Keith Johnstone’s theories on spontaneity, storytelling, status, and mask work are well-known in the world of theater and improvisation. His ideas on improvisation go beyond simply teaching actors how to think on their feet; they explore the deeper psychological and neurological mechanisms that underlie creativity and performance. In this essay, we will explore Johnstone’s theories through the lens of neuroscience and psychology, and see how they fit into our current understanding of the mind and consciousness.

One of the key ideas behind Johnstone’s theories is the concept of spontaneity. According to Johnstone, spontaneity is the ability to act without conscious thought, to simply allow oneself to be carried by the flow of the moment. This is a concept that is well-understood in neuroscience and psychology, where it is often referred to as “flow” or “the zone.” In this state, the prefrontal cortex, which is responsible for conscious thought and decision-making, is quieted, allowing other areas of the brain to take over. This can lead to a sense of effortless action and a feeling of being “in the zone.”

Masks signaling spontaneity:

- Anonymous masks used by members of the hacktivist group Anonymous to conceal their identities while engaging in online activism and spontaneous protests.

- Masks used by street performers such as mimes and buskers to draw attention and create a spontaneous atmosphere in public spaces.

- Masquerade masks used in parties and events where participants are encouraged to act spontaneously and engage in social interaction without revealing their true identity.

Another important concept in Johnstone’s theories is storytelling. Johnstone emphasizes the importance of creating compelling narratives in performance, and he encourages actors to tap into the power of archetypes and mythological themes. From a psychological perspective, this is an important aspect of human cognition. We are wired to understand the world through stories, and our brains are constantly looking for patterns and narratives in the world around us. By tapping into these innate cognitive processes, actors can create performances that resonate deeply with audiences.

Masks signaling storytelling:

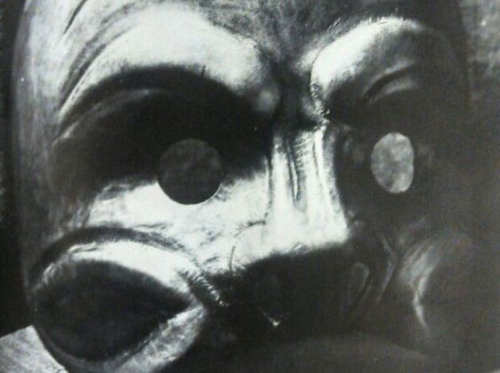

- Masks used in traditional theatre performances such as Noh and Commedia dell’arte to represent specific characters and emotions in a story.

- Masks used in storytelling traditions such as Native American and African tribal cultures to represent characters and spirits in folktales and myths.

- Masks used in contemporary theatre productions to represent metaphorical or symbolic concepts such as death, love, or fear.

Status is another important concept in Johnstone’s theories. He argues that status is not simply a matter of social hierarchy; it is a fluid and dynamic phenomenon that is constantly shifting in response to social cues and context. From a neuroscience perspective, this makes sense. Our brains are wired to be acutely sensitive to social cues and status hierarchies, and we are constantly processing this information on a subconscious level. By understanding the nuances of status and social dynamics, actors can create more believable and nuanced performances.

Masks signaling status:

- Masks used in ceremonial or religious contexts to represent higher beings or deities, such as the masks used in the African masquerade tradition.

- Masks worn by high-ranking officials and dignitaries during formal events or ceremonies to signify their status and authority.

- Masks used in traditional cultures to represent social status or caste, such as the mask traditions in Bali, Indonesia, where masks are used to represent royalty or warriors.

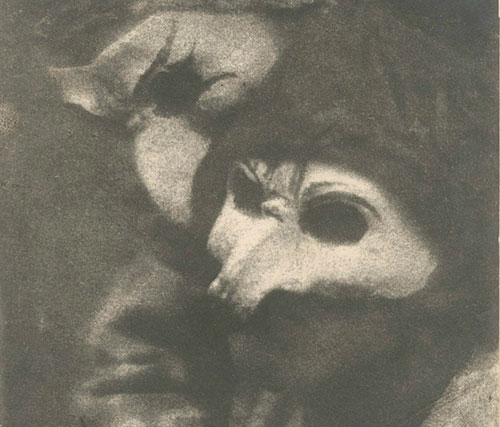

Perhaps the most fascinating aspect of Johnstone’s theories is his work on mask work. Johnstone argues that masks can create altered states of consciousness and even induce trance states or amnesia. From a neuroscience perspective, this is a complex phenomenon that is still not fully understood. However, we do know that our consciousness is not solely located in the brain. Our bodies and our environments play a crucial role in shaping our subjective experiences, and our sense of self is deeply intertwined with our physical and social contexts. By using masks to alter these contexts, actors can create performances that transcend the boundaries of normal conscious experience.

THEORY OF MIND

Johnstone’s theories on improvisation and performance rely on a situated cognition and embodied theory of the mind. This approach emphasizes the importance of our bodies and environments in shaping our subjective experiences, rather than viewing consciousness as solely located in the brain.

Situated cognition is a theory that posits that knowing is inseparable from doing by arguing that all knowledge is situated in activity bound to social, cultural and physical contexts.

Situated cognition is a perspective that argues that cognitive processes are not solely determined by internal mental representations, but are also influenced by the context in which they occur. This means that our cognitive processes are situated in our physical and social environments, and that our environment plays an active role in shaping our subjective experiences. Johnstone’s theories on improvisation and performance are consistent with this perspective, as they emphasize the importance of the actor’s physical and social context in shaping their performances.

Embodied cognition is another perspective that emphasizes the importance of the body in shaping our cognitive processes. This approach argues that cognition is not just a matter of mental representations and computations, but is also grounded in the body and its interactions with the environment. Johnstone’s theories on mask work are consistent with this perspective, as he argues that masks can create altered states of consciousness and induce trance states or amnesia. By altering the actor’s physical and social context, masks can fundamentally change the way they experience and interact with the world.

NOTES

Notes: Keith Johnstone, “Masks and Trance.” (Impro, Theater Arts Books, Routledge, 1992)

“It’s true that an actor can wear a Mask casually, and just pretend to be another person, but as Gaskill and myself were absolutely clear that we were trying to induce trance states. The reason why one automatically talks and writes of Masks with a capital ‘M’ is that one really feels the genuine Masked actor is inhabited by a spirit. Nonsense perhaps, but that’s what the experience is like, and has always been like. To understand Mask it’s also necessary to understand the nature of trance itself. ” (143-144)

“Masks seem exotic when you first learn about them, but to my mind Mask acting is no stranger than any other kind: no more weird than the fact that an actor can blush when his character is embarrassed, or turn white with fear, or that a cold will stop for the duration of the performance, and then start streaming again as soon as the curtain falls…Actors can be possessed by the characters they play just as they can be possessed by Masks…We find the the Mask strange because we don’t understand how irrational our responses to the face are anyway, we don’t realize that much of our lives is spent in some sort of trance, i.e. absorbed. ” (148)

“The Mask…exhibited without its costume, and without film, or even a photograph of the Mask in use, we respond to it only as an aesthetic object. Many Masks are beautiful or striking, but that’s not the point. A Mask is a device for driving personality out of the body and allowing spirit to take possession of it. A very beautiful Mask may be completely dead, while a piece of old sacking with a mouth and eye-holes torn in it may possess tremendous vitality. (149)

“Many actors report “split” states of consciousness, or amnesia; they speak of their body acting automatically. or as being inhabited by the character they are playing. Sybil Thorndike: “When you’re an actor you cease to be make and female, you’re a person with all the other persons inside you. (Great Acting, BBC Publications, 1967.) Edith Evans: “…I seem to have an awful lot of people inside me. Do you know what I mean? If I understand them I feel terribly like them when I am doing them…It’s quite odd you know. You are it, for quite a bit, and then you’re not.”

“In another kind of culture I think it’s clear that such actors could easily talk of being possessed by the character. It’s true that while some actors will maintain they always remain ‘themselves’ when they’re acting, but how do they know? Improvisers who maintain that they’re in a normal state of consciousness when they improvise often have unexpected gaps in their memories which only emerge when you question them closely….Normally we only know of our trance states by the time jumps. When an improviser feels that two hours have passed in twenty minutes, we’re entitled to ask where he was for the missing hour and forty minutes. ” (152)

“Most people only recognize “trance” when the subject looks confused–out of touch with the reality around him…I remember an experiment in which deep trance subjects were first asked how many objects there had been in the waiting-room. When they were put into trance and asked again, it was found they had actually observed more than ten times the number of objects than they had consciously remembered.” (153)