The American gold and silver that flowed into Spain from the 16th century onward functioned, in effect, as a form of zero-interest money — a steady injection of liquidity into the imperial economy that enabled a dramatic expansion of state power without requiring the structural reforms or productive investments necessary to sustain it. Like the flood of cheap credit in later financial crises, this seemingly limitless resource allowed Spain to finance vast imperial ambitions while masking its underlying economic fragility.

This unearned influx of bullion freed the Spanish Crown from the fiscal discipline required of its rivals. Instead of developing domestic industries, taxing its population effectively, or fostering a productive economy, Spain relied on its colonial extractions to fund wars, maintain its armies, and support a bloated aristocracy. Gold and silver, however, are not inherently productive; they are inert, unable to generate real economic growth unless paired with investment in infrastructure, innovation, or trade. In modern terms, it was akin to a country printing money to pay for its expenses without building the productive capacity to back it.

As with economies dependent on near-zero interest rates, the illusion of wealth fueled a dangerous cycle. Easy money drove inflation — the infamous price revolution of early modern Europe — eroding the purchasing power of Spain’s domestic economy while enriching foreign creditors and merchants. The empire became a net consumer of goods produced elsewhere, particularly in the more industrialized economies of northern Europe. In effect, the bullion Spain extracted at great cost was funneled out of the country almost as quickly as it arrived, enriching its creditors in Genoa, Antwerp, and Amsterdam, while leaving the domestic economy stagnant.

When the bullion flows slowed in the 17th century — much like the end of a low-interest credit boom — the reckoning came swiftly. Without a productive base or diversified economy to fall back on, the Spanish state was left overleveraged and overextended. The empire defaulted repeatedly on its debts, unable to maintain its military commitments or its dominance in Europe. What had seemed like an infinite reservoir of wealth was revealed as a temporary windfall, squandered in pursuit of short-term power rather than long-term stability.

In this sense, the collapse of Spain’s imperial economy offers a clear historical parallel to modern economic crises driven by overreliance on cheap credit. Both highlight the dangers of mistaking access to liquidity for the creation of real wealth and the long-term consequences of failing to use such opportunities to build sustainable economic foundations.

In much the same way that American gold lulled the Spanish Empire into complacency, zero interest rates in the United States over the past few decades have acted as a steady injection of liquidity into the imperial economy. This policy, initiated to stabilize the financial system and stimulate growth, has enabled a dramatic expansion of the American oligarchy, concentrating wealth and power in the hands of a narrow elite. Yet, as with Spain, this influx of easy money has come at the expense of the structural reforms and productive investments necessary to sustain long-term prosperity.

The parallels are striking. Just as Spain financed its wars, debt, and aristocratic extravagance with bullion extracted from the Americas, the United States has sustained its global dominance through the continuous printing of dollars, backed by faith in the financial system rather than tangible economic productivity. Cheap credit has fueled speculative bubbles, enabled vast corporate stock buybacks, and entrenched wealth among the financial elite, while the broader economy remains precariously dependent on consumption, debt, and asset inflation. In both cases, the influx of unearned wealth has fostered a systemic dependence on extraction — of resources, labor, or rents — rather than innovation or production.

Like the Spanish Empire, the United States has neglected the critical work of long-term investment. Infrastructure crumbles, public education stagnates, and industrial capacity has been outsourced in favor of globalized supply chains designed to maximize short-term profits. The trillions of dollars in liquidity injected into the economy through zero-interest rate policies have largely bypassed the real economy, flowing instead into the financial sector. This has enriched a class of oligarchs who now sit atop historically unprecedented concentrations of wealth, but it has failed to build the resilient foundations necessary to sustain a global hegemon.

Meanwhile, just as Spanish gold fueled inflation and destabilized the European economy, America’s low interest rates have created a speculative frenzy in assets, from real estate to tech stocks, driving inequality to extremes and further destabilizing the social contract. The system remains propped up by faith in the dollar, much as Spain’s economy was propped up by the flow of American bullion, but this is a house of cards. When the flow of easy money inevitably slows — as it already has with recent rate hikes — the structural weaknesses will become painfully apparent. Debt burdens will rise, speculative markets will collapse, and the social inequalities papered over by the illusion of liquidity will become impossible to ignore.

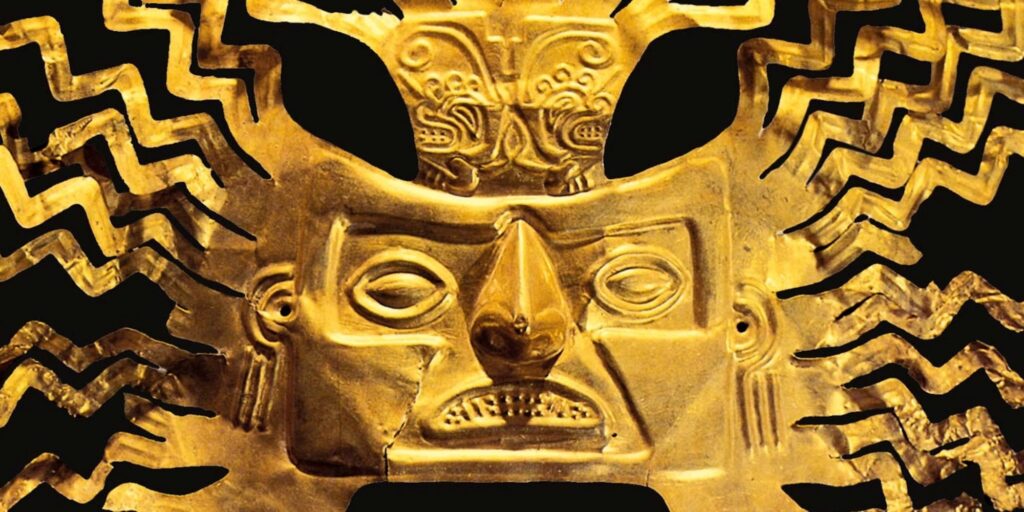

The collapse of Spain’s empire, fueled by its overreliance on Inca gold and silver, was a slow-motion disaster that took centuries to unfold. For 200 years after the bullion flows began to dwindle, Spain clung to its position as a leading nation, still wielding considerable influence in Europe. Yet beneath the surface, the foundations were eroding. By the end of the 19th century, Spain had faded into near-total irrelevance, a marginal power on the global stage.

What’s striking is how long the effects of the bullion-driven economy lingered. The gold and silver that once seemed a limitless source of strength left Spain trapped in a cycle of dependency and stagnation. For nearly 300 years, Spain struggled to transition to a real economy, one based on industry, innovation, and productivity. The legacy of easy wealth shaped its institutions, its social structure, and its politics, long after the flow of precious metals dried up. In some ways, it wasn’t until the late 20th century that Spain fully emerged from the shadow of its imperial past and began to build a modern, diversified economy.

Fast forward to the United States, and the parallels are striking — and unsettling. Like Spain, the United States has relied on an artificial source of wealth: not bullion, but zero interest rate policies and the global dominance of the dollar. This has created an extraordinary concentration of wealth and power in the hands of an entrenched oligarchy. The policies that propped up financial markets have also hollowed out the real economy, fostering inequality and leaving large portions of the population excluded from the supposed benefits of growth.

Yet, as with Spain, the decline of the United States may take much longer than pessimists expect. Empires do not collapse overnight; they erode, their dominance fading gradually even as their elites maintain a façade of control. The sheer scale of America’s economic, military, and cultural power means that the end of its primacy is likely a distant prospect, even if the underlying rot continues to spread.

And there is one crucial difference: while Spain’s aristocracy faded along with its empire, the American oligarchy may prove far more durable. If the lesson of the post-ZIRP era is anything, it’s that the concentration of wealth and power has become self-reinforcing. The systems that sustain the elite are deeply entrenched, and absent significant structural change — which seems unlikely — they are poised to endure.

The long shadow of ZIRP, like the curse of Inca gold, may define this phase of American history. The collapse, if it comes, may still be centuries away, but the conditions for a slow, grinding decline are already in place. And just as Spain took centuries to recover from the legacy of unearned wealth, the United States may one day face its own reckoning. Whether that reckoning takes decades or centuries, one thing seems certain: the oligarchy is here to stay, for the foreseeable future.

The lesson from Spain’s collapse is clear: unearned wealth, whether in the form of gold or artificially cheap capital, cannot sustain an empire. Without structural reforms — investments in productivity, infrastructure, and the real economy — the temporary gains of liquidity-driven growth will eventually lead to decline. The United States, like Spain before it, faces the danger of mistaking the mechanisms of its power for its substance, and the cost of such a mistake will be nothing less than the erosion of its global dominance.