In this analysis of Narcissus and Psyche, we will explore their stories through the lens of cybernetics, systems theory, and distributed consciousness. These frameworks focus on how individuals relate to their environment, the feedback loops they generate, and the mental processes that connect them within larger systems of interaction. Distributed consciousness suggests that different aspects of the psyche are not confined to a single, unified consciousness but are spread across various elements, each influencing the other. Through this perspective, Narcissus and Psyche can be seen as representing distinct, interacting facets of consciousness—self-absorption and relational openness—highlighting the complex dynamics that shape human experience.

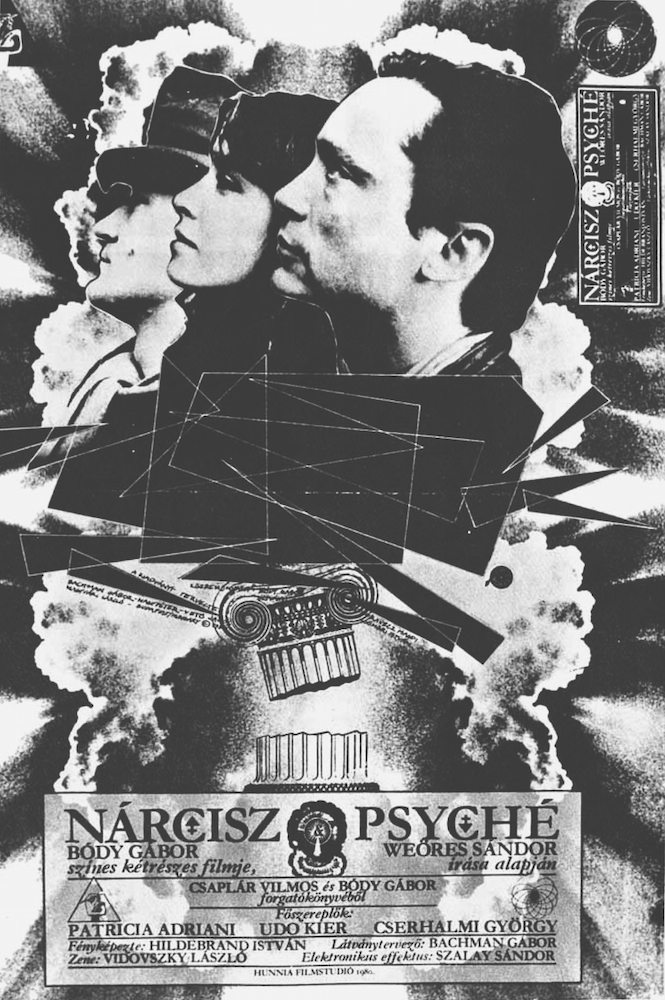

For Gábor Bódy, the sky is not a backdrop but a plane of immanence, a ceaseless becoming, traversed and transformed throughout Narcissus and Psyche (1980). In this sprawling assemblage of period drama and mythic resonance, the figures of Erzsébet (Patricia Adiani) and Laci (Udo Kier)—Hungarian poets caught in the turbulence of the Napoleonic Wars—emerge less as characters than as virtual nodes. Their passions, their agonies, their gestures fold the historical into the mythological, the personal into the cosmic. The film’s title maps Narcissus and Psyche not as fixed identities but as refrains, expressive modulations of the eternal return of gendered becoming: woman as metamorphosis, artist as self-fracture. “I believe in neither the Roman nor the Helvetian God,” declares Laci, “only in the aesthetic and historic authority of the Greek-Latin gods.” Yet this appeal to an archaic authority is deterritorialized by Bódy’s camera, which captures clouds not as symbols but as pure flux: an infinite series of patterns, intensities, and movements, defying any fixed organization of the heavens.

Against the sedimented codes of his contemporaries—the slow, mordant gestures that would come to define Hungarian cinema—Bódy sets loose a machine of dizzying velocities, which J. Hoberman aptly describes as “products from an alternate dimension.” His earlier American Torso (1975) similarly refuses linearity, folding the Hungarian Revolution of 1848 into the Civil War through a cinema of temporal fissures. Here, the “light editing” method—scratches, exposures, disruptions—decomposes the filmic surface, producing not a narrative of history but a delirial archaeology of time, a flickering palimpsest that erases itself even as it inscribes.

In Narcissus and Psyche, Bódy radicalizes this process. Across its four-hour duration, the film oscillates between Napoleonic set-pieces and kaleidoscopic disruptions, each scene an assemblage of contradictory forces. Scrupulous blocking dissolves into anarchic editing, compositional coherence into machinic frenzy. This is not a cinema of equilibrium but of tremor, vibration, and excess. Bódy’s insistence on perpetual movement—on the trembling of every frame—anticipates his embrace of cybernetics and video, which he celebrated for their capacity to “represent chance.” His cinema does not narrate but diagrams, organizing chaos into the poetry of contingency. It is a cinema of the virtual, a praxis of the future, where history liquefies into an aleatory field of possibility.

• Narcissus would represent the dangers of a closed feedback loop that becomes isolating and self-destructive. In Bateson’s terms, Narcissus’ relationship to his reflection lacks any external validation or “other” to break the cycle. The mirror image feeds back only what Narcissus projects, creating a self-reinforcing loop that ultimately leads to his downfall. Bateson would interpret Narcissus’ fixation as an example of how a system that closes off from meaningful feedback eventually leads to entropy and collapse. Without an open system to allow for dynamic interaction and learning, Narcissus is trapped within a self-referential echo, illustrating the notion that mental systems require diversity and exchange to sustain themselves. Narcissus is essentially caught in a “schismogenic” process—one where the repeated interactions (his gaze) escalate into a pathological fixation.

• For Psyche, we could focus on her journey as an adaptive learning process within a dynamic system. Psyche’s relationship with Cupid is initially shrouded in mystery, and her trials represent different forms of learning and adaptation. Each task Psyche faces is a feedback mechanism that teaches her about herself, her limitations, and her desires. We see these tasks as a form of double bind, where she must navigate contradictory instructions or impossible choices (e.g., loving Cupid without seeing him). Her perseverance through these binds reflects an evolution of mind in the Batesonian sense—she moves through different stages of learning and understanding her environment, shifting from dependence on rules imposed by the gods to an internalized wisdom about love, trust, and resilience. Psyche’s journey thus represents an open system where feedback (each task) is assimilated, transformed, and adapted to produce growth.

In this sense, Narcissus warns against systems that close off from external interaction, becoming stagnant and self-destructive. Psyche, in contrast, illustrates a self-regulating system that adapts to new information, learning from challenges and maintaining openness to external forces (represented by the gods and Cupid). We can interpret her journey as a positive feedback loop—each task reinforces her capacity to adapt, grow, and learn, allowing her ultimately to transcend her previous state and reach a more integrated form of being.

In summary, using this interpretation would see Narcissus as an example of a rigid system failing due to self-isolation, while Psyche embodies the flexible, adaptive system that thrives by interacting dynamically with its environment, using feedback to achieve a more evolved state of consciousness.

Psyche’s punishment

Psyche’s story includes significant trials imposed by Aphrodite (or Venus in the Roman version). Aphrodite’s jealousy of Psyche’s beauty and her love for Eros (Cupid) sets up the sequence of punishments Psyche must endure. Each trial Aphrodite demands is designed to be impossible, reinforcing Psyche’s subservient and “inferior” status, and they are intended to keep Psyche from reaching her beloved.

We could understand this dynamic as part of a system of power and control where Aphrodite represents an entrenched authority figure attempting to impose limits on Psyche. Aphrodite’s attempts to control Psyche are an example of hierarchical structure in a system, with rigid boundaries where older powers seek to enforce their dominance over emerging ones.

From this perspective:

1. Aphrodite’s Punishments as Control Mechanisms: Bateson might view each task given by Aphrodite as a form of control intended to enforce conformity and maintain the established hierarchy. Each trial Psyche undergoes can be seen as a way of testing and reinforcing her “place” within the system. This dynamic mirrors cybernetic feedback loops where systems can become either adaptable or self-reinforcing. Aphrodite, as a representative of a “closed” system, seeks to keep the old structure intact and prevent new connections (such as the union of Psyche and Eros) from disrupting her status.

2. Psyche’s Adaptive Responses: In overcoming each trial, Psyche demonstrates second-order learning, where she evolves by interpreting her challenges differently rather than simply repeating old patterns. Each task she completes reflects her ability to adapt to a seemingly rigid system. For example, when faced with impossible tasks like sorting seeds, gathering golden fleece, or descending into the underworld, Psyche accepts help from external sources (ants, a reed, or divine interventions). This openness to assistance and flexibility mirrors The ideal of an open, learning-oriented system that incorporates external input, adapts, and grows rather than becoming fixed or rigid.

3. Reconfiguration of the System: Psyche’s final transformation into an immortal being, allowed by Zeus, can be seen as a reconfiguration of the hierarchical system. In the end, the “closed” system symbolized by Aphrodite’s dominance is partially dissolved to accommodate a new structure where Psyche, initially a mortal outsider, becomes integrated as an immortal, equal partner with Eros. Bateson would likely interpret this as a system that has evolved to maintain balance by incorporating new elements, adapting in a way that sustains the whole.

Narcissus and Psyche

In this terms, Psyche could be seen as the literal “psyche” of Narcissus—the adaptive, relational potential within him that he never realizes. Narcissus and Psyche are like two parts of a system: Narcissus represents the rigid, self-referential part that refuses to change, while Psyche embodies the open, flexible part that learns and evolves through experience.

If Narcissus and Psyche were viewed as two aspects of a single mind, Narcissus would be the isolated loop, endlessly feeding back on itself without external input or growth. Psyche, however, would be the part of the mind that engages with the world, adapts, and draws on new information to create meaning beyond itself.

Thus, in this framework, Psyche is what Narcissus’s psyche could be if it escaped its own self-imposed isolation. Psyche’s journey represents a mind that can learn, adjust, and expand—traits Narcissus lacks as he remains trapped in his closed system. If he could integrate Psyche’s openness, Narcissus might escape his self-absorption and connect with a broader, more balanced existence.

Greek Myths and Distributed Conciousness

Greek myths can indeed be understood as an example of distributed consciousness. Rather than having a single, unified perspective or consciousness, Greek mythology presents a universe where different aspects of human experience, emotion, and thought are distributed across a pantheon of gods, demigods, and mortals, each embodying distinct traits and drives.

In this sense, characters like Narcissus and Psyche can be viewed as parts of a larger, distributed psyche—each representing a unique aspect of human consciousness and inner conflict. Narcissus embodies self-reflection taken to the extreme, a form of consciousness that becomes so self-focused it loses touch with others and reality itself. Psyche, on the other hand, symbolizes a consciousness that learns through challenges, gradually developing resilience, adaptability, and connection. Together, they reflect a balance of forces: self-absorption versus relational openness, rigidity versus transformation.

In Greek myths, this distribution of consciousness means that no single character encapsulates the entire human experience. Instead, each god, hero, and mortal personifies a different facet—love, jealousy, wisdom, vanity, courage, etc.—interacting in ways that mirror the internal tensions and synergies within a single mind. When these characters clash, ally, or transform, they create a narrative representation of an inner world where different impulses and perspectives continuously negotiate with one another.

This distributed consciousness also reflects a worldview where human identity is not isolated but embedded in a broader web of relationships, emotions, and archetypal forces. Myths like those of Narcissus and Psyche can thus be seen as metaphors for the complex interplay within an individual’s psyche, showing how different “selves” or drives interact, conflict, or harmonize to shape our experience and behavior. Through this lens, Greek mythology captures the fragmented, multifaceted nature of consciousness itself, showing how meaning and identity arise from an intricate network rather than a single source.