Akira Kurosawa’s Style: An Unforgettable Blend of Visual Mastery and Musical Brilliance

Introduction: Akira Kurosawa, the legendary Japanese filmmaker, is renowned for his exceptional style and artistic vision. His filmmaking techniques and creative choices have left an indelible mark on the world of cinema. From his innovative use of long zoom lenses to his meticulous scene blocking, Kurosawa’s approach to visual storytelling continues to captivate audiences. Additionally, his collaboration with composer Masaru Sato, who skillfully blended classical, Japanese traditional, Ainu folk music, as well as Western and light jazz influences, further enriched his films. This essay delves into the remarkable characteristics of Kurosawa’s style, emphasizing the significance of packed frames, the mastery of scene blocking, and the musical genius that accompanied his visual narratives. Moreover, it explores the parallels between the use of ideograms and film montage, drawing connections between the concise nature of haiku and the economy of storytelling in Kurosawa’s films.

Packed Frames and Scene Blocking: One of the distinguishing features of Kurosawa’s visual style is the incredible density of his frames. With his adept use of long zoom lenses, typically ranging from 35mm to 50mm, Kurosawa carefully constructed scenes that were teeming with details. Every corner of the frame contained purpose and significance, enhancing the depth and richness of his storytelling. Whether it was the bustling chaos of a battle sequence or the nuanced interactions between characters, Kurosawa masterfully utilized every inch of the frame to convey his narrative. This meticulous attention to detail created a sense of immersion, pulling the audience into a world that felt vibrant, dynamic, and lived-in.

In addition to packed frames, Kurosawa’s scene blocking exhibited a balletic quality that remains awe-inspiring to this day. His ability to choreograph the movements of actors within the frame showcased his profound understanding of visual storytelling. Each character’s positioning and movement were carefully orchestrated to communicate emotions, relationships, and power dynamics. Whether it was a samurai duel or a simple conversation, Kurosawa’s blocking transformed his films into beautifully orchestrated performances. The balletic nature of his scenes elevated the impact of his narratives, fostering a sense of harmony and fluidity that made his films a joy to watch.

Musical Brilliance and Influence: Masaru Sato’s musical compositions played a pivotal role in complementing and enhancing Kurosawa’s visual storytelling. Sato’s genius lay in his ability to blend various musical styles, including classical, Japanese traditional, Ainu folk music, as well as Western and light jazz influences. This eclectic fusion not only added depth and cultural richness to Kurosawa’s films but also set a precedent for future composers like Ennio Morricone.

Sato’s scores created a seamless harmony between sound and image, amplifying the emotional impact of Kurosawa’s scenes. Whether it was the grandeur of an epic battle or the quiet introspection of a character, Sato’s music heightened the audience’s connection to the story unfolding on screen. The blend of classical elements, Japanese traditions, and diverse musical influences mirrored Kurosawa’s own stylistic approach, which seamlessly merged cultural and artistic influences from both East and West.

Ideograms and Film Montage: Kurosawa’s affinity for concise storytelling finds an intriguing parallel in the world of ideograms, particularly in the form of haiku. Both mediums employ the art of economy, distilling complex emotions and narratives into succinct and evocative forms. Just as a haiku captures the essence of a moment or sentiment in three lines, Kurosawa utilized film montage to convey meaning through concise visual juxtapositions.

Akira Kurosawa’s frame composition exhibits a striking resemblance to the concise and evocative nature of ideograms. Ideograms, such as Chinese characters or Japanese kanji, convey meaning through visual representation rather than phonetic sounds. Similarly, Kurosawa’s use of visual elements within the frame communicates information, emotions, and symbolism with remarkable efficiency.

In Kurosawa’s films, each frame is meticulously composed to capture the essence of a scene or a character’s state of mind. Just as an ideogram distills complex concepts into a single character, Kurosawa condenses layers of meaning into his frame compositions. Every object, every actor’s position, and every visual element within the frame contributes to the overall message and narrative.

Kurosawa often employed symbolism in his compositions, using visual metaphors to convey deeper themes and ideas. These symbolic elements, akin to the strokes and components of an ideogram, combine to form a cohesive and resonant visual language. For example, in “Rashomon,” the iconic sequence of sunlight streaming through leaves reflects the fragmented nature of truth and the subjective perspectives of the characters.

Furthermore, Kurosawa’s use of space within the frame is reminiscent of the negative space found in ideograms. Negative space, or the empty areas surrounding the main subject, is as important as the subject itself in conveying meaning. Similarly, Kurosawa’s deliberate use of empty spaces in his compositions creates a sense of tension, anticipation, or contemplation. The balance between filled and empty spaces, much like the balance of strokes and white spaces in an ideogram, adds visual harmony and emphasizes the intended message.

Additionally, Kurosawa’s incorporation of movement within his compositions shares similarities with the dynamic nature of stroke order in writing ideograms. The sequence and direction of strokes in an ideogram are carefully structured to create a sense of flow and rhythm. Similarly, Kurosawa’s blocking of actors and their movements within the frame creates a visually choreographed dance, where the flow of bodies and actions enhances the narrative’s impact. This dynamic composition reflects the inherent movement and energy found in ideograms.

Moreover, Kurosawa’s penchant for visual contrasts and juxtapositions aligns with the concept of ideograms representing opposing or complementary elements. Ideograms often combine distinct visual components to create meaning, such as fire and water forming the character for “steam.” Similarly, Kurosawa skillfully employs contrasting visual elements within his frames, such as light and darkness, or static and dynamic elements, to create visual tension and thematic depth. These visual dichotomies, like the combination of strokes in an ideogram, form a cohesive whole that conveys complex ideas concisely.

In summary, Kurosawa’s frame compositions bear resemblance to the concise and symbolic nature of ideograms. Through careful visual arrangements, use of space, incorporation of movement, and dynamic contrasts, he condenses layers of meaning into each frame. In this way, Kurosawa’s films become a visual language that communicates profound ideas and emotions with the economy and resonance akin to the power of ideograms.

Here are ten examples of ideograms and corresponding scenes from Akira Kurosawa’s films:

- Ideogram: Water (水) Scene: The rain-soaked battle scene in “Seven Samurai,” where the muddy terrain and waterlogged samurai emphasize the challenging conditions faced by the warriors.

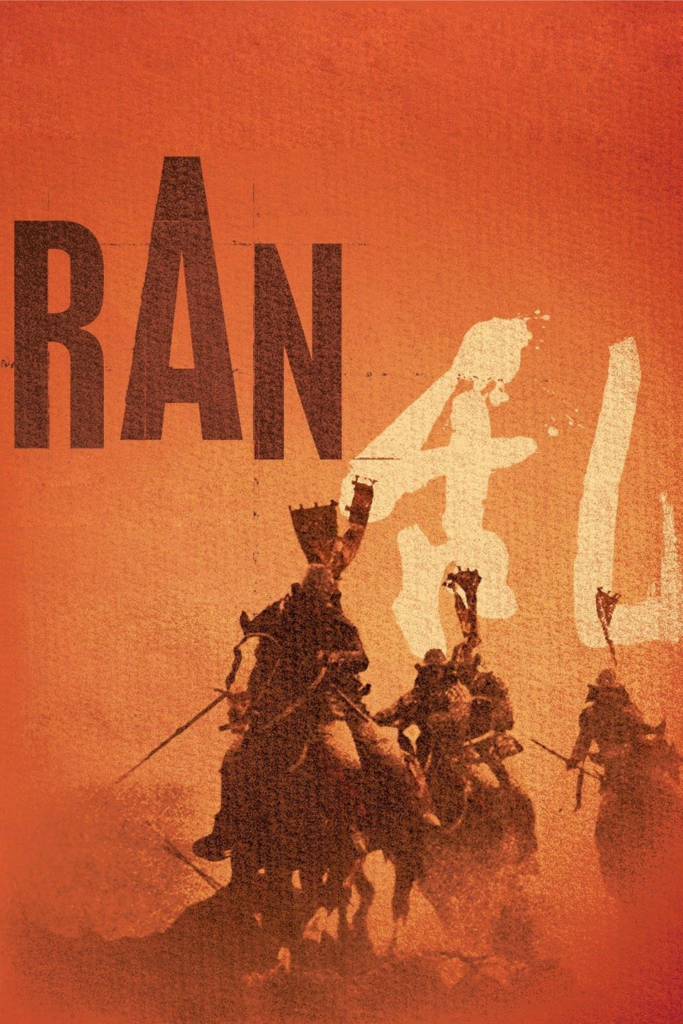

- Ideogram: Sun (日) Scene: The iconic shot of sunlight piercing through the clouds in “Ran,” symbolizing the fleeting moments of hope and illumination amidst chaos and darkness.

- Ideogram: Tree (木) Scene: The scene in “Rashomon” where the bandit’s confession takes place under a massive tree, representing nature as a silent observer of human deeds and morality.

- Ideogram: Fire (火) Scene: The burning castle sequence in “Throne of Blood,” showcasing the destructive power of ambition and betrayal as the flames consume the fortress.

- Ideogram: Mountain (山) Scene: The panoramic shots of majestic mountains in “Dersu Uzala,” depicting the awe-inspiring beauty of nature and the spiritual connection between humans and the natural world.

- Ideogram: Heart (心) Scene: The close-up of the protagonist’s face in “Ikiru,” capturing his profound inner struggle and transformation as he contemplates the meaning of life.

- Ideogram: Sword (刀) Scene: The climactic duel in “Yojimbo,” where the protagonist’s swordplay embodies the conflict between honor and self-interest in a lawless world.

- Ideogram: Bridge (橋) Scene: The bridge battle scene in “The Hidden Fortress,” featuring the intense struggle between samurai and bandits as they fight for control of the passageway.

- Ideogram: Flower (花) Scene: The blossoming cherry trees in “Dreams,” symbolizing the ephemeral beauty of life and the fleeting moments of joy and serenity.

- Ideogram: Moon (月) Scene: The moonlit night scene in “Sanjuro,” with the moon serving as a silent witness to the unfolding intrigue and the hidden intentions of the characters.

These examples highlight how Kurosawa expertly incorporates visual elements and symbolic imagery to convey deeper meanings and evoke emotions within his scenes, akin to the concise and evocative nature of ideograms.