Edwin Turner | January 14, 2019 | 9 comments

HIERONYMUS & BOSCH

Paul Kirchner’s Hieronymus & Bosch collects over eighty comic strips that riff on the afterlife of a “shameless ne’er-do-well named Hieronymus” and his faithful wooden toy duck, Bosch. The hapless pair are trapped in Hell, the primary setting for most of the strips (although we do get a bit of heaven and earth thrown in here and there). Kirchner’s Hell is a paradise of goofy gags. The one-pagers in Hieronymus & Bosch cackle with burlesque energy, propelled by a simple plot: our hero Hieronymus tries to escape, fails, and tries again.

And what sins have damned poor Hieronymus to Hell? When we first meet the cloaked miscreant he’s passed out, drooling all over an altar, clearly having enjoyed too much communion wine. An annoyed bishop prods him awake and kicks him from the church doors and into the village, where he proceeds to sin his ass off. Kirchner’s Hieronymus doesn’t quite fit all of the seven deadly sins in this morning (those same sins that the historical Hieronymus Bosch captured so well in his famous table), but he comes pretty damn close. Notably, he steals his comrade Bosch–a toy duck–from some poor kid. The wages of sin are death though, and poor Hieronymus, in a fit of wacky wrath, slips in some shit, falls on his toy duck, and careens into death.

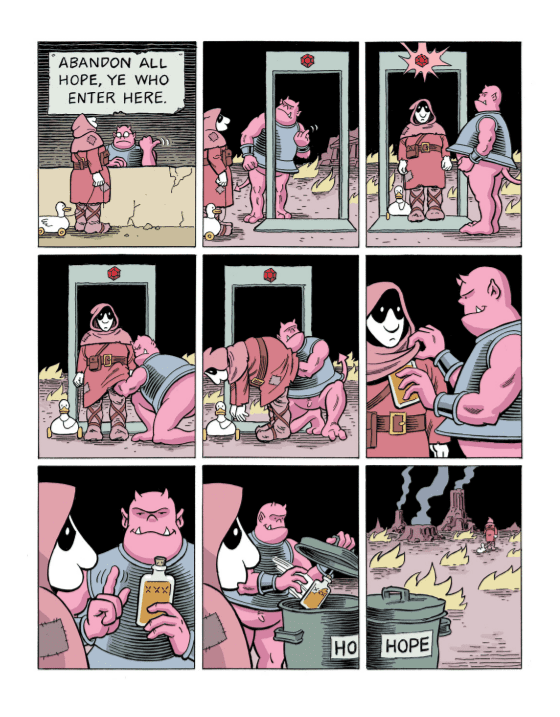

Bad news: He’s in Hell, where hope is strictly prohibited:

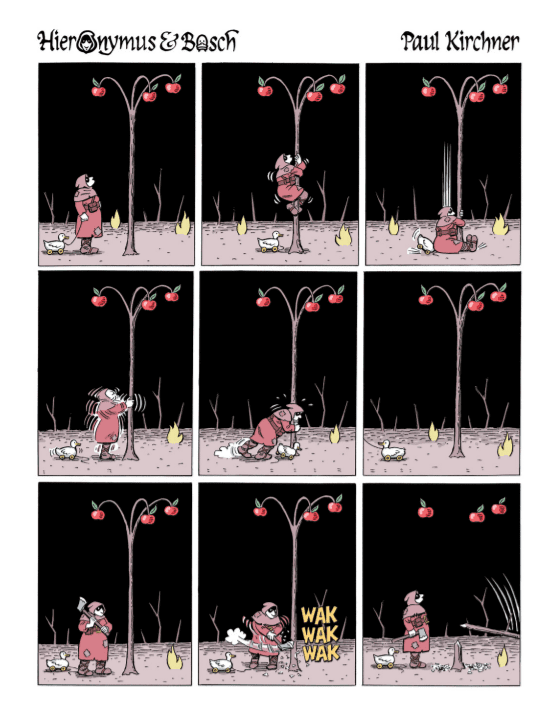

And yet there is hope in Hell. The set-up in almost every strip in Hieronymus & Bosch is predicated on hope: Hope of escape, yes, primarily, but also hope for a bit of reprieve, a touch of novelty, a brief moment of entertainment, a flash of human contact. Maybe just a juicy red apple.

But juicy red apples are hard to come by in Hell. The damned are far more likely to encounter shit and piss. Hieronymus & Bosch puts the scatology in eschatology. “People often talk about all the shit they have to put up with in life, so I figured that if they end up in Hell they will have to put up with a great deal more,” Kirchner writes in an essay on the genesis of his latest collection. He continues: “My Hell is less about torment than frustration, aggravation, and humiliation, and shit seemed a good way to depict that.”

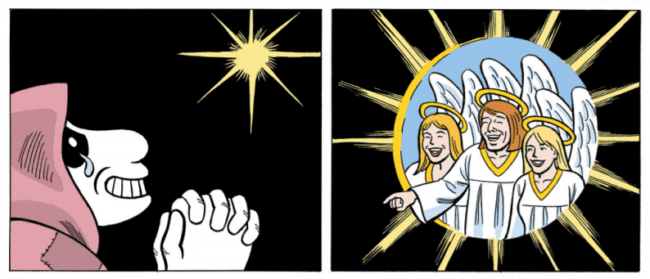

Kirchner’s Hell is full of shit: pools of it, moats of it, ice-cream cones full of it. And it’s not just the devils and demons that supply the excrement. No, even more insulting to Hell’s sorry denizens is the fact that they are literally being pissed and shat upon by the angels of Heaven above, a constant source of humiliation. If Kirchner’s vision of Hell is a space of abject indignation, his vision of Heaven is also colored by abjection. In Kirchner’s Heaven, schadenfreude is one of the greatest joys. The angels above are privy to all the punchlines below.

The demons of Kirchner’s Hell are downright sympathetic in comparison to these casually-cruel angels. Sure, the demons torture the damned souls, but they do so with a zany elan that almost comes across as loving. The demons are central to the Looney Tunes energy of Kirchner’s Hell. In each strip they foil our hero Hieronymus, out-tricking the would-be trickster in an eternal cycle of slapstick gags. And just like every other poor soul in Hell, the demons are just out there trying to have fun.

The demons get their jollies torturing Hieronymus and the other inhabitants of Hell by introducing something fun or entertaining to their prisoners, only to convert the potential pleasure into a degrading punishment. However, just as the demons torture the humans in Hell, they too are tortured by the Big Bad, Satan himself.

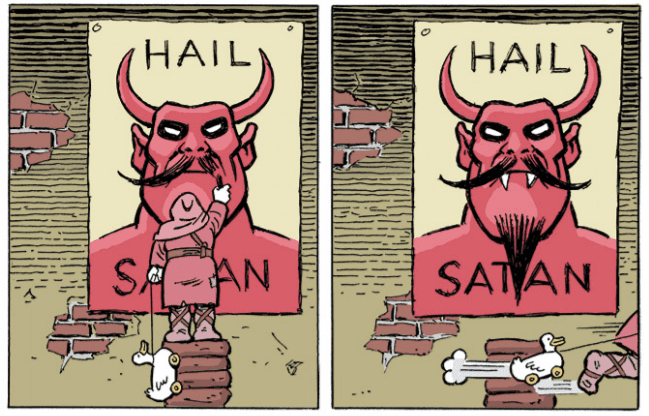

Satan is an intriguing figure in Hieronymus & Bosch, demonstrating a strangely perceptive ironic intelligence in the handful of strips in which he appears. He’s a creative figure, conjuring new tortures on the fly, and even with all his powers, he too is not immune to the degradation delivered from on high in Heaven. The last strip in the series is a masterstroke delivery of a classic slapstick punchline, but even if the joke is on Satan, Kirchner gives the Dark Lord the last word in Hieronymus & Bosch—quite literally. Satan authors the book’s postscript, an enthusiastic note delivered in the tone of an ebullient CEO bragging about his latest innovations. It’s all quite endearing. Indeed, one of my favorite moments in Kirchner’s strip happens when Satan sees that he’s been mocked. Some culprit (Hieronymus of course) has applied graffiti to the Satanic propaganda that decorates Hell. Instead of tracking down the guerrilla artist for additional tortures, Satan decides to keep the goatee and ‘stache.

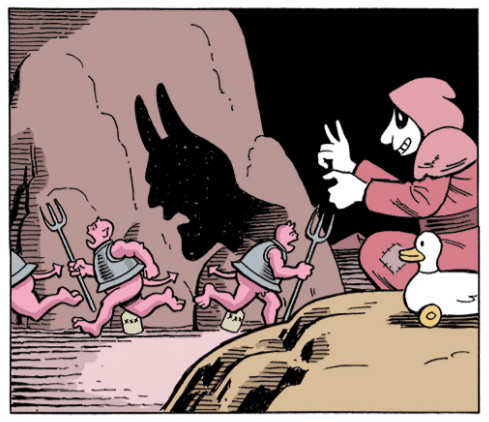

Hieronymus’s tactic in this little episode is typical of his main strategy of resistance. Like most tricksters, he’s an artist, and Hell is his creative space. Throughout the collection Hieronymus tries his hand at all sorts of creation: he writes, sculpts, paints, and even puts on a shadow puppet show. Creative action is a form of protest in Hieronymus & Bosch, and there’s an implicit argument here for Kirchner’s readers. Hieronymus might be damned, but at least he’s going to make something out of it and have a little fun.

So hapless Hieronymus tries to have a little fun in Hell, as do the demons, as does Satan. Kirchner’s Hell often erupts with circus energy: there are dance contests and merry-go-rounds, whack-a-moles and magic shows, Punch and Judy shows and carnivals. Of course, these amusements are always tricks—but at least someone’s having fun.

Appropriately, Hieronymus & Bosch has a fun visual style. The work here is a bit simpler than Kirchner’s early surreal Dope Rider strips, and rounder and softer than his bus strips. This isn’t to say that Hieronymus & Bosch doesn’t showcase Kirchner’s affection for surrealism and Escheresque drafting techniques–it does–but the strips in Hieronymus & Bosch show restraint in employing those moves. There’s a cartooniness to these strips that’s reminiscent of a less-frenetic Sergio Aragones or a less-grotesque Basil Wolverton. And while the collection employs occasional motifs from the painter Hieronymus Bosch, Kirchner is not overly-beholden to his strip’s namesake.

For all the simplicity of his design, Hieronymus himself is remarkably expressive. His frowns protest, his smiles plead, his grins show flashes of (momentary) triumph. He’s our human in Hell, and Kirchner imbues him with an heroic spirit, despite his loutish ways. Hieronymus exemplifies the human position as an artistic position, one which opposes the existential despair of living in a world of repetition and boredom. If life often seems boring, repetitive, and even meaningless, it’s up to us to convert boredom into fun, to find meaning in our own creative action. The gags and goofs in Hieronymus & Bosch illustrate that there can be fun in failure, that even if we fail we can get up and try, try again.