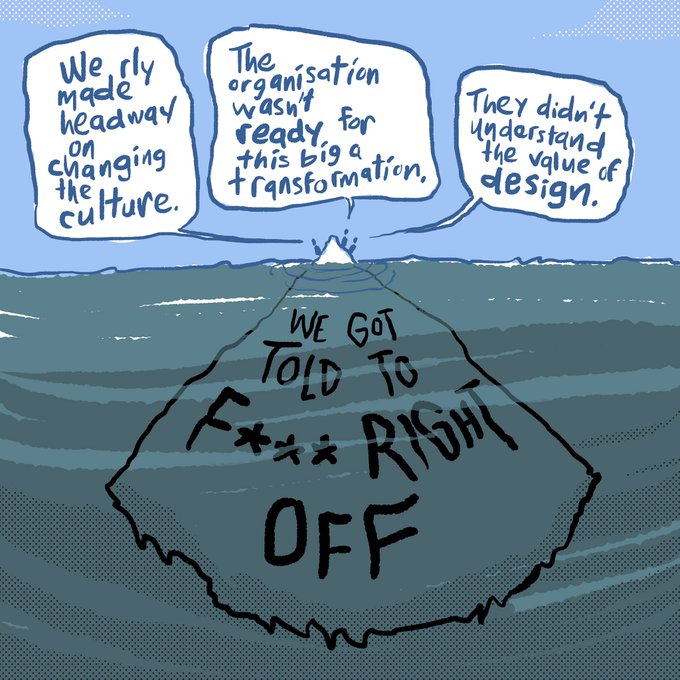

We Got Told to F*** Right Off

William S. Burroughs, the iconic writer of the Beat Generation, has been celebrated for his innovative and experimental approach to writing. In his work, Burroughs takes over all the markers of modernism, including structural fragmentation, parody, and pastiche. However, what he leaves out is the imperative to provide a replacement for the lost orders of the past. Burroughs does not care about original narratives or self-consciously artificial myth narratives that retain the imperative of progress, the free realization of human potential, or the emancipation of the oppressed. Tradition as an emancipatory project has played itself out in his work.

Burroughs’ writing is characterized by a lack of concern for traditional narrative structures and linear plotlines. Instead, he relies on techniques such as cut-up and collage to create a fragmented and disjointed narrative. This technique can be seen as a reflection of the fragmented nature of modern society, where traditional social orders have broken down, leaving individuals feeling disconnected and disoriented.

In addition to his use of structural fragmentation, Burroughs employs parody and pastiche, which involve the blending of high and low culture. By doing so, he undermines the traditional hierarchies that have long defined culture and society. This approach reflects the democratization of culture that occurred in the 20th century, where new forms of media, such as film and television, challenged the dominance of high culture.

However, despite his innovative and experimental approach to writing, Burroughs does not provide a replacement for the lost orders of the past. He does not offer a new narrative or myth that retains the imperative of progress, the free realization of human potential, or the emancipation of the oppressed. Instead, his work can be seen as a reflection of the postmodern condition, where the idea of progress and the possibility of a grand narrative have been rejected.

Tradition as an emancipatory project has played itself out in Burroughs’ work, and he offers no alternative to replace it. This approach can be seen as a reflection of the disillusionment and cynicism that characterized the post-World War II period, where the atrocities of war and the failures of the modernist project led many to question the possibility of progress.

In conclusion, William S. Burroughs’ innovative and experimental approach to writing is characterized by structural fragmentation, parody, and pastiche. However, he does not provide a replacement for the lost orders of the past or offer an alternative narrative or myth that retains the imperative of progress, the free realization of human potential, or the emancipation of the oppressed. His work reflects the postmodern condition, where the idea of progress and the possibility of a grand narrative have been rejected. Tradition as an emancipatory project has played itself out in his work, leaving the reader with a sense of disillusionment and cynicism.

In considering a potential replacement for postmodernism, it’s important to acknowledge the failure of modernist goals, such as resolving conflicts related to gender, class, and ethnicity, and achieving spiritual unity within society. It’s also crucial to recognize that attempts to regenerate myth as a centering structure have been unsuccessful. However, it’s not enough to simply reject mass politics, as advocated by thinkers like Jean-François Lyotard and Jean Baudrillard, because this approach remains complicit with capitalist structures and fails to offer a way out of the existing social order.

Instead, we need to look for someone who can produce new cultural values to replace those that have been bankrupted by postmodernism. William S. Burroughs is a prime example of an artist who can anticipate and leverage the work of theorists like Deleuze to create something new. While other authors like Pynchon, Heller, and Vonnegut can also offer valuable insights, Burroughs stands out as a particularly compelling figure.

By engaging with Burroughs’s work, we can move beyond the liminal space of literature and begin to develop a “plan of living” that goes beyond mere games. Through his innovative approach to writing and his willingness to embrace new forms of cultural production, Burroughs can offer us a way to move beyond the failures of postmodernism and toward a more meaningful and sustainable future.

He does not fit into a tidy category already subordinated to the larger scheme of Game A/the Mayan Scheme because he’s trying to find an escape route from the control systems of capital, subjectivity and language transforming individuals into mirror image of their controllers. “He examines the reversibility of hostile social relations and the symmetry of opposed political factions, and he articulates his theory that language, which is a virus that uses the human body as a host, constitutes the most powerful form of control. Burroughs cannot see a form of revolutionary practice to counter Game A’s dialectic, which liquidates the singularity of the individual as well as the connections of community in order to produce the false universality of profit. “Money eats quality and shits out quantity” His attempts can be understood as a systematic and sophisticated attempt to evade this dialectic, resembling Deleuze and focusing on a language within language’ that tends towards a language that marks the end of language as such.

Burroughs was known for his avant-garde writing style, which often involved cut-up and fold-in techniques, a method of rearranging words and phrases to create new meaning. He saw language as a tool for control and manipulation, with the power to shape individuals and societies to fit the desires of those in power. In his book “The Ticket That Exploded,” he writes, “All control systems are based on communication, and no communication is possible without a language.”

Burroughs’ rejection of the dominant societal and cultural norms of his time led him to experiment with various forms of artistic expression, including literature, film, and visual art. His work often explored themes of sexuality, addiction, and the nature of power and control. He saw these as fundamental issues in modern society, ones that needed to be addressed in order for true social change to occur.

In his writings, Burroughs often criticized the commercialization of art and culture, seeing it as a form of control and manipulation by the capitalist elite. He believed that art and culture should be free from the constraints of profit and used to inspire and liberate individuals and communities.

Burroughs’ emphasis on the power of language and its role in control and manipulation can be seen as a precursor to the postmodern critique of language and its relationship to power. His rejection of the dominant cultural norms and his experimentation with various forms of artistic expression can also be seen as a rejection of the modernist belief in progress and the linear development of culture.

In conclusion, William Burroughs’ work can be seen as an attempt to find an escape route from the control systems of capital, subjectivity, and language. His rejection of the dominant societal and cultural norms of his time, his experimentation with various forms of artistic expression, and his emphasis on the power of language and its role in control and manipulation all contributed to his unique perspective and legacy as an artist and thinker. While he may not fit neatly into a specific category or movement, his ideas and writings continue to inspire and challenge readers to question the status quo and imagine new possibilities for social change.

As he attempts to find an escape from the control systems of capital, subjectivity, and language that transform individuals into mirror images of their controllers. He examines the reversibility of hostile social relations and the symmetry of opposed political factions and believes that language, which he calls a virus, uses the human body as a host and constitutes the most powerful form of control. Burroughs attempts to evade this dialectic by focusing on a “language within language” that tends towards a language that marks the end of language as such, similar to Deleuze.

According to Burroughs, “Nothing is True, Everything is Permitted.” This means that if something is true, then something else must be maligned and prohibited by the Law as false. But if there is no essential truth, then there can be no prohibition. Burroughs believes in the literal realization of art, which requires the destruction of art as a mirror to nature and life. Art is a potentiality because it does not find its proof outside itself through a process of truthful representation but within itself.

Burroughs uses the detective novel and science fiction to displace structures of thought and transcendent structures of power. His work, like Deleuze’s, is utopian, but not in the same way as modernists. They do not rely on the truth or modernist myth but on the fluid mechanisms of desire in fantasy for their utopian drive.

Criticism of Burroughs has been mainly moral criticism directed at his referents in “real life,” rather than his work as writing. His life and his work have been held up to explicit or implicit moral standards and judged wanting. Burroughs submits the stereotypes of patriarchy to direct satire by revealing their subordination to the system of modern capitalism and its tool, the state. He acknowledges the “incompatible conditions of existence” of men and women and envisions an evolutionary step that would involve changes inconceivable from our POV, involving sexes fusing into one organism.

Burroughs adopts various elements of modernism such as structural fragmentation, parody and pastiche, and the mixing of high and low culture. However, he does not aim to replace the lost orders of the past with new narratives or mythologies that emphasize progress, human potential, or the liberation of the oppressed. The tradition as an emancipatory project has lost its efficacy and can no longer legitimize the production of novelty.

This shift from traditional to technological culture is a logical substitution of structures. According to Bruno Latour, ethnographers can combine myths, genealogies, politics, techniques, religions, epics, and rites into a single monograph for non-modern cultures. However, this is impossible for modern cultures due to the lack of analytic continuity in our fragmented fabric.

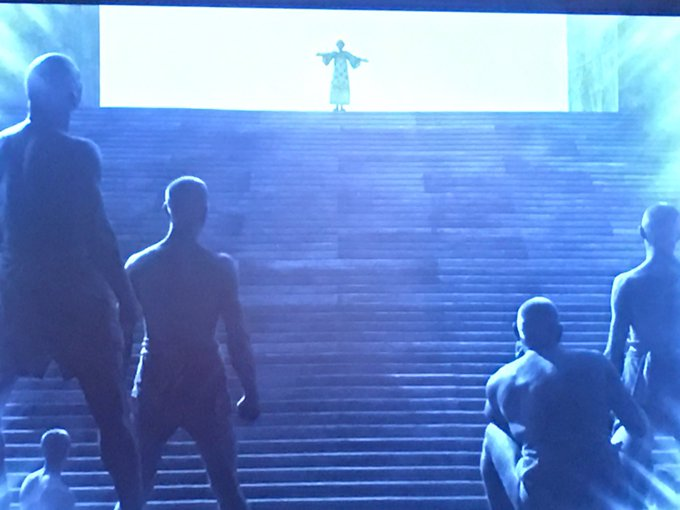

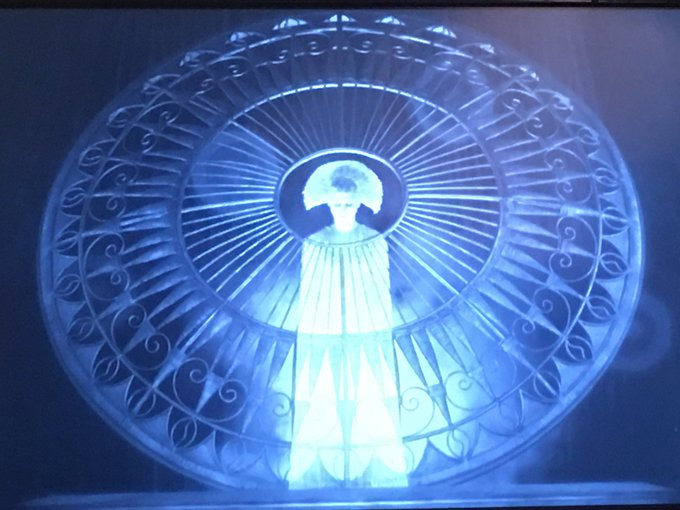

The Tower of Babel sequence in Metropolis is delivered by Maria during a sermon to the workers in the underground factory.

In this sequence, Maria uses the story of the Tower of Babel to inspire the workers to rise up against their oppressors and to come together in unity. She tells the story of how the people of Babel tried to build a tower to reach the heavens, but their arrogance and desire for power led to their downfall. The story serves as a cautionary tale about the dangers of unchecked ambition and the consequences of hubris.

As Maria delivers her sermon, the scene cuts to images of the city’s elite, who are shown plotting to maintain their power and control over the workers. The contrast between the opulence and luxury of the city’s elite and the squalor and poverty of the workers in the underground factory is stark.

The Babel sequence in Fritz Lang’s Metropolis explores the division between the “Head” that conceptualizes the glorious tower and the “Hands” that are recruited to build it. Unlike in Genesis, where the same men propose and construct Babel, an immediate rift is established in Metropolis. The sequence is visually captivating, with a crystalline focus on the images that is evocative and overpowering. The geometry is clean, precise, yet still larger than life. Thematically, the sequence is rich and fascinating, exploring the division between Head and Hands and the need for a Heart to mediate between them. The tower itself has an elegant, focused beauty, winding stairways, and a conical form, a true tribute to humanity’s aspirations for divine transcendence. The novella, written by Thea Von Harbou between preproduction and release, also highlights the alienation of the builders from the actual purpose of the tower. The characters watching the sequence in Jacques Rivette’s Paris Belongs to Us belong to a secret society grappling with a right-wing conspiracy, possibly mocking their metaphysical presuppositions. The Tower of Babel sequence is a highlight of both films and a favorite of many in silent cinema.

The Tower of Babel sequence is a powerful moment in the film, serving as a metaphor for the struggle between the workers and the city’s elite. The workers are like the people of Babel, striving to rise up against the power structure that keeps them in subjugation. The city’s elite, meanwhile, are like the rulers of Babel, blinded by their desire for power and control.

In conclusion, the Tower of Babel sequence in Metropolis is a mesmerizing and powerful moment in the film, delivered by Maria during a sermon to the workers in the underground factory. It serves as a cautionary tale about the dangers of unchecked ambition and the consequences of hubris, and as a metaphor for the struggle between the workers and the city’s elite. Fritz Lang’s use of religious imagery and symbolism in this sequence adds depth and complexity to the film’s themes, making it a landmark in cinema history.