In the world of music, there is a common expression used to describe something that is easy to achieve or attain, but may lack depth or originality: “low-hanging fruit”. In the context of rock music, the concept of “low-hanging fruit” can refer to the use of common musical cliches or overused chord progressions that are easy to play but may limit the potential for creativity and self-expression. In this essay, we will explore how the reification of “low-hanging fruit” in rock music can create barriers to self-expression in the genre’s vocabulary.

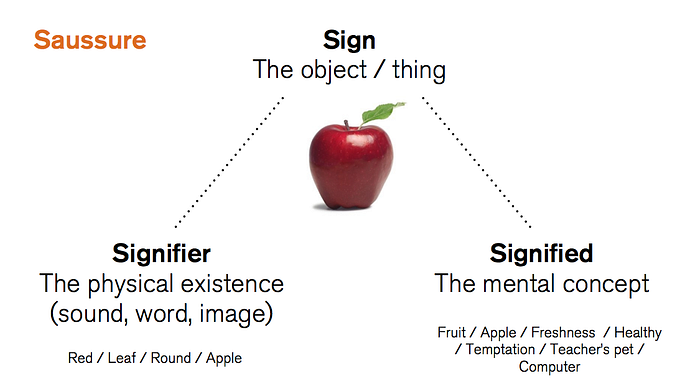

Reification is the process of transforming an abstract concept into something concrete or tangible. In the context of rock music, reification can refer to the transformation of an artistic expression into a product that can be marketed and sold. The use of “low-hanging fruit” in rock music can contribute to this process, as it can lead to the homogenization of the genre, where all the music sounds the same and lacks individuality and creativity.

The use of common musical cliches and overused chord progressions in rock music can be traced back to the emergence of the genre in the 1950s and 1960s. Many of the early rock and roll songs followed a simple 12-bar blues progression, which was easy to play and became a standard in the genre. As rock music evolved, other chord progressions became popular, such as the I-IV-V progression or the relative minor progression. These progressions were easy to learn and play, and many bands started using them as a formula for their songs.

However, the overuse of these progressions and other musical cliches can limit the potential for creativity and self-expression in rock music. When a musical vocabulary becomes standardized, it can create barriers for artists to express their unique ideas and emotions. Instead of exploring new sounds, ideas, and approaches, artists may feel pressured to follow the established norms and conventions of the genre, which can stifle their creativity and originality.

This create barriers to self-expression in the genre’s vocabulary. The overuse of common musical cliches and overused chord progressions can limit the potential for creativity and originality, and contribute to the homogenization of the genre.

Music has become a powerful tool in promoting consumerism. Songs and music videos often feature brands and products, with artists being used as spokespersons for commercial products. Many musicians have been co-opted into promoting consumerist lifestyles, with their images and music being used to sell products and services to consumers. This has led to the reification of consumerist behaviors, where material possessions and lifestyle choices are elevated to the status of cultural values.

The exaptation of music has had both positive and negative effects on the industry. On the one hand, it has enabled artists to reach a wider audience and monetize their music in new and innovative ways. On the other hand, it has led to concerns about the impact of commercialization on the artistic integrity of music and the ability of artists to express themselves freely without being constrained by commercial considerations.

No matter where you stand on this, it’s obvious that all facets Rock’n’Roll, be it prog, Metal, blues, indie etc faces a mounting artistic problem: that almost everything about it is a foregone conclusion: from the intro riffs to the choruses all the way down to the lyrics. Getting new is harder.

There are riffs and there are bridges and there are choruses And this wouldn’t be so bad if was in service of a larger musical idea. But no. But all we get is well worn references linked together with forgettable filler. A big budget greatest hits medley.

THE BLACK KEYS

So, let’s talk about the Black Keys and how their music borrow from other composers and bands. I should say at the outset, that I own all Black keys album and have enjoyed their music, and I should also say it’s impossible for a piece of music to avoid doing this. Dan Auberbach and Patrick Carney don’t really begin each new work with a completely ‘blank canvas’ because they carry with them what the philosopher Theodor Adorno calls ‘the handed-down musical materials of history’ — which are the genres, tonalities, structures and other musical traditions that we all grow up with.

Things that already have meanings, rules and associations tied to them. So music is always reified to a certain degree. While writing the music for their albums, The Black keys or QOTSA or the Foo Fighters draw from a large range of well known sources. There’s heavy referencing of Led Zeppelin, Canned Heat, Jim Kimborough, Bachman Turner Overdrive etc. While Patrick Carney grew up on punk groups like The Clash and the Cramps, Dan Auerbach came up on bluesmen like Junior Kimbrough and southern rockers like Lynyrd Skynyrd. Throw in Steppenwolf, T. Rex, and Captain Beefheart/.

“Little Black Submarines” is very similar to “Stairway to Heaven” by Led Zeppelin but I’m not saying that Black Keys or QOTSA are plagiarists or hacks because the artistry in their music is in combining musical ideas with pre-existing meanings to form new meaning, breathing life into the original genres and conjuring a sense of otherworldliness and fantastical adventure. Like all music, there is a certain degree of reification going on, but it’s very creative.

So the problem then is one of degrees. In other words, there comes a point where a piece of music is so reified that it’s glued up completely; where its meaning is so obvious that there’s no room for maneuver. This can be illustrated by looking at the newer albums QUOTSA, FOO FIGHTERS — which for me sit here on the reification-o-metre (- pretty reified.- very reified).

This time, they are working without Danger Mouse, the producer whose modern/retro fusion helped prime the band for their crossover. His fingerprints in particular were all over the psychedelic hodgepodge of Turn Blue and its kitchen-sink strings and keyboards. “Let’s Rock,” in turn, opts for a streamlined approach: just Auerbach, Carney, a pair of backing vocalists and as many overdubs as it takes to get the job done.

In truth, Danger Mouse’s absence leaves more room for riffs, and “Let’s Rock” doesn’t skimp on them. “Shine a Little Light” kicks off with a torrent of brawling guitars, the embodiment of those old speaker ads with the guy in a chair blowing away his living room. “Lo/Hi,” about reckless thrills and brutal comedowns, is even more undeniable, pure leather-jacketed swagger.

Most of “Let’s Rock” hits its mark, but sometimes the band cribs so overtly from their influences that it feels like cheating off of a test. The guitars on “Walk Across the Water” ape the suave glide of T. Rex’s “Jeepster,” while “Sit Around and Miss You” lifts its lick so shamelessly from Stealers Wheel’s “Stuck in the Middle With You” that it’s hard to hear it without picturing Michael Madsen slicing off a dude’s ear.

Elsewhere the influences are subtler — shades of Steely Dan in the amplified soft-rock of “Breaking Down,” a hint of the Isley Brothers in the nimble lick of “Tell Me Lies.” The Black Keys are no longer really drawing from different musical inspirations to create new experiences. They are largely drawing from himself to create the same experience.

Since so many big moments rely on pre-existing material. And the problem with reusing pre-existing material is one of diminishing returns. At its worst, rehashed music can descend into meaninglessness. To give an example of what I mean, let’s look at the use of Wagners ‘Ride of the Valkeries’ in film.

When used in Apocalypse now it was a deliberate artistic juxtaposition — drawing from the original meaning of the music to provide a subtext of false glory and horror. It was done to make us think. Now let’s look at it’s reuse in the film ‘Watchmen’ directed by Zack Snyder.

The music here isn’t appropriate at all because the intention of this part of the story, written by the fantastic Alan Moore, was to illustrate the complicated inner struggles and regrets of one of the main characters. But Snyder, as always, employs the lowest common denominator approach: ‘since Apocalypse Now takes place in Vietnam and this scene takes place in Vietnam let’s just use the Apocalypse Now music.

The music is now super-reified. Ride of the Valkyries isn’t being used for any deeper meaning — it just means ‘Vietnam — but also, remember Apocalypse Now?’.

And it’s this meaninglessness that Rock’n’Roll is in danger of going towards if mishandled. lifted the well worn themes we’ve heard a million times and placed them at strategic moments to achieve maximum cliche.

GUITARS

During and immediately after World War II, with shortages of fuel and limitations on audiences large jazz bands tended to be replaced by smaller combos, using guitars, bass and drums. In the same period, particularly on the West Coast and in the Midwest, the development of jump blues, with its guitar riffs, prominent beats and shouted lyrics, prefigured many later developments. Keith Richards proposes that Chuck Berry developed his brand of rock and roll by transposing the familiar two-note lead line of jump blues piano directly to the electric guitar, creating what is instantly recognizable as rock guitar. Similarly, country boogie and Chicago electric blues supplied many of the elements that would be seen as characteristic of rock and roll.

So now, what’s possibly the most reflective and powerful weapon in Rock’n’Roll is just being thrown around to give weight to a moment that would otherwise feel pretty silly. This I think gets to the route of the problem. The original use of guitars had enormous power because of how it was structured. Inspired by electric blues, Chuck Berry introduced an aggressive guitar sound to rock and roll, and established the electric guitar as its centrepiece, adapting his rock band instrumentation from the basic blues band instrumentation of a lead guitar, second chord instrument, bass and drums.

65 years later and there is never a moment when I felt it was being used as a storytelling device as much as a dog whistle. It doesn’t provide any kind of deeper meaning or allow me to ponder or interpret way was going on. Its sole function was to point out when something rock related was happening, which I already knew about because I’m listening to the album. This is extreme reification and it hurts the movie. Perhaps it’s time to consider organizing rock’n’ roll in a different way. It doesn’t have to be based on guitars.Or it could be different guitars. Think King Gizzard and the Lizzard Wizard microtonal guitars.

This music was new to us and we now associate it with youthful folly and their plight. Later on, when it branches out into different styles like progressive rock etc it emerges more powerfully. It’s now tragic because the Boomer’s wish has been granted in the most horrible possible way. Then, at the climax of the genre, the theme reappears one more time to mark the moment that boomers overcome their self-doubt, thereby completing their character arc in a meaningful and satisfying way.

The style develops as the boomers develops. This is how you tell a story with music. Now look again at the Black keys. Oh look… it’s that guy… from the commercial … except the music is now telling you what to feel. It isn’t earned. It’s cashing in that cheque written by the original generation. But it’s not a blank cheque. Eventually, this theme will lose its potency completely, it will become a known artefact that disallows interpretation.

So part of the problem here is audience expectation. I’m going to call this the ‘I know what that is’ conundrum. Because we’re all familiar with the Rock’n’Roll musical language. ….. Composers are faced with the choice of either referencing that language or abandoning it to create new music. With the latter, composers open themselves up to criticism by not doing what people expect and run the risk of their creative experiments failing.

By quoting established material, they’re guaranteed some degree of acceptance while avoiding the possibility of misinterpretation. Audiences are often very insistent on seeing and hearing things that they recognise and the compulsion to give into this demand is very powerful

Being different is dangerous but it’s also the only way to achieve new heights. This leads me to a quick aside about Rock’n’Roll as a consumer product: many post-marxist thinkers use the concept of reification to attack aspects of modern capitalism. One famous argument, again from the philosopher Theodor Adorno is that art in capitalist societies have a tendency towards intellectual stagnation due to the financial interests involved — because complicated and thought-provoking art is less likely to appeal to mass audiences it will therefore will not satisfy one of the hallmarks of capitalism, which of course is mass production motivated by profit.

Now, it’s not hard to see how the Rock’n’Roll collapsing industry can be used as an example to back up this argument — with what remains of the music industry being too afraid to deviate from customer expectation and choosing bands who are happy to churn out very similar material over and over again. It’s up to you to decide to what extent this is happening but it seems to me pretty obvious that it is, at least, happening.

MUSIC B

NOTHING MUSIC

So one of the unfortunate consequences of businesses appropriating this kind of music for advertising is that corporate hacks get so used to it. It’s not long before it begins to affect how they communicate through music with their customers.

The purpose of using music is to help sell the idea that product being sold is the culmination of some kind of profound altruistic endeavor aimed at the betterment of humanity. And when they’re not going the ‘we’re making the world a better place’ route… then … sigh… they instead go for the ‘isn’t life just awesome!’ route.

Then there is we’ve designed a ludicrously expensive gadget to help — until it breaks or until we design something even more expensive. Let’s make the world a brighter place by wasting our disposable income!

For this you’ll need monorhythmic piano chords. Every year the destruction of the Amazon Rain Forest intensifies. This makes us sad. Here at Shell, we are sad. And that’s what Music that stands for Late Stage Capitalism is. Pretending. Pretending to be something a human would write

And no matter how hard it tries, it just can’t help but reflect the banality and inauthenticity of the corporation that uses it. And that, I suppose, is the one emotional insight it’s capable of providing… it is a pretty accurate portrayal of what corporate life is really like: dull, hackneyed and completely lacking in substance.

TCHAIKOVSKY

Tchaikovsky was working on the first movement of his 4th symphony in 1877. However, he was faced with a problem: at that time, the first movement of a symphony was always structured according to something called ‘sonata form’ — a detailed process where two very small musical ideas are weaved together to form a large musical journey.

This is a very analytical and abstract way of writing — where the goal is sense of musical ‘resolution’ at the end. However, this formula didn’t sit well with some Romantic composers at the time because it resisted their more modern interest in storytelling and biographical self-expression.

In this case, Tchaikovsky was in the middle of a personal crisis: he had recently married — a move generally considered to have been a smokescreen to hide his homosexuality from the public — and it had ended in acrimonious disaster after only a couple of months, leaving him with feelings of depression and alienation. So going into his 4th symphony, it was these emotions that he wanted to express.

But the highly technical framework of the sonata form was a problem: feelings relating to an identity crisis are difficult to express when following a tried and tested formula. However, due to audience expectation, Tchaikovsky didn’t feel that he could simply discard sonata form altogether and so decided to make some now very famous alteration— the insertion of an unexpected waltz in the first movement.

By today’s standards that sounds almost laughably unrevolutionary but consider the social function of the waltz at that time: found at events where young men and women of the elite would dance, form connections and generally have a good time. Tchaikovsky’s use of the waltz — shoved into a structure it was never intended for — Mirrored his own feelings of social failure — an inability to dance in step with everyone else.

The emotional quality of the music was also unique — for all the attempts of the Waltz to sound light-hearted and frivolous, it was being knocked about by dark and turbulent symphonic forces — a hopeless display of frivolity that reflected the futile charade of his own marriage. In other words, Tchaikovsky took structural expectation and used it as a way to communicate something completely unique about his own experience.

SET IT FREE

So, in short, Rock’n’Roll needs to change. We should not as audiences expect to be pandered to by relentless reference to stuff we know. It will never satisfy us. The original tunes were, well, original and that’s the only thing — originality — that has any hope of delivering a truly breathtaking new Rock’n’Roll experience. And if that entails throwing away what we know so what? It’s a price worth paying. Familiarity and recognition are nice but they can never replace the feeling of a completely novel experience.

If you love it, set it free