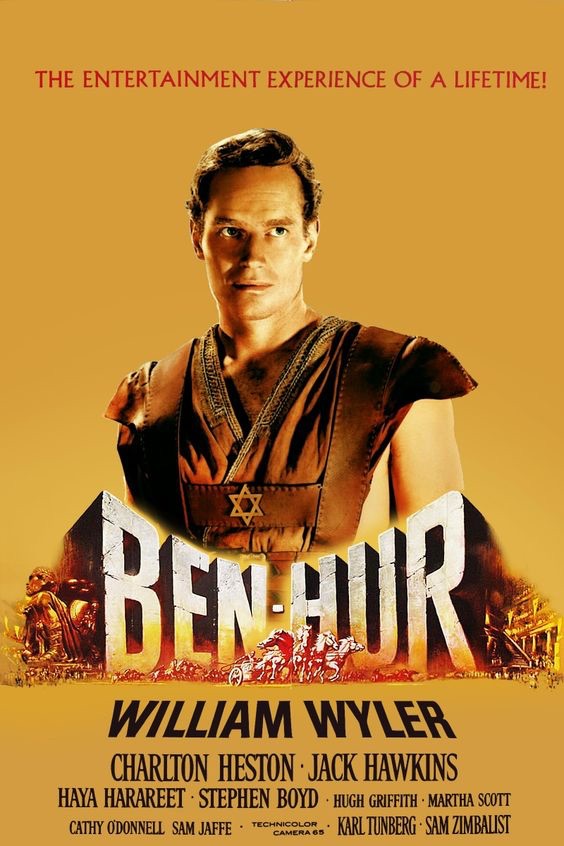

The brilliance of Ben-Hur, and its simultaneous duplicity, lies in its quiet realignment of cultural identity for the sake of narrative expedience. Judah Ben-Hur, ostensibly a Middle Eastern Jew in the Roman province of Judea, is unmistakably reframed as an Ashkenazi Jew—a Jewishness that is Western, assimilable, and, crucially, palatable to mid-century American audiences. Charlton Heston’s towering Nordic features and clipped diction render Judah less a Judean patriot and more a prototypical American man of destiny, stranded inconveniently in an antique world. This is not an accident; it is a choice—a calculated sleight of hand.

The adoption of the name Arius is no small symbolic act. By being subsumed into the Roman patrician elite, Judah casts off his provincial origins like a beggar discarding his rags. To Rome, he ceases to be an outsider—a Jew—and becomes instead a version of himself that the empire can tolerate: a cosmopolitan inheritor of power. He is a Jew only in so far as it facilitates the story’s moral arc, his identity purified of the inconvenient specifics of Judean culture. This transformation reflects not just Hollywood’s discomfort with depicting the true otherness of ancient Jewishness, but its preference for Westernizing its heroes to make their triumphs universal.

This is the dog whistle of identity in Ben-Hur. Judah’s ascension within Rome is not just a personal victory but a conversion—a metaphysical endorsement of Rome’s civilizing mission. The implicit message: true Jewishness is only acceptable when it ceases to be distinct, when it is grafted onto the trunk of Western culture. Judah’s final absolution, kneeling at the cross, is less about the salvation of a man than the quiet erasure of his heritage. He is no longer a Jew, nor even a Roman; he becomes something more familiar to the 1959 audience: a Christian.

Gore Vidal was brought in to revise the Ben-Hur screenplay, and his sharp wit and skill with innuendo elevated the material far beyond the typical Roman spectacle. Vidal made implicit themes explicit, particularly in the dynamic between Judah Ben-Hur and Messala. He deliberately framed their relationship as one with a deeply intimate past, transforming Messala’s betrayal into a personal and emotional rupture rather than a purely political one. This subtext added a layer of sophistication and complexity, turning Ben-Hur into a reflection on identity, power, and forbidden desire, rather than just another grandiose biblical epic.

At the same time, Vidal infused the film with his own critique of hypocrisy. The Rome of Ben-Hur, sanitized for mid-century consumption, is a far cry from the violent, chaotic empire Vidal explored in his own writings. Yet it unmistakably mirrors Eisenhower’s America: imperial yet righteous, brutal yet self-proclaimed benevolent. Judah’s journey embodies the ideological transformation Hollywood often demanded of its Jewish characters—placing them at the center of grand narratives of empire while simultaneously stripping their identity of its troubling particularities.

The gradation of Jewishness in Hollywood epics becomes a dance of acceptable assimilation. Middle Eastern Jews—unruly, provincial, overtly tied to the land—are rarely represented except as foils or obstacles. Ashkenazi Jews, with their European lineage, occupy the middle ground: able to transcend their origins, provided they shed their specificities. And at the pinnacle is the Christianized Jew, who triumphs by stepping fully into the universalizing embrace of Western civilization. Judah Ben-Hur’s story, then, is not just one of revenge and redemption, but of quiet cultural conquest.

Hollywood, we might note with a sardonic smirk, has always preferred its Jews Europeanized and its saviors Romanized. In this way, the cinema becomes less a temple of storytelling and more a house of mirrors, endlessly reflecting the anxieties of its creators.

HOUSE OF MIRRORS

In Ben-Hur, as in so many epics of the era, we are confronted not with history but with myth—specifically, the myth of America as a reluctant, benevolent superpower. By 1959, the United States was no longer an isolationist republic but the torchbearer of Western civilization, standing vigilant against the twin specters of godless Communism and decolonial unrest. And yet, the uneasy conscience of empire-making seeped into these films in ways their creators could not entirely control.

Take, for instance, the Romans of Ben-Hur. They are ostensibly the villains, decadent and cruel, presiding over their subjects with an iron fist. But look closer, and you’ll see their resemblance to a certain other global hegemon: their technological prowess, their sprawling reach, their smug conviction that their way of life is the pinnacle of human achievement. And yet, for all their might, the Romans are hollow, their society already in decline. The message, whether intentional or not, is clear: America, beware. Empires crumble under the weight of their own contradictions.

And what of the Arabs, those swarthy figures from central casting who populate the background of Ben-Hur and countless other films of the era? They are either exoticized as noble savages or reduced to comic relief, their humanity flattened into caricature. These portrayals were not merely lazy but ideological, reinforcing the idea of the Middle East as a backward region in need of Western intervention—a narrative that dovetailed neatly with America’s burgeoning interest in the region’s oil reserves. The Arabs in Ben-Hur are not real people; they are a pretext, a justification for the West’s paternalistic gaze.

Then there is the film’s infamous subtext, the simmering tension between Judah Ben-Hur and Messala, which Vidal himself gleefully claimed credit for. Here we find another reflection in the House of Mirrors: the unspoken queerness that permeates so many of these epics, lurking just beneath the surface like a whispered secret. The relationship between Judah and Messala crackles with a fervor that transcends friendship, yet the film cannot name it for what it is. To do so would be unthinkable in 1959, an era defined by McCarthyite purges and the Lavender Scare. Instead, their bond is sublimated into rivalry, their love transformed into hatred, a tragic casualty of a culture too fearful to confront itself.

And then, of course, there is the bomb. The specter of nuclear annihilation looms large over every frame of Ben-Hur, though it is never mentioned. The chariot race, with its thunderous violence and apocalyptic energy, is a microcosm of the Cold War itself: a contest of wills in which there can be only one victor, and the stakes are nothing less than the survival of civilization. The crucifixion scene, with its somber skies and anguished cries, feels less like a historical reenactment and more like a prophecy—a reminder that humanity’s greatest threat is not external but internal, the darkness within.

In the end, Ben-Hur is less a story of redemption than a reflection of America’s contradictions: its yearning for moral clarity and its complicity in imperial violence, its embrace of progress and its terror of change, its belief in its own exceptionalism and its gnawing fear of decline. The House of Mirrors offers no escape, only endless refractions of the same uncomfortable truths. And like Judah Ben-Hur, we find ourselves racing in circles, searching for salvation in a world that refuses to give it.

If Vidal were here, he might chuckle at the absurdity of it all—the grandiosity, the self-deception, the unspoken truths flickering on the edges of the frame. And then he would turn back to the mirror, not to admire himself, but to remind us that the reflection is always more revealing than the image we wish to project.

Ah, indeed—ultimately, aren’t we all a bit Ben-Hur? Princes in our own minds, parading through life with the polished regalia of self-importance, only to find ourselves stripped bare, like Judah, of the very identity we so carefully cultivated. Forced to manufacture something new, something more acceptable, as the world pulls at us from every direction, demanding that we play our part in the grand spectacle of existence. This is the cruel joke that life plays on us all. We spend our youth pretending to be royalty, wrapped in the mythologies we inherit, and by middle age, if we’re fortunate, we realize we are but actors on a stage, manipulating our own masks to survive.

It’s the great tragedy of the human condition—this ceaseless reinvention. We wear the identities others give us, like Roman togas, snug and suffocating, and then, when it suits us, we strip them off and try to emerge as something more noble, more pure. But we cannot escape the deep, existential tension between who we are and who we think we ought to be. The empire, in this case, isn’t just Rome or America—it’s the vast machinery of social expectation, culture, history, and even our own illusions, grinding us into shapes that feel more comfortable, but never quite real.

What Vidal would gleefully point out is the deep hypocrisy at the heart of this process. We, like Judah, inherit a world that demands we embrace its imperialistic vision: that we are conquerors, masters of our own fate, and yet we are constantly bound by the very chains we claim to have broken. We dress ourselves in the armor of success, of identity, and yet, just as Ben-Hur strips away the layers of Roman civility to reveal the brutal core beneath, our manufactured selves are eventually undone by the contradictions within. No amount of polished ambition, no matter how grand our chariot race or how lofty our cross, will absolve us of the deeper, unspoken truths we are too terrified to face.

What Vidal would savor, in his signature style, is the delicious irony: we all become, in our way, “Romans”—empire-builders without the empire, strutting as if we are masters of fate, only to be confronted, as Judah is, with the realization that we are nothing more than our particular cultural constructions, endlessly colliding with each other. Ben-Hur is not merely a story of redemption; it is the story of the human condition itself. Every empire, every identity we forge is, in the end, just another layer of makeup on the face of a person who cannot escape the fact of being mortal, subject to time and decay. Yet, like Judah, we keep racing, never realizing that the prize was always a reflection of our own constructed desires—desires that, like the empire itself, are destined to crumble.