There is paradox with Paul McCartney, the melodic genius, the Beatle who could conjure pop perfection with the ease of a magician pulling rabbits from a hat, is at his most compelling not when he is in control, but when he is out of control. Or, more precisely, when he is challenged, when his polished instincts are disrupted by the intrusion of another’s voice.

To understand the difference between control and constraint is to grapple with a fundamental tension in human creativity, agency, and systems design. Both concepts involve the regulation of behavior or processes, but they operate in fundamentally different ways and produce different outcomes. Control is about imposing order from the outside, while constraint is about shaping possibilities from within. Let us unpack this distinction further, using examples from art, philosophy, and systems theory to illuminate the dialectical relationship between the two.

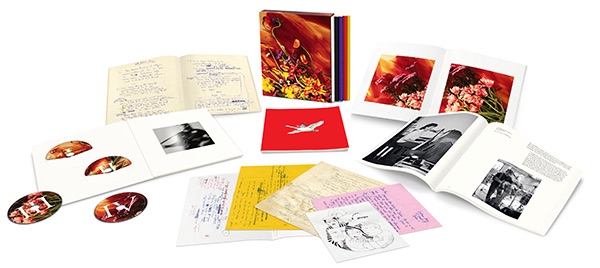

Listening to the Flowers in the Dirt special edition, one cannot escape the specter of George Harrison’s sardonic critique of McCartney’s saccharine tendencies in “Savoy Truffle”: “You know that what you eat you are, but what is sweet now, turns so sour.” McCartney’s solo work, for all its brilliance, often veers into the realm of the too perfect, the too sweet. But here, in the raw, unfinished demos of Flowers in the Dirt, we encounter a different McCartney—a McCartney who is not merely producing, but sparring. And who better to play the role of the sparring partner than Elvis Costello, the punk-inflected bard of bitterness and wit?

What stands out most in these sessions is how much the McCartney-Costello partnership elevated the work. Their collaboration wasn’t just transactional; it was symbiotic. While most of the songs remain unmistakably McCartney’s, Costello’s fingerprints—his rawness, edge, and knack for wordplay—are all over them. He wasn’t afraid to push McCartney, and it shows in tracks like the original version of “My Brave Face” or the unreleased demo versions of “The Lovers That Never Were.”

The difference here? Costello was a sparring partner, not a producer. A producer usually shapes the sound (exceptions galore, I know); a sparring partner shapes the ideas. The former can often polish things to a sheen that’s a little too perfect, but the latter challenges the artist, forces them to dig deeper, and exposes the creative tension that makes the music resonate.

Control is the attempt to dictate outcomes, to eliminate uncertainty, and to impose a predetermined order on a system or process. It is rooted in the desire for mastery, for predictability, for the elimination of chaos. In the realm of creativity, control often manifests as an overbearing producer, a rigid set of rules, or an artist’s own perfectionism. The problem with control is that it tends to stifle spontaneity, suppress emergence, and reduce complexity to simplicity.

The Illusion of Unbridled Freedom:

Creativity’s paradox lies in its reliance on constraint, not boundless freedom, to spark revolutionary breakthroughs. This is no abstract theory—it pulses through the work of Paul McCartney and countless artists. True creative potency arises not from untamed chaos but from obstacles that force adaptation, evolution, and self-transcendence.

The myth of creativity thriving in a vacuum—a bourgeois fantasy—ignores the material realities of art. Creativity is always entangled with constraints: economic, social, historical, psychological. The challenge is not to erase these limits but to weaponize them as catalysts.

Take McCartney’s career. His iconic work with The Beatles, Wings, and solo emerged from a dialectic between freedom and limitation. Early Beatles albums were shaped by studio tech boundaries, market demands, and interpersonal friction. Yet these very constraints fueled experimentation, birthing new forms of expression within narrow margins.

Control, in contrast, suffocates. A producer micromanaging tempo, instrumentation, or emotion might achieve technical perfection but drains music of its raw vitality. This mirrors Michel Foucault’s “disciplinary power”—top-down hierarchies that enforce compliance, breeding rigidity. Overcontrolled systems (ecosystems, artistic processes) grow fragile; constraints, however, foster resilience. Natural limits—predators, resources, climate—allow adaptation. Similarly, creative constraints act as internalized guardrails, channeling innovation rather than dictating outcomes.

The McCartney-Costello collaboration epitomizes this dynamic. Costello wasn’t a polish-obsessed producer but a provocateur injecting punk grit into McCartney’s melodic instincts. Their friction birthed a Hegelian synthesis: McCartney’s sentimentality tempered by Costello’s edge, elevating both.

This dialectic is foundational to McCartney’s legacy. With The Beatles, Lennon’s irreverence clashed with his melodic precision; George Martin’s production framed his creativity within enabling structures. In Flowers in the Dirt, Costello became the “sparring partner”—not smoothing edges but sharpening them through creative antagonism.

Such tension mirrors formal constraints in poetry: a sonnet’s 14-line straitjacket births profound emotion by forcing concision. Constraints aren’t shackles but conditions for possibility, what Deleuze called “immanent forces”—boundaries from which the new emerges.

The Flowers in the Dirt demos embody this ethos: raw, unfinished, crackling with live-wire energy. Their power lies not in polish but in process—proof that creativity thrives when pressed against limits, not coddled by false freedom.

The Role of the Sparring Partner: Constraint Without Control:

The sparring partner—whether a collaborator, critic, or conceptual foil—serves as a living constraint, injecting friction into creativity’s flow. In Flowers in the Dirt, Elvis Costello embodied this role, his punk-infused rawness clashing with McCartney’s polished melodic sensibilities. Rather than dictating terms, Costello’s presence destabilized McCartney’s habits, pushing him toward uncharted lyrical and musical terrain.

Unlike a controlling producer who micromanages outcomes, the sparring partner operates as a provocateur of limits. They disrupt complacency, forcing the artist to confront their own tendencies. Costello’s biting wordplay and rejection of sentimentality, for instance, acted not as shackles but as creative resistance—a counterweight that compelled McCartney to refine, adapt, and hybridize. The result was emergent alchemy: a fusion of McCartney’s lush melodicism and Costello’s gritty edge, yielding work that transcended either artist’s solo output.

This dynamic mirrors broader creative truths. Consider a painter who plans every brushstroke versus one who engages with their medium’s inherent constraints—canvas texture, pigment behavior, light’s ephemerality. The former risks sterile precision; the latter invites discovery. Similarly, literary innovation often thrives under formal duress: James Joyce’s Ulysses reimagined narrative by wrestling with the novel’s limits, while Cubism exploded perspective by adhering to self-imposed geometric rules.

Critically, the sparring partner’s influence is not merely transactional but internalized. Over time, their voice becomes a psychic interlocutor—a “superego” challenging the artist’s instincts. This dialectic transforms constraint into a generative force, as seen in the Flowers in the Dirt sessions: demos and alternate takes reveal not failure but fertile chaos, a process privileging evolution over polished endpoints.

Ultimately, creativity’s highest breakthroughs emerge from such contested spaces—where friction between vision and limitation ignites the unexpected. The sparring partner, as embodied by Costello, proves that constraint isn’t control’s opposite but its antidote: a catalyst for reinvention.

Emergence: Creativity, Constraint, and the Unfolding of the New

Creativity’s most radical leaps often defy intuition: they emerge not from unbounded freedom, but from systems under pressure. Emergence—the phenomenon where complex outcomes arise from simple interactions within constrained environments—reveals a core truth. New ideas, forms, and expressions are born not in voids, but in the friction between limits and experimentation.

This process is neither linear nor predictable. It thrives on dialectical tension—order clashing with chaos, structure with spontaneity. Consider Flowers in the Dirt: the album’s zeniths materialize not from McCartney or Costello’s solo genius, but from the collision of their sensibilities. McCartney’s melodic warmth and Costello’s punk abrasion, when forced into dialogue, sparked a synthesis neither could achieve alone. Here, constraints acted as midwives, delivering something wholly original from the interplay of opposition.

Such dynamics mirror emergence in nature: ant colonies building intricate networks without blueprints, neurons forging thought through synaptic constraints. In art, these “limitations” (formal, relational, or material) are not barriers but generative engines. They compress creative energy until it combusts into the unforeseen.

The Unpredictability of the New

Emergence’s great promise—and peril—is its refusal to be controlled. The novel erupts from constrained systems in ways that elude anticipation, even for those shaping the process. For McCartney, collaborating with Costello meant surrendering to this uncertainty. The result? An album that honored his past while fissuring it open, revealing paths he might never have pursued solo.

This embrace of the unknown is what separates control from constraint. Control seeks to sterilize unpredictability; constraint weaponizes it. A composer writing for a specific instrument (say, the clavichord’s intimate timbre) channels limitation into innovation. Likewise, the raw Flowers in the Dirt demos—unpolished, iterative—capture emergence in motion. Their power lies in exposure: we witness creativity’s messy metamorphosis, untouched by the smoothing hand of overproduction.

To “manage” creativity, then, is not to dictate but to design ecosystems where constraints provoke. It’s the difference between a sculptor chiseling marble (working with the stone’s fractures) and one forcing clay into rigid molds. The former collaborates with limits to uncover latent forms; the latter imposes a brittle vision.

So, what constraints shape your work? Financial limits? Technical boundaries? Collaborative friction? These are not enemies but collaborators. Emergence invites us to reframe them as tectonic plates—grinding against one another until new continents rise. The goal isn’t to escape limits, but to let them sculpt what freedom alone could never imagine.