Let me tell you about the autumn I turned 13, when the world was opening up to me like a cracked egg, spilling out all its golden, chaotic possibilities. I was discovering Led Zeppelin—VOL IV spinning endlessly on my turntable, each track a revelation, each riff a gateway to some new dimension.

The music I was discovering at the time—Zeppelin, Tull, The Beatles—wasn’t just a collection of songs; it was a series of liminal spaces, thresholds to new ways of thinking and feeling. Zeppelin’s Physical Graffiti was a sprawling, chaotic masterpiece that refused to be pinned down, each track a doorway to some new sonic landscape.

Zeppelin, Tull, The Beatles—was not merely a collection of songs. No, it was something far more insidious, far more ideological. These albums functioned as liminal spaces, as thresholds into the Lacanian Real, where the symbolic order of my teenage existence was perpetually disrupted. Zeppelin’s Physical Graffiti was not just an album; it was a chaotic, sprawling objet petit a, a sonic embodiment of desire that always eluded my grasp, each track a failed attempt to articulate the ineffable. Tull’s Aqualung? A dialectical masterpiece, blurring the lines between rock and folk, between the sacred and the profane, forcing me to confront the inherent contradictions of my own burgeoning identity. And The Beatles’ White Album!—a kaleidoscopic rupture in the fabric of pop itself, a traumatic intrusion of the Real that shattered my naive belief in the stability of genre, of form, of meaning.

These albums were lines of flight, to borrow a term from Deleuze and Guattari. They were escapes from the mundane, the predictable, the safe. They were journeys into the unknown, into the spaces between genres, between cultures, between worlds. They were the sound of possibility, of freedom, of becoming.

They were also symptoms. Symptoms of a deeper cultural anxiety, of a desire to escape the suffocating confines of late capitalism’s commodified soundscape. They were attempts—always partial, always failing—to traverse the fantasy of mainstream rock and touch the void beyond. And yet, they succeeded precisely in their failure, in their inability to fully cohere, to fully mean. It was in their gaps, their contradictions, their excesses, that I found my own subjectivity reflected back at me, fractured and incomplete.

And then there was Iron Maiden, my gateway to metal, the band that had soundtracked my early teenage years with the galloping fury of The Number of the Beast, the intricate storytelling of Piece of Mind, and the epic grandeur of Powerslave. But by 1986, something was shifting.

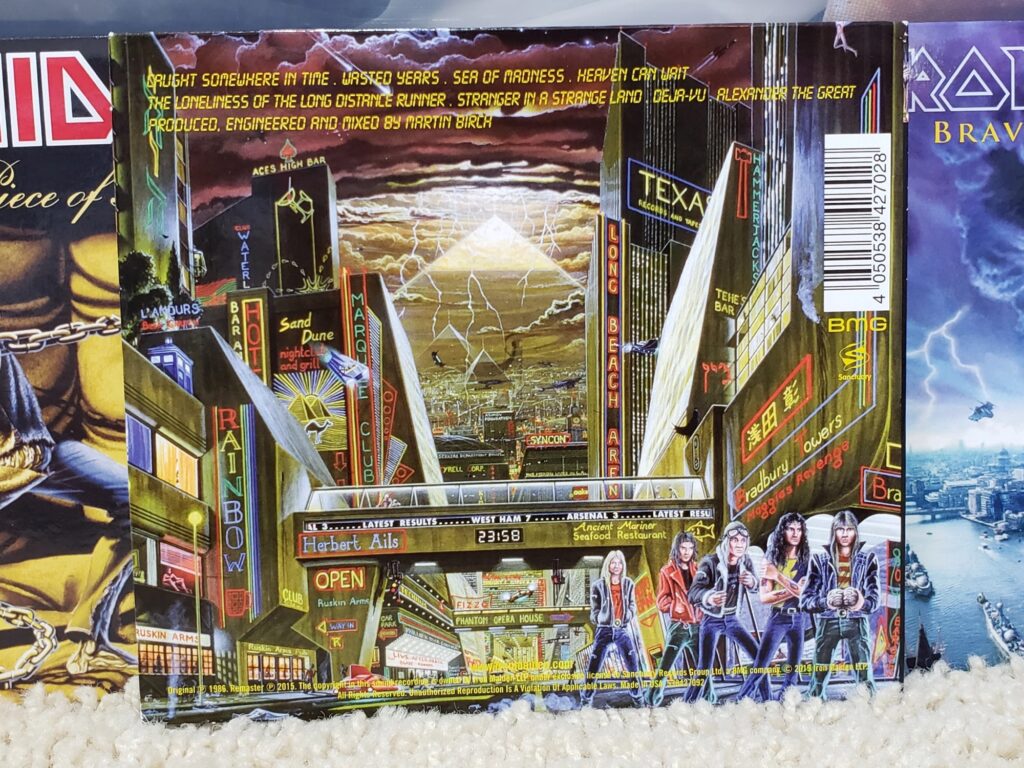

Somewhere in Time arrived, and I was ready to be blown away. Instead, I was… confused. The synths? The glossy production? The songs that felt like they were running in circles instead of charging forward? It wasn’t bad, per se—it was just… safe. Maiden had always been a band that pushed boundaries, but here they seemed content to stay within the lines they’d already drawn. “Wasted Years” was a solid single, sure, but where was the urgency, the danger, the edge? It felt like they were treading water, and I was too young to understand why a band might do that.

They seemed to have become something else entirely: not a line of flight, but a recuperation. These albums were not thresholds into the Real; they were walls, fortifications against it. They were the sound of a band that had retreated into the symbolic order, into the safety of formula, of repetition, of the same. The synths, the glossy production, the recycled riffs—these were not innovations; they were defenses, mechanisms to shield both the band and the listener from the traumatic void of creativity itself.

Then came Seventh Son of a Seventh Son in 1988, and I wanted to believe. The concept was ambitious, the artwork was killer, and the title track had moments of brilliance. But again, something was missing. The sharpness, the immediacy, the bite of their earlier work was dulled. It wasn’t that the album was bad—it was just that it felt like Maiden had settled into a formula, one that prioritized polish over passion. I was discovering bands like Zeppelin or the Who, who seemed to reinvent themselves with every album, and here was Maiden, my once-heroic metal gods, playing it safe. Somewhere in Time and Seventh Son of a Seventh Son were not lines of flight; they were cul-de-sacs, dead ends, the sound of a band that had run out of road.

It wasn’t just me, either. My friends felt it too. We’d argue over whether Bruce Dickinson’s voice was even better or if Steve Harris’s basslines were becoming predictable. We’d compare Seventh Son to Master of Puppets or Reign in Blood, albums that felt like they were pushing metal into new territories, and wonder why Maiden seemed content to stay in their lane.

It wasn’t just that the songs weren’t as sharp or as urgent as their earlier work; it was that they lacked the sense of adventure, the willingness to take risks, to push boundaries, to explore new territories. They were the sound of a band that had found a formula and decided to stick with it, even as the world around them was changing, even as their fans were growing up and discovering new sounds, new ideas, new possibilities.

And here we arrive at the crux of the matter: the true disappointment of these albums lies not in their failure to innovate, but in their success at avoiding failure. They were too polished, too coherent, too safe. They lacked the necessary antagonism, the necessary gap, through which the Real might erupt. They were, in short, ideological in the purest sense: they presented themselves as radical, as transgressive, while in fact reinforcing the very structures they claimed to challenge.

For a teenager on the cusp of adulthood, this was not merely disappointing; it was traumatic. It was a betrayal not just of my expectations, but of my very desire. I wanted Iron Maiden to be my guides into the Real, my companions in the struggle against the symbolic order. Instead, they became its agents, its enforcers. They chose the safety of the known over the danger of the unknown, the comfort of the formula over the terror of the void.

And maybe that’s the real disappointment of those albums: not that they were bad, but that they were safe. They were the sound of a band that had decided to stay within the limits, to play it safe, to stick with what they knew. And for a teenager on the cusp of adulthood, hungry for new experiences, new ideas, new ways of seeing the world, that was the ultimate betrayal.

So while I’ll always have a soft spot for The Number of the Beast and Powerslave, those later albums will always remind me of a time when the world was opening up to me, and Iron Maiden decided to stay behind.And so, while I will always retain a nostalgic attachment to The Number of the Beast and Powerslave, those later albums will forever stand as a reminder of a missed opportunity, of a failure to confront the Real. They are the sound of a band that looked into the abyss—and then promptly built a fence around it.

Looking back, I can see that Somewhere in Time and Seventh Son were transitional albums, the sound of a band trying to evolve without alienating their fanbase. But at 13, I didn’t have the patience for that. I wanted my heroes to be fearless, to take risks, to match the intensity of my own discoveries. Instead, Maiden felt like they were running out of sharp songs, content to coast on the formula they’d perfected years earlier.

And maybe that’s the curse of being a teenager: you want the world to keep up with your hunger, your curiosity, your need for something more. When it doesn’t, it feels like a betrayal. So while I’ll always have a soft spot for The Number of the Beast and Powerslave, those later albums will always remind me of a time when the world was opening up to me, and Iron Maiden decided to stay behind.