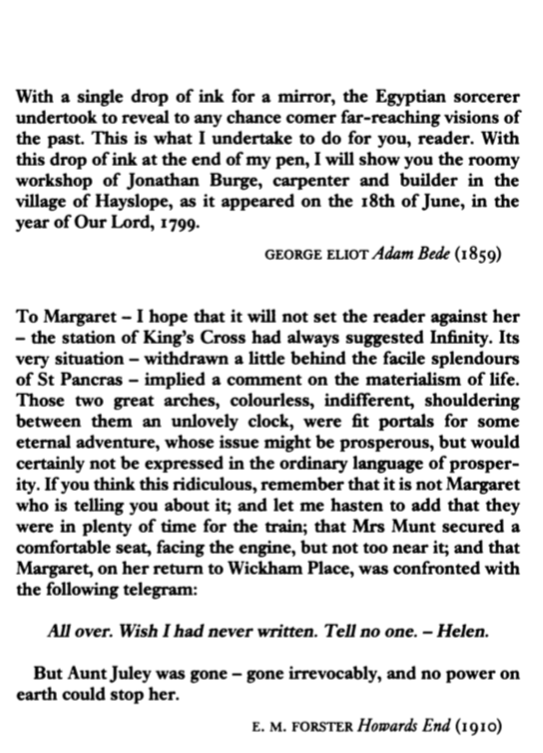

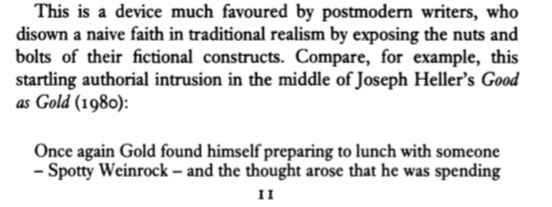

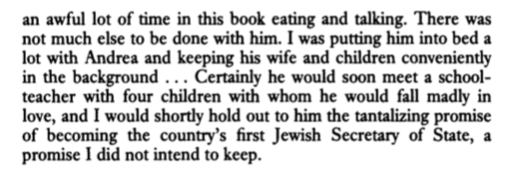

Intrusive Author: Eliot, Tolstoy and earlier An omniscient narrator who, in addition to reporting the events, allows the novel to be used for general moral commentary on human life, sometimes in the form of brief digressive essays interrupting the narrative.

Modern fiction has tended to suppress or eliminate the authorial voice, by presenting the action through the characters consciousness, or by handing over to them the narrative task itself. When the intrusive voice is employed, it’s usually with a ironic undertones.

In the vast landscape of literature, there exists a unique narrative technique known as the “Intrusive Author.” This approach involves an omniscient narrator who not only reports the events of the story but also steps beyond the boundaries of the narrative to provide general moral commentary on human life. Often presented in the form of digressive essays interrupting the main storyline, this technique allows authors to delve into profound reflections and philosophical musings. Two illustrious authors who masterfully wielded the Intrusive Author technique are George Eliot and Leo Tolstoy. Their works, alongside earlier examples, showcase the power of this narrative device to enrich storytelling with profound insights into the human condition.

George Eliot, the pen name of Mary Ann Evans, was a master of the Intrusive Author technique. In her magnum opus, “Middlemarch,” Eliot weaves a tapestry of interconnected lives in the fictional English town of Middlemarch. Throughout the novel, the omniscient narrator frequently steps forward to impart wisdom on the complexities of human nature and societal norms. In one such instance, the narrator reflects on the ambitions of the protagonist, Dorothea Brooke, and the consequences of pursuing lofty ideals:

“If we had a keen vision and feeling of all ordinary human life, it would be like hearing the grass grow and the squirrel’s heart beat, and we should die of that roar which lies on the other side of silence.”

This digression not only offers insight into Dorothea’s character but also serves as a universal reflection on the limitations of human perception and the overwhelming intricacies of existence. Eliot’s skillful use of the Intrusive Author technique allows her narrative to transcend the mere chronicle of events, transforming “Middlemarch” into a profound exploration of human aspirations and their inherent limitations.

Leo Tolstoy, in his epic masterpiece “War and Peace,” employs the Intrusive Author technique to great effect. Amidst the tumultuous backdrop of war and social upheaval, Tolstoy interjects philosophical discourses that contemplate the forces shaping history and the nature of free will. In a reflective digression, he ponders the unpredictable course of events and the influence of individuals on historical outcomes:

“The most difficult thing—and for an educated man the most natural—is to do nothing. Here you have wisdom and goodness.”

Tolstoy’s intrusion provides readers with a deeper understanding of the characters’ actions and choices, intertwining the personal with the grand sweep of history. By offering profound moral commentary, he elevates “War and Peace” from a mere historical saga to a profound meditation on the human capacity for agency in the face of destiny.

The Intrusive Author technique, though most prominently displayed by Eliot and Tolstoy, finds roots in earlier works of literature. In Samuel Richardson’s “Pamela,” published in the 18th century, the author employs letters and interspersed moral reflections to comment on virtue, social class, and the struggles faced by the protagonist, Pamela Andrews. Similarly, in Laurence Sterne’s “Tristram Shandy,” the narrator frequently engages in digressive asides, playfully exploring the intricacies of language and the nature of storytelling.

In conclusion, the Intrusive Author technique, exemplified by the works of George Eliot, Leo Tolstoy, and their literary predecessors, offers a profound mode of storytelling. By interjecting digressive essays into the narrative, these authors transcend the boundaries of the plot and use their omniscient voices to impart moral commentary on the human condition. Through this technique, they enrich their narratives with timeless reflections on life, society, and the intricate web of human existence. As readers, we find ourselves not only immersed in captivating stories but also confronted with profound insights that transcend time and space. The Intrusive Author, with their piercing gaze and wise musings, leaves an indelible mark on literature and our understanding of humanity.

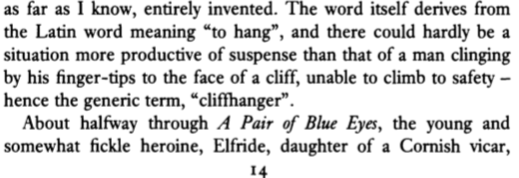

Suspense is a powerful storytelling tool that captivates audiences by creating tension and anticipation. It operates on the principle of withholding information or delaying the resolution of important questions, thereby piquing the audience’s curiosity and keeping them engaged until the climax. There are two main types of questions that suspense raises in the minds of the audience: those related to causality (the “whodunnit?” question) and those concerning temporality (the “what will happen next?” question). These questions are prominently featured in two distinct genres—the detective story and the adventure story.

The detective plays a crucial role in maintaining suspense. Their pursuit of the truth involves strategic thinking, deduction, and the unveiling of hidden connections between seemingly unrelated events. The audience follows the detective’s thought process and becomes emotionally invested in solving the mystery alongside them. This engagement heightens the sense of suspense as they navigate through twists and turns, suspecting various characters and scenarios until the truth is finally unveiled.

With each cliffhanger, the audience experiences sympathetic fear and anxiety, genuinely concerned about the outcome of the protagonist’s predicament. Will they survive? Can they overcome the odds? These questions keep the audience engaged and emotionally invested in the story. As the adventure unfolds, the protagonist must display courage, resourcefulness, and resilience to escape perilous situations, leading to moments of relief and triumph.

Here’s a 10-point list of suspenseful characteristics commonly found in thrillers:

Incorporating these suspenseful characteristics into a thriller ensures that readers or viewers are hooked, eagerly turning pages or glued to their seats, as they journey through the twists and turns of a gripping and thrilling narrative.

Skaz is a fascinating narrative technique that unites a vernacular colloquial style with a naive and immature narrator. The storytelling imitates actual speech, making it almost unintelligible, akin to transcripts of recorded conversations. However, this illusion is precisely what gives the narrative its powerful effect of authenticity and sincerity.

The essence of skaz lies in its ability to capture the unfiltered and raw expression of the narrator. The language used is not polished or refined; instead, it reflects the character’s personality, background, and emotions. This unpretentious approach brings a unique charm to the storytelling, as if the narrator is speaking directly to the reader in a candid, unfiltered manner.

The narrator in a skaz narrative often possesses a childlike or inexperienced perspective, which adds an element of innocence and naivety to the storytelling. This innocent tone allows the audience to see the world through the eyes of the narrator, experiencing events and emotions as they do. This emotional connection fosters empathy and makes the narrative more relatable and engaging.

However, it is essential to note that the use of a naive and colloquial narrator can present challenges for readers. The authenticity of skaz can sometimes make it difficult to decipher the exact meaning of the words and phrases used. Sentences might be fragmented, syntax might be unconventional, and grammar might be relaxed. These intentional deviations from standard language conventions can create an almost poetic rhythm, but they can also demand a bit more effort from the reader to understand the intended message.

Despite these potential challenges, the unconventional style of skaz lends a sense of realism to the narrative. It mirrors the way people actually speak, with all their quirks and colloquialisms. The overall effect is a story that feels organic and genuine, drawing the reader into the world of the narrator and making them feel like a participant in the unfolding events.

In conclusion, skaz is a powerful storytelling technique that combines vernacular colloquial language with a naive and immature narrator. While the resulting narrative may seem almost unintelligible at times, it creates an illusion of authenticity and sincerity that captivates the audience. By immersing readers in the unfiltered thoughts and emotions of the narrator, skaz forges a unique connection between the audience and the story, making it an enriching and memorable literary experience.

Skaz is a narrative style that has been used in literature, and one of the most notable examples is Fyodor Dostoevsky’s “Crime and Punishment.” In this novel, Dostoevsky employs skaz in the character of Marmeladov, a drunk and impoverished man. Marmeladov’s speech is characterized by a fragmented and colloquial style, reflecting his chaotic and emotional state.

Here’s an example of Marmeladov’s skaz speech from “Crime and Punishment”:

“Oh dear, oh dear!…How unfortunate…! Eh, dear friend, there’s a calamity. Listen, dear sir, just a moment, dear fellow! Listen…Dear friend, you see…Katerina Ivanovna…Katerina Ivanovna…murdered…she was kicked…dear friend…a beast…she came to the drunkard…drunk…beast…and she was kicked…in the street…in front of everyone.”

As you can see, Marmeladov’s speech is filled with repetitions, ellipses, and exclamations, reflecting his intoxicated and distressed state of mind.

Another famous example of skaz in literature is Mark Twain’s “The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn.” The character of Huck Finn, a young and uneducated boy, narrates the story in a vernacular colloquial style. Huck’s use of regional dialect and colloquial language gives the narrative an authentic and immersive quality.

Here’s an excerpt from “The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn” showcasing Huck’s skaz-like narrative:

“Well, I got a good going-over in the morning from old Miss Watson on account of my clothes; but the widow she didn’t scold, but only cleaned off the grease and clay, and looked so sorry that I thought I would behave awhile if I could. Then Miss Watson she took me in the closet and prayed, but nothing come of it. She told me to pray every day, and whatever I asked for I would get it. But it warn’t so. I tried it. Once I got a fish-line, but no hooks. It warn’t any good to me without hooks. I tried for the hooks three or four times, but somehow I couldn’t make it work.”

In this passage, Huck’s narration is characterized by simple language, grammatical errors, and colloquial expressions, creating a distinctive voice for the character.

Both “Crime and Punishment” and “The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn” demonstrate how the skaz narrative technique can add depth and authenticity to characters and immerse readers in the world of the story.

Huge in the 1800’s. Samuel Richardson’s long, moralistic and psychologically acute epistolary novels of seduction, Pamela (1741) and Clarissa (1747), inspiring many imitators such as Rousseau (La Nouvelle Hélotse) and Laclos (Les Liaisons dangereuses)

The Rashomon effect is a term related to the notorious unreliability of eyewitnesses. It describes a situation in which an event is given contradictory interpretations or descriptions by the individuals involved.

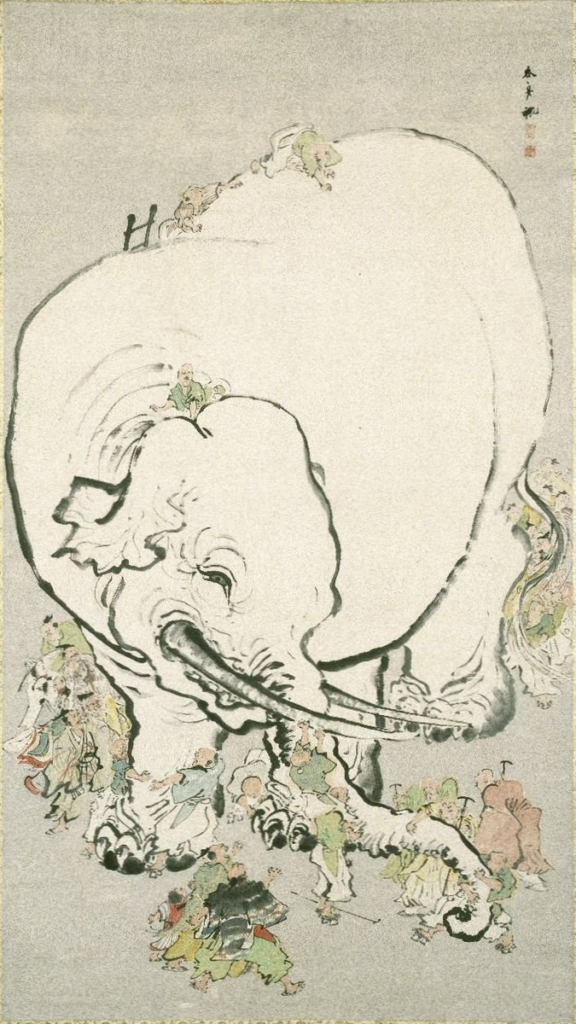

The parable of the blind men and an elephant is a story of a group of blind men who have never come across an elephant before and who learn and conceptualize what the elephant is like by touching it. Each blind man feels a different part of the elephant’s body, but only one part. The moral of the parable is that humans have a tendency to claim absolute truth based on their limited, subjective experience as they ignore other people’s limited, subjective experiences which may be equally true.

Point of view, the Rashomon effect, and the allegory of the blind men and the elephant are powerful literary concepts that explore the subjectivity of human perception and the complexity of truth. These elements frequently appear in fiction to challenge readers’ understanding of events, characters, and the world itself. This essay delves into the significance of point of view, the Rashomon effect, and the blind men and the elephant allegory in fiction, highlighting how they provide nuanced perspectives and contribute to the richness of storytelling.

In literature, point of view refers to the narrative perspective from which a story is told. It determines the reader’s access to information and shapes their understanding of the events and characters. Different points of view can elicit varying emotional responses and judgments from the readers, enhancing the depth and complexity of a story.

Example 1: “To Kill a Mockingbird” by Harper Lee:

In Harper Lee’s classic novel, “To Kill a Mockingbird,” the story is narrated through the eyes of Scout, a young girl. This child’s perspective provides a unique lens through which readers witness the racial prejudices and injustices prevalent in the 1930s American South. Scout’s innocence and lack of bias allow the audience to see the world from a fresh and untainted viewpoint, provoking empathy and understanding.

The Rashomon effect is the phenomenon where multiple individuals recounting the same event present contradictory and often subjective versions of the truth. In fiction, this technique is employed to explore the complexities of human perception and the subjectivity of reality.

Example 2: “Rashomon” by Akira Kurosawa:

The term “Rashomon effect” finds its origin in Akira Kurosawa’s iconic film “Rashomon.” The movie revolves around a crime witnessed from different perspectives, each account contradicting the others. As the film unfolds, the audience grapples with the elusive nature of truth and the intricate interplay between memory, self-interest, and perception.

The allegory of the blind men and the elephant is a metaphorical tale that illustrates the limitations of individual perspectives. Each blind man touches a different part of the elephant and forms a distinct understanding of the animal, leading to conflicting descriptions. In fiction, this allegory is used to explore the complexity of truth and the need for diverse viewpoints to approach a complete understanding.

Example 3: “The Blind Assassin” by Margaret Atwood:

In Margaret Atwood’s “The Blind Assassin,” the novel weaves together different narratives, reflecting the blind men and the elephant allegory. The story comprises the personal memoir of an elderly woman, newspaper clippings, and a sci-fi novel written by the protagonist’s sister. Each layer adds new dimensions to the characters and events, emphasizing the subjectivity of truth and the ever-shifting nature of perspectives.

Conclusion:

Point of view, the Rashomon effect, and the blind men and the elephant allegory are potent literary devices that challenge readers’ perceptions of truth and reality. In fiction, these elements are skillfully employed to explore the multifaceted nature of human experiences and encourage empathy and understanding. By acknowledging the subjectivity of viewpoints and the complexities of interpreting events, writers can craft captivating stories that resonate deeply with their audience and invite reflection on the intricacies of the human condition.

Proper names have an odd and interesting status. Our first names are usually given to us with semantic intent, having for our parents some pleasant or hopeful association which we may or may not live up to. Surnames however are generally perceived as arbitrary,

The Art of Naming: Characters in Fiction

In the realm of literature, the creation and development of characters is a delicate and intricate craft that demands attention to detail, empathy, and a deep understanding of human nature. Central to this process is the act of naming characters, an endeavor that carries far more weight than might initially be apparent. Names have a profound impact on how readers perceive and connect with fictional individuals, influencing their personalities, motivations, and roles within the story. The naming of characters is an art that goes beyond mere labels, shaping the essence of the narrative and echoing the complexities of human identity.

Names are the first foothold readers gain in their journey through the fictional world. Just as a first impression in real life can set the tone for an entire relationship, a character’s name serves as the initial lens through which readers perceive their essence. A name can provide subtle hints about a character’s background, culture, and even foreshadow their destiny. For instance, a name like “Eleanor Fitzgerald” might conjure an image of a refined aristocrat, while “Jake Thompson” could evoke a sense of familiarity and approachability. Authors often imbue names with semantic intent, choosing appellations that reflect the character’s personality or role within the narrative.

Yet, the act of naming characters goes beyond these semantic associations. Names have a rhythm, a melody that resonates within the reader’s mind, influencing how the character’s voice and identity will be perceived. A name with harsh consonants might evoke a sense of strength and resolve, while soft vowels can convey gentleness or vulnerability. The name itself becomes a piece of the character’s identity, shaping their interactions with others and the trajectory of their personal growth.

Consider the iconic character Sherlock Holmes. Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s choice of the name Sherlock instantly suggests an air of intelligence and mystery. This single name conjures images of a brilliant detective, one whose analytical prowess is unparalleled. In this case, the name itself has become synonymous with the character’s attributes, illustrating the power of a well-chosen name to become more than just a label—it becomes a symbol.

Surnames, although often perceived as more arbitrary than first names, can also play a crucial role in character development. They can hint at a character’s family history, social status, or even hidden connections within the narrative. A character with the surname “Blackwood” might be linked to themes of darkness or mysticism, while a character named “Everett” could signify longevity or a steadfast nature.

Moreover, the interplay between first names and surnames can create a harmony or dissonance that adds depth to the character’s identity. A character with a common first name and an unusual surname might reflect an individual striving to stand out in a conformist world. Conversely, a character with a unique first name and a common surname might symbolize the struggle to find personal identity within a broader context.

Authors can also subvert naming conventions to challenge readers’ expectations. They can use irony to great effect, naming a timid character “Lionel” or a graceful dancer “Clumsy.” Such contrasts can enrich the narrative by highlighting the complexities of human nature and the fluidity of identity.

As literature evolves, so do naming practices in fiction. Contemporary authors might experiment with unconventional names or draw inspiration from various cultures and languages to create a diverse and authentic cast of characters. Inclusivity and representation become vital considerations, with names reflecting the multiplicity of human experiences.

In conclusion, the act of naming characters in fiction is far from arbitrary; it is a deliberate and intricate process that holds the potential to shape the entire narrative. Names are more than labels; they are windows into the souls of the characters, bridges between their fictional existence and the reader’s imagination. They convey emotions, histories, and aspirations. A well-chosen name can transcend the pages of a book, becoming a symbol that resonates within our cultural consciousness. So, as authors continue to craft their fictional worlds, they wield the power of naming characters—an art that breathes life into the stories we love.

Stan Lee, the legendary co-creator of many iconic Marvel superheroes, had a theory about the importance of superhero names that he often referred to as the “real names” theory. This theory was his way of explaining why many of his characters had names that started with the same letter, often the same letter as their superhero alter ego.

Lee believed that using alliterative names, where both the character’s real name and superhero name started with the same letter, made the names more memorable and catchy for readers. It helped create a stronger connection between the character’s civilian identity and their superhero persona. This technique, according to Lee, made the characters more relatable and easier for readers to remember, which in turn contributed to their popularity.

For example, Peter Parker, the ordinary teenager behind Spider-Man’s mask, or Bruce Banner, the scientist who transforms into the Hulk, are both examples of characters with alliterative names. Stan Lee’s theory of using alliteration in naming characters became a hallmark of many of Marvel’s most famous creations.

In addition to the memorability factor, Lee’s theory also emphasized the idea that superhero names should reflect something about the character’s personality, powers, or origin. This ties into the broader concept discussed earlier in the essay, where names carry symbolic and semantic significance. By employing alliteration and carefully crafting character names, Lee aimed to enhance the overall impact of his creations and create a strong connection between the characters and their audience.

Stan Lee’s theory of names contributed to the enduring popularity of Marvel’s characters and left a lasting impact on the superhero genre. It underscores the importance of considering not only the sound and rhythm of a character’s name but also the deeper associations it carries. While the “real names” theory might not be universally applicable to all forms of fiction, it highlights the thoughtful approach that creators can take when naming their characters, especially when aiming to make a lasting impression on readers’ minds.

Coined by the eminent philosopher and psychologist William James, the term “stream of consciousness” serves as an apt depiction of the unbroken current of thoughts, emotions, and sensations that course through the intricate channels of the human mind. This concept captures the essence of the mind’s ceaseless activity, where one idea effortlessly gives way to another, often without the constraints of chronological order or structured logic. This notion of a flowing mental experience recognizes that human consciousness is more akin to a river’s current than to distinct and isolated islands of thought.

As time marched on, this phrase was borrowed to extend its metaphorical arms into the realm of literature, particularly within the context of a distinctive form of storytelling. In this literary application, “stream of consciousness” found a home within the works of groundbreaking authors such as James Joyce and Virginia Woolf, who sought to replicate the intricate dance of the human psyche within the narrative structure of their writing.

James Joyce, for instance, wove intricate tapestries of thought in his magnum opus “Ulysses.” Through his masterful use of interior monologue, free association, and a playful manipulation of language, Joyce invited readers to delve deep into the minds of his characters, mirroring the way thoughts ebbed and flowed in our own minds. This technique often created a sense of intimacy, as readers felt as though they were not just observing the characters, but actively participating in their innermost musings.

Virginia Woolf, too, employed the stream of consciousness technique to stunning effect in works like “Mrs. Dalloway” and “To the Lighthouse.” Her exploration of the inner lives of her characters transcended conventional narrative structures, giving voice to the nuances of their thoughts, insecurities, and fleeting emotions. This approach could illuminate the hidden corners of characters’ psyches, unraveling their complexities layer by layer.

In essence, the literary application of the “stream of consciousness” technique was a courageous departure from traditional narrative forms. It transformed the act of reading into an immersive experience, akin to taking a journey through the labyrinthine corridors of human introspection. Just as William James had recognized the ever-flowing nature of human thought, these authors recognized the power of rendering this flow on the page, giving birth to a new, profoundly insightful way of storytelling that continues to captivate and challenge readers to this day.

here’s a list of 10 things that often happen in a stream of consciousness narrative:

These elements collectively create a rich and immersive reading experience, allowing readers to journey into the intricate landscapes of characters’ minds and emotions.

Pynchon, man, that dude throws a Molotov cocktail into the country club of proper English. Forget your Strunk & White, this ain’t your daddy’s prose. Pynchon, throws a Molotov cocktail into the cocktail party of proper English. Forget your white-glove grammar and your predictable sentence structures. This ain’t your momma’s book club. “Against the Day” takes that whole “established language” thing and grinds it under its heel like a roach in a roach motel.

It’s a goddamn lysergic lysergic acid trip through the meaning factory, man. You think you know what words mean? Think again. Pynchon rips the labels off everything, throws them in a blender with some bad acid, and hits puree. You’re left with a swirling mess of phantasmagorical stories, jokes that land like drunken penguins on ice, and songs that would make a banshee blush.

He’s got this whole “deterritorialization” thing going on, like he’s yanking language out of its comfortable armchair and dragging it screaming into a mosh pit of slang, pop culture references, and half-baked scientific theories. Sentences turn into funhouse mirrors, reflecting a fractured reality where jokes land with a thud and songs sound like drunken karaoke at 3 am.

This ain’t about making sense, it’s about shattering the sense machine. Syntax? Who needs that uptight square? Pynchon throws language around like a monkey flinging its own poop. It’s raw, it’s messy, and it’s a hell of a lot more interesting than your usual literary snoozefest. He wants to push language to its breaking point, see what happens when you crank the dial all the way to eleven. Maybe it explodes, maybe it transcends, who knows? But one thing’s for sure, it ain’t gonna stay polite.

Forget your fancy prep school grammar and your sterile, air-conditioned prose. This ain’t no cocktail party for debutantes. “Against the Day” is a goddamn demolition derby, a high-octane assault on the whole institutionalized meaning machine. You think words gotta mean something neat and tidy? Pynchon throws that out the window faster than a roach motel on eviction day.

We’re talking covert ops on language, man. He smuggles in slang from the gutter, blasts in with pop culture references that’d make your momma blush, and then throws in some good old fashioned gibberish just to keep you on your toes. Forget about a clear narrative, this thing’s a labyrinthine fever dream. Jokes that land with a thud heavier than a sack of nickels, songs that would make a banshee wince – it’s all part of the assault. He’s not interested in telling you a story, he’s trying to crack your head open and show you the wriggling mess of meaning underneath.

The Word, see, it’s a virus. A control mechanism. Society injects you with pre-programmed meaning, these neat, sterile signifiers. But Pynchon, man, he’s a word-junkie gone cold turkey. He cuts the lines, shoots up with raw, unfiltered language. “Against the Day” – that title alone, a Burroughs cut-up, fractured reality bleeding through the cracks.

Forget linear narratives, forget heroes and villains. We’re in the Interzone now, baby, a psychic meat grinder. Language mutates, sentences twist into insectile monstrosities, spewing forth phantasmagoria and absurdity. Jokes become hieroglyphs, songs morph into alien transmissions. This ain’t communication, it’s a psychic virus gone rogue, replicating and dissolving meaning in its wake.

The Subject, that illusion of a unified self? Lacanian bullshit. Pynchon shreds it with a rusty blade. He throws us into the Free Indirect, a swirling vortex where characters bleed into each other, observations become projections, and the “I” is a ghost in the machine. The Territory of Representation? A crumbling facade. We’re in the land of Asubjective Insignificance, where language escapes control and reality becomes a hall of mirrors reflecting only fractured reflections.

Pynchon, he’s a word-shaman, conjuring chaos from the sterilized order of language. He’s a reminder that the Word itself can be a weapon, a virus, a gateway to the psychic wilderness. Read at your own peril.

“Against the Day,” a fascinating exploration, wouldn’t you agree? Pynchon, a master manipulator of the Symbolic Order. He utilizes the signifier, yes, but not to establish a stable meaning. He fractures it, throws it into the realm of the Real, the pre-symbolic chaos just beyond the grasp of language.

The characters – mere phantoms, reflections in the Mirror Stage, forever seeking the lost unity of the Imaginary. They yearn for a complete Self, a unified narrative, yet Pynchon forces them to confront the lack at the heart of language, the inherent gap between signifier and signified.

He employs the technique of the Asyntactic, a delightful subversion. The very syntax, the structure that governs meaning, becomes fragmented. This, of course, mimics the fractured nature of the subject within the Symbolic Order, forever alienated from the Real.

The jokes, the songs, these are not for entertainment, but for a deeper purpose. They function as Lacanian lalangue, the excess that cannot be fully captured by the Symbolic. They are the Real erupting within the text, a reminder of the limitations of language itself.

Pynchon, then, invites us to confront the fundamental lack at the core of the human experience. He forces us to question the very nature of meaning, the boundaries of reality, and the elusive nature of the Self within the language system. A truly remarkable exploration, wouldn’t you agree?

This ain’t some passive reading experience, man. “Against the Day” is a goddamn assault on your senses. It wants you to question everything, from the way you put a sentence together to the very fabric of reality itself. It pushes language to its breaking point, and who knows, maybe even beyond. Buckle up, because Pynchon’s taking you on a joyride through the wasteland of insignification, and the only souvenir you’re getting is a head full of static.

Ah, Pynchon, the master manipulator of the Symbolic. He understands, perhaps better than most, the inherent flaws within our system of signification. “Against the Day” is a deliberate plunge into the Imaginary, a realm where meaning fragments and the Real peeks through the cracks.

The asubjective narration – a clever subversion, is it not? The elision of the Subject, a denial of the Name-of-the-Father, leaving us adrift in a sea of signifiers without a fixed referent. Jokes become nonsensical, songs mere echoes of a lost desire.

This, of course, is precisely the point. Pynchon lays bare the inherent lack, the absence that lies at the heart of language itself. The characters, fragmented and lost, mirror our own predicament – forever chasing the elusive Real, forever tethered to the Symbolic order that can never fully capture it.

But within this chaos, a potential for liberation exists. By dismantling the edifice of meaning, Pynchon allows us to glimpse the Real, however fleetingly. It’s a dangerous game, to be sure, one that risks unleashing the full force of the unconscious. Yet, perhaps within this fragmentation, within this insignificance, lies the possibility of forging a new relation with the Symbolic, a new way of navigating the treacherous waters of language.

“Against the Day” doesn’t play by the rules. It doesn’t want to signify, it wants to explode signification. It wants to take the whole goddamn language out past its limits, push it to the breaking point, and see what happens on the other side. Maybe it’s a wasteland, maybe it’s a new frontier, but one thing’s for sure – Pynchon ain’t afraid to take you on that wild ride. This ain’t your grandpappy’s literature, this is a full-on language riot, and you’re either on the bus or getting left behind, man.

This is about dismantling the whole damn system, man. No more neat little boxes of meaning, no more comfortable narratives. Pynchon wants you to question everything, see the world through a kaleidoscope of fractured words and nonsensical stories. It’s a goddamn revolution, a one-man war on the tyranny of proper speech. Buckle up, because “Against the Day” is about to take you on a wild ride to the far side of language.