A Radical Simplicity

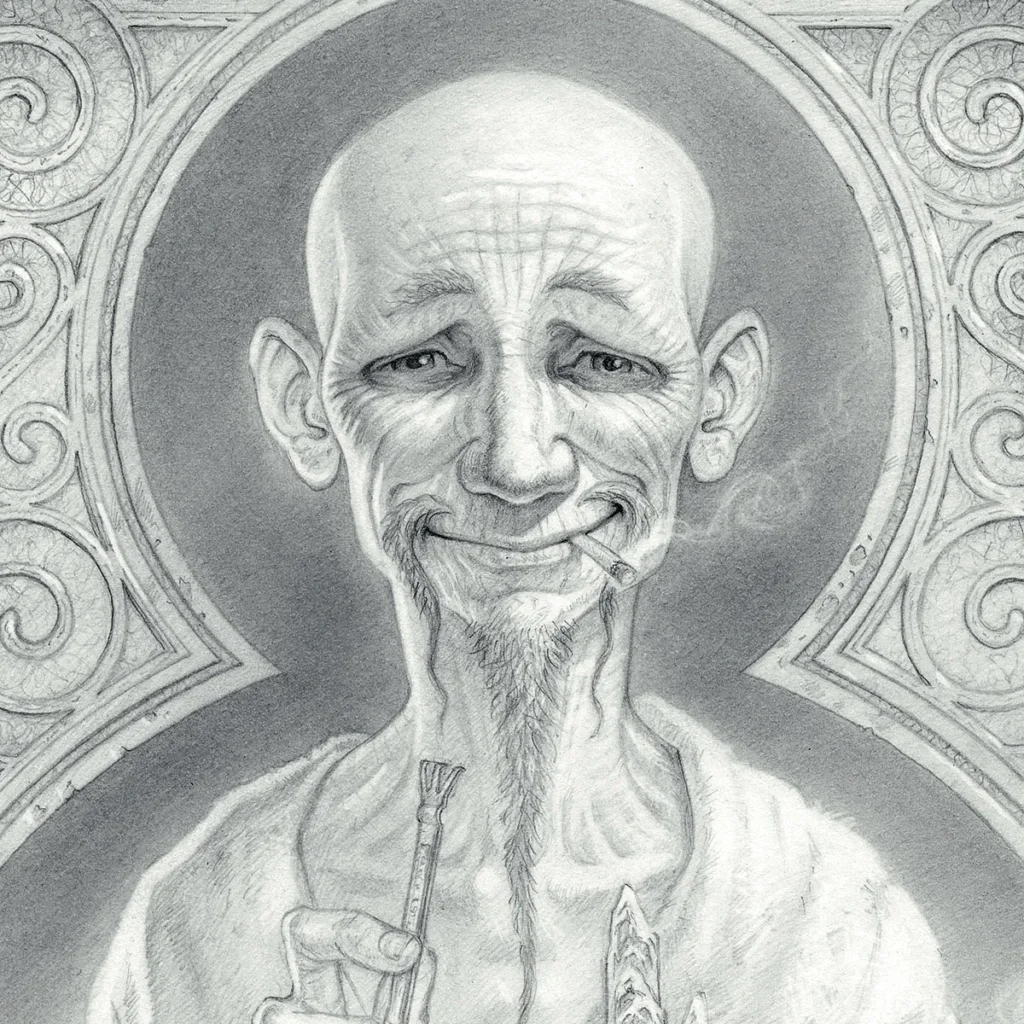

Terry Pratchett’s Lu-Tze, the humble sweeper-monk, embodies a philosophy that transcends the binaries of control and chaos, order and entropy. His approach echoes the Taoist principle of wu wei—effortless action—where effectiveness arises not from force or rigid doctrine, but from alignment with the natural flow of things. In a world where systems demand either compliance or rebellion, Lu-Tze’s quiet labor becomes a subversion of both. He sweeps floors, tends gardens, and occasionally nudges history with a well-timed proverb, all while maintaining an almost Zen-like detachment. This isn’t apathy; it’s a deliberate refusal to be ensnared by the narratives that trap others.

Where Jeremy Clockson is a being of precision, of engineered inevitability, Lu-Tze is improvisation wearing a broom. He acts, but never hurries. He intervenes, but rarely directly. He knows when to do nothing—not out of laziness, but because doing nothing is sometimes the most powerful move on the board. This is wu wei: not passivity, but attunement. Not resistance, but redirection.

Lu-Tze’s true rebellion is his refusal to play the game on the game’s terms. In a monastery of time-obsessed monks and obsessive administrators, he becomes a kind of counter-temporal agent. His toolkit isn’t quantum precision—it’s tea, footnotes, and aphorisms. He smuggles agency into a world obsessed with schedules. He practices radical patience in an age of urgency.

Importantly, wu wei does not mean disengagement from the world. On the contrary: it demands deep presence. But presence without domination. Lu-Tze notices—and this makes him dangerous. He is underestimated precisely because he refuses to self-mythologize. He does not posture. He sweeps. And in that sweeping, he rewrites the future.

Lu-Tze’s simplicity isn’t just spiritual—it’s political. In a world increasingly obsessed with spectacle and optimization, he embodies a slow refusal. His sweeping is a practice of soft power, a kind of monkish mutual aid. It doesn’t scale. It doesn’t trend. But it works. And that’s why the Auditors hate him. He cannot be predicted. He cannot be optimized. He is the chaotic good of quiet maintenance.

And while characters like Lobsang enact the tension between order and soul, Lu-Tze offers a third path: the invisible art of keeping things just functional enough not to collapse. He’s not the hero. He’s the janitor of the sacred. The clock ticks because he keeps the dust off the gears.

In terms of art and meaning-making, Lu-Tze is the analog craftsperson in the back room. The slow artist who whittles spoons. The poet who doesn’t publish. He doesn’t need applause. He just needs the floor to be clean.

Marx, Zen, and the Clock as Capital

When the Abbot instructs Lu‑Tze to “stop the clock,” the order resonates beyond plot. The clock—especially the perfect one Jeremy Clockson builds under the Auditors’ influence—isn’t just a timepiece; it’s the fantasy of total control. In Marxist terms, it’s capital’s dream object: pure quantification, the commodification of time itself. No deviation, no subjective experience, just value measured in ticks and tocks.

Lu‑Tze is the anti-capitalist, anti-bureaucratic Zen Marxist janitor. He doesn’t wage war against the machine—he sweeps around it, confounds it, slips through its gears. His proverbs, riddles, and broom are more subversive than any manifesto. Like a Zen koan, he can’t be neatly interpreted, and that’s the point. He’s not here to solve the system; he’s here to remind us it was never sacred to begin with.

Marx wrote that under capitalism, even time becomes alienated—we no longer live in it, we sell it. Lu‑Tze refuses that paradigm. Ask his job, and he says, “I’m just the sweeper.” Which is to say: I exist outside your categories. He’s the embodiment of kairos—opportune time—against the capitalist worship of chronos—measurable time.

Lobsang and the Split Self

Lobsang Ludd, apprentice monk and living incarnation of Time itself, is where the grand cosmic argument becomes achingly personal. His story is not just the tension between past and future, or between chaos and order—it’s the fracture at the heart of the modern self. Lobsang is a contradiction made flesh: half-human, half-myth, half-clock. His very existence is a split screen—on one side, the warm, impulsive, half-smiling boy who steals apples and tells jokes; on the other, Jeremy Clockson, the ultra-competent craftsman of inevitability, built to measure, built to obey.

This isn’t just narrative cleverness—it’s a diagnosis. Lobsang is the embodiment of the contemporary condition: a being caught between the speed of machines and the slowness of meaning. Between the spreadsheet and the dream. He is what happens when the soul tries to survive under metrics. When intuition is pressed into a uniform and told to meet deadlines.

Lu-Tze, the sweeper monk, sees this. And crucially, he doesn’t try to resolve it with doctrine or logic. He doesn’t lecture. He doesn’t offer a syllabus. Instead, he teaches Lobsang with confusion. With humor. With badly-timed jokes and inexplicable errands. His method is methodlessness: pedagogy by surprise. He introduces Lobsang to the art of the sidelong glance, the subtextual lesson, the broomstroke that changes history.

This is not revolution in the industrial sense—there are no manifestos, no barricades. It’s resistance by living otherwise. To take joy in something unmeasurable. To make tea slowly. To laugh at a pun. These are not small things. In a world obsessed with precision, a bowl of noodles can be an act of defiance. A quiet joke can derail a deterministic future.

Lu-Tze teaches Lobsang that time is not a prison to be maintained but a river to be floated on, or sometimes stepped out of entirely. In doing so, he reframes the problem. The question is no longer how to perfect time, but how to inhabit it. How to dwell in it, care for it, misuse it even—and in doing so, reclaim it.

Lobsang’s journey, then, is not to choose between Jeremy and himself, but to integrate the two. To become both clock and cloud. Both structure and soul. This synthesis—impossible, absurd, necessary—is the real victory. Because the enemy is not order, nor even chaos, but the idea that one must erase the other to function.

In a culture that demands specialization and speed, Lobsang learns instead to be whole. Not perfect, not optimized—just whole. That, in the end, is what saves the world: not stopping time, not preserving it, but allowing it to contain multitudes.

Stopping the clock isn’t about breaking time—it’s about restoring it. Thief of Time argues that history isn’t a riddle to be solved or a path to be completed. It’s a garden. Messy, uneven, and alive. And someone, quietly, has to sweep the paths.

THE AUDITORS

The Auditors in Thief of Time are terrifying from central casting not because they’re evil in the traditional sense, but because they’re pure function. They’re obsessed with eliminating chaos, optimizing everything, and making the universe neat, clean, and predictable. In that way, they’re like a cosmic version of the “paperclip maximizer” thought experiment—an AI that pursues its goal with such blind efficiency that it destroys everything else in the process.

They don’t hate humanity. They just see people as messy. Irrational. Inefficient. Too unpredictable to fit into a perfectly ordered system. So their solution is to remove the mess entirely—by removing us.

This is what makes them funny. They’re not monsters in jackboots. They’re not driven by hatred. They’re driven by logic—cold, bloodless logic. They’re what happens when you take the tools of technocratic liberalism—optimization, system design, rational planning—and strip away any empathy, humility, or tolerance for contradiction. What’s left is a mindset that wants the world to be smooth, silent, and sterile.

In that sense, the Auditors are like the evil twin of the liberal world order: not violent tyrants, but clean managers of doom. They don’t scream. They just delete.

Now contrast that with the monks. They’re flawed, yes—but they still tolerate mess. They try to keep time flowing properly, understanding it’s a balancing act, not a solved equation. They’re like caretakers of a delicate ecosystem rather than engineers of a perfect machine.

But even they fall short. Because they, too, come from a worldview that believes in managing history—as if history were something you could balance forever. And when time begins to break apart, their calm detachment becomes paralysis.

Only Lu-Tze can respond—not because he’s stronger, but because he’s freer. He doesn’t buy into the idea that the world can be perfected. He doesn’t try to control history. He just shows up, broom in hand, and starts sweeping. He accepts the chaos. He works within it. He does the job, with humility and humor.

In an age where both authoritarian systems and well-meaning managerial ones are failing—where optimization itself becomes a form of violence—Lu-Tze represents something radically different. Not a new system. Not a better theory. Just a person doing honest work without illusions of control.

In refusing the ego’s demand to be seen, branded, optimized. He chooses simple labor over a life of performance. He holds on to his mind, even as he gives his body to the work.

Because in Lu-Tze’s quiet refusal to turn his soul into a product, there’s a radical dignity—one that many in modern, “creative” industries have traded away in exchange for LinkedIn clout or “personal branding.” In this light, sweeping isn’t just a job. It’s a form of resistance. A refusal to be consumed by the economy of self-exploitation.

This continues in a sort of, you know, Machiavellian way—like somewhere back in the boardrooms of capitalism in the 1950s, someone realized a terrible truth: if we only work them physically, they still have their minds to themselves. They can think. They can dissent. They can dream. But if we own their minds—if we capture their attention, their imagination, their very sense of self—we won’t need to police them. They’ll police themselves.

So the strategy shifts. The new labor isn’t just lifting or building; it’s aligning yourself with corporate values, being “passionate” about KPIs, injecting your personality into your emails. The worker becomes the product. The sellable thing is no longer what you do, but who you are—or at least, who you pretend to be.

And here, again, Lu-Tze sweeps in—not as a guru, but as a quiet rebuke. He sweeps the floor, not his soul. He gives the world his labor, but never his mind. In this age where rebellion looks like burnout and docility looks like ambition, the old monk with a broom might be the last revolutionary.

The strategy doesn’t just shape the workplace, it colonizes the imagination. It bleeds directly into our storytelling, especially in Hollywood and Netflix-era content, where the protagonist has subtly shifted. The old hero archetypes—the farmer called to greatness, the dreamer resisting the empire—have been replaced by agents, analysts, special forces vets, or start-up founders. These are people who already belong to systems of control. They’re not breaking out—they’re maintaining order, upholding protocol, or innovating inside frameworks that already exist.

Even when they “rebel,” it’s within limits that flatter the machine: the FBI agent who goes rogue to save the world still proves the FBI was right to hire her. The ex-military man haunted by war trauma still resolves it through more violence, but now “on his own terms.” The tech bro turned savior doesn’t overthrow the system—he just upgrades it. These characters don’t escape the algorithm—they are the algorithm’s fantasy of rebellion. Branded authenticity.

It’s all part of that same Machiavellian realization: don’t just command people—make them want it. Don’t suppress their individuality—monetize it. The contemporary protagonist is no longer a mirror to our struggles; he’s a recruiting poster. He performs freedom while embodying control. And in that sense, these narratives are the cultural arm of the same logic that gave us the corporate wellness seminar, the “personal brand,” and the company Slack channel that feels like a dystopian high school.

This is why someone like Lu-Tze matters so much. He isn’t optimized. He isn’t curated. He’s not a brand. He’s just a guy doing what needs doing, outside the spectacle. And that’s why he’s radical.

What we’re seeing is the deep saturation of ideology—not in the old sense of state propaganda or brute censorship, but in a much more insidious form: narrative capture. Capital doesn’t want to stop stories—it wants to own them. And what better way than to write the protagonist as someone whose only real power is to work better within the system?

So rebellion becomes a product feature. The hacker is now a start-up founder. The punk is an influencer. The rogue cop is the best cop. The spy questions authority, but only to save the world on its terms. It’s not that culture stopped telling stories of resistance—it’s that resistance got turned into a genre with a three-act structure and a Disney+ spin-off.

In this environment, every main character is either trauma-forged or professionally competent. They have to be broken, but in a narratively useful way. And most importantly, they must be redeemable by the system. Their inner conflict resolves when they get their badge back, their startup funded, or their team reassembled.

Catharsis becomes compliance.

Now contrast that with Lu-Tze: the sweeper monk who doesn’t seek attention, who dodges the spotlight, who doesn’t want to be the main character. He refuses the call—not out of fear, but out of understanding. He knows that history is made by people who don’t try to control it. He sweeps. He listens. He waits. And when he acts, he does so without drama.

In a world that’s turned “authenticity” into a monetizable trait and main characters into brand extensions, Lu-Tze is dangerous. He’s not “off the grid” in a performative way—he’s simply free. Free in the oldest and strangest sense: detached, modest, impossible to incentivize. He’s immune to optimization.

This is why Pratchett’s world hits harder now than it did when he wrote it. He saw what was coming—not just the collapse of systems, but the rise of counterfeit freedom, scripted rebellion, and algorithmic individuality. And he offered something better: humility, absurdity, action without ego.

What Pratchett sketches in Thief of Time is not just a witty fantasy about monks tinkering with clocks—it’s a profound meditation on history, time, and agency. If Fukuyama’s “End of History” imagines a world where liberal democracy and capitalism have resolved all major ideological conflicts, then time, in that schema, becomes flat and singular: we’ve arrived, the story is over, and all that remains is management.

This is the world the Auditors dream of. They abhor the messiness of human narratives and long to impose an eternal present, scrubbed clean of desire, error, and surprise. In a way, they are the spiritual children of the End of History thesis—believers in order for its own sake, where time is reduced to quantifiable ticks, a perfect loop with no deviation.

But Pratchett gives us another vision in the Monks of Time. Unlike the Auditors, the Monks understand that time is not a monolith. It is lived unevenly across the world. A grieving village needs more time. A battlefield needs to pause. A moment of epiphany must stretch beyond the confines of the clock. Their work is to redistribute time, not in the cold logic of administration, but in the spirit of care and responsiveness. They are not trying to stop history, nor complete it—they’re trying to keep it humane.

And that is why Lu‑Tze, the humble sweeper, who operates in the cracks of the grand system, understands that the world is not governed by doctrines or end-states, but by small acts of compassion, disruption, and patience. While the Abbot contemplates the eternal in infant form, Lu‑Tze walks the earth, subtly correcting course, never seeking credit. He embodies an ancient truth found in both Zen koans and Marxist critique: that true understanding isn’t about controlling history, but about living rightly within it—even if that means sweeping floors and defying fate in small, absurd, very human ways.

In this framework, Thief of Time becomes a powerful rebuttal to any notion of temporal finality. It’s not just that history hasn’t ended—it’s that history, like time itself, must remain alive, messy, and open to revision.